INFORMATION:

The paper, titled "Long-term Drying of Mars Caused by Sequestration of Ocean-scale Volumes of Water in the Crust," published in Science on 16 March 2021. This work was supported by a NASA Habitable Worlds award, a NASA Earth and Space Science Fellowship (NESSF) award, and a NASA Future Investigator in NASA Earth and Space Science and Technology (FINESST) award.

What happened to mars's water? It is still trapped there

New data challenges the long-held theory that all of Mars's water escaped into space

2021-03-16

(Press-News.org) Billions of years ago, the Red Planet was far more blue; according to evidence still found on the surface, abundant water flowed across Mars and forming pools, lakes, and deep oceans. The question, then, is where did all that water go?

The answer: nowhere. According to new research from Caltech and JPL, a significant portion of Mars's water--between 30 and 99 percent--is trapped within minerals in the planet's crust. The research challenges the current theory that the Red Planet's water escaped into space.

The Caltech/JPL team found that around four billion years ago, Mars was home to enough water to have covered the whole planet in an ocean about 100 to 1,500 meters deep; a volume roughly equivalent to half of Earth's Atlantic Ocean. But, by a billion years later, the planet was as dry as it is today. Previously, scientists seeking to explain what happened to the flowing water on Mars had suggested that it escaped into space, victim of Mars's low gravity. Though some water did indeed leave Mars this way, it now appears that such an escape cannot account for most of the water loss.

"Atmospheric escape doesn't fully explain the data that we have for how much water actually once existed on Mars," says Caltech PhD candidate Eva Scheller (MS '20), lead author of a paper on the research that was published by the journal Science on March 16 and presented the same day at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC). Scheller's co-authors are Bethany Ehlmann, professor of planetary science and associate director for the Keck Institute for Space Studies; Yuk Yung, professor of planetary science and JPL senior research scientist; Caltech graduate student Danica Adams; and Renyu Hu, JPL research scientist. Caltech manages JPL for NASA.

The team studied the quantity of water on Mars over time in all its forms (vapor, liquid, and ice) and the chemical composition of the planet's current atmosphere and crust through the analysis of meteorites as well as using data provided by Mars rovers and orbiters, looking in particular at the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen (D/H).

Water is made up of hydrogen and oxygen: H2O. Not all hydrogen atoms are created equal, however. There are two stable isotopes of hydrogen. The vast majority of hydrogen atoms have just one proton within the atomic nucleus, while a tiny fraction (about 0.02 percent) exist as deuterium, or so-called "heavy" hydrogen, which has a proton and a neutron in the nucleus.

The lighter-weight hydrogen (also known as protium) has an easier time escaping the planet's gravity into space than its heavier counterpart. Because of this, the escape of a planet's water via the upper atmosphere would leave a telltale signature on the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen in the planet's atmosphere: there would be an outsized portion of deuterium left behind.

However, the loss of water solely through the atmosphere cannot explain both the observed deuterium to hydrogen signal in the Martian atmosphere and large amounts of water in the past. Instead, the study proposes that a combination of two mechanisms--the trapping of water in minerals in the planet's crust and the loss of water to the atmosphere--can explain the observed deuterium-to-hydrogen signal within the Martian atmosphere.

When water interacts with rock, chemical weathering forms clays and other hydrous minerals that contain water as part of their mineral structure. This process occurs on Earth as well as on Mars. Because Earth is tectonically active, old crust continually melts into the mantle and forms new crust at plate boundaries, recycling water and other molecules back into the atmosphere through volcanism. Mars, however, is mostly tectonically inactive, and so the "drying" of the surface, once it occurs, is permanent.

"Atmospheric escape clearly had a role in water loss, but findings from the last decade of Mars missions have pointed to the fact that there was this huge reservoir of ancient hydrated minerals whose formation certainly decreased water availability over time," says Ehlmann.

"All of this water was sequestered fairly early on, and then never cycled back out," Scheller says. The research, which relied on data from meteorites, telescopes, satellite observations, and samples analyzed by rovers on Mars, illustrates the importance of having multiple ways of probing the Red Planet, she says.

Ehlmann, Hu, and Yung previously collaborated on research that seeks to understand the habitability of Mars by tracing the history of carbon, since carbon dioxide is the principal constituent of the atmosphere. Next, the team plans to continue to use isotopic and mineral composition data to determine the fate of nitrogen and sulfur-bearing minerals. In addition, Scheller plans to continue examining the processes by which Mars's surface water was lost to the crust using laboratory experiments that simulate Martian weathering processes, as well as through observations of ancient crust by the Perseverance rover. Scheller and Ehlmann will also aid in Mars 2020 operations to collect rock samples for return to Earth that will allow the researchers and their colleagues to test these hypotheses about the drivers of climate change on Mars.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Going back in time restores decades of quiet corn drama

2021-03-16

URBANA, Ill. - Corn didn't start out as the powerhouse crop it is today. No, for most of the thousands of years it was undergoing domestication and improvement, corn grew humbly within the limits of what the environment and smallholder farmers could provide.

For its fertilizer needs, early corn made friends with nitrogen-fixing soil microbes by leaking an enticing sugary cocktail from its roots. The genetic recipe for this cocktail was handed down from parent to offspring to ensure just the right microbes came out to play.

But then the Green Revolution changed everything. Breeding tools improved dramatically, leading to faster-growing, higher-yielding hybrids than the world had ...

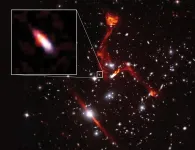

Image release: Cosmic lens reveals faint radio galaxy

2021-03-16

Radio telescopes are the world's most sensitive radio receivers, capable of finding extremely faint wisps of radio emission coming from objects at the farthest reaches of the universe. Recently, a team of astronomers used the National Science Foundation's Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) to take advantage of a helping hand from nature to detect a distant galaxy that likely is the faintest radio-emitting object yet found.

The discovery was part of the VLA Frontier Fields Legacy Survey, led by NRAO Astronomer Eric Murphy, which used distant clusters of galaxies as natural lenses ...

Tired at the office? Take a quick break; your work will benefit

2021-03-16

Recent research shows that people are more likely to take "microbreaks" at work on days when they're tired - but that's not a bad thing. The researchers found microbreaks seem to help tired employees bounce back from their morning fatigue and engage with their work better over the course of the day.

At issue are microbreaks, which are short, voluntary and impromptu respites in the workday. Microbreaks include discretionary activities such as having a snack, chatting with a colleague, stretching or working on a crossword puzzle.

"A microbreak is, by definition, short," says Sophia Cho, co-author of a paper on the work and an assistant professor ...

Army, Air Force fund research to pursue quantum computing

2021-03-16

RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. -- Joint Army- and Air Force-funded researchers have taken a step toward building a fault-tolerant quantum computer, which could provide enhanced data processing capabilities.

Quantum computing has the potential to deliver new computing capabilities for how the Army plans to fight and win in what it calls multi-domain operations. It may also advance materials discovery, artificial intelligence, biochemical engineering and many other disciplines needed for the future military; however, because qubits, the fundamental building blocks of quantum computers, are intrinsically fragile, a longstanding barrier to quantum computing has been effective implementation of quantum error correction.

Researchers at University of Massachusetts Amherst, ...

Standing out from the crowd

2021-03-16

Corporate strategies should be as unique as possible, in fact highly specific to each individual company. This enables companies to compete successfully in the long term. However, the capital market and others, including analysts, often react negatively to the idea of unique strategies. The reason is that deviating from typical industry standards makes them more complex to evaluate. This regularly discourages companies from focusing on unique strategies, even though they would be beneficial for the company in the long term. This contradiction is known as the "uniqueness paradox". A research team from the Universities of Göttingen and Groningen has investigated the influence of different types of investors on the extent of the paradox and thus on the choice of unique strategies. The results ...

Could birth control pills ease concussion symptoms in female athletes?

2021-03-16

Higher progesterone level is protective in mild traumatic brain injury

Blood flow in brain is linked to progesterone and stress symptom levels

Most concussion research has been focused on male athletes

CHICAGO --- Could birth control pills help young female athletes recover faster from concussions and reduce their symptoms?

A new Northwestern Medicine pilot study has shown when a female athlete has a concussion injury during the phase of her menstrual cycle when progesterone is highest, she feels less stress. Feeling stressed is one symptom of a concussion. Feeling less stressed is a marker of recovery.

The study also revealed for the first time the physiological reason for the neural protection is increased ...

Leaders take note: Feeling powerful can have a hidden toll

2021-03-16

New research from the University of Florida Warrington College of Business finds that feeling psychologically powerful makes leaders' jobs seem more demanding. And perceptions of heightened job demands both help and hurt powerful leaders.

Trevor Foulk of the University of Maryland Robert H. Smith School of Business and Klodiana Lanaj, Martin L. Schaffel Professor at UF, note that while power-induced job demands are key to helping leaders more effectively pursue their goals and feel that their jobs are meaningful each day at work, these demands can also cause pain and discomfort, felt in the evening at home.

"Power is generally considered a desirable thing, as leaders often seek power, and it's very rare for leaders to turn powerful roles down," Foulk said. "However, this view is qualified ...

Controlling sloshing motions in sea-based fish farming cages improves fish welfare

2021-03-16

WASHINGTON, March 16, 2021 -- Sea-based fish farming systems using net pens are hard on the environment and the fish. A closed cage can improve fish welfare, but fresh seawater must be continuously circulated through the cage. However, ocean waves can cause this circulating water to slosh inside the cage, creating violent motions and endangering the cage and the fish.

A study using a scale-model fish containment system is reported in Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing. The study shows why violent sloshing motions arise and how to minimize them.

Gentle currents can be artificially maintained inside cylindrical closed cages developed for salmon farming. The current is produced by injecting seawater through ...

Second COVID-19 wave in Europe less lethal than first wave

2021-03-16

WASHINGTON, March 16, 2021 -- As Europe experienced its enormous second wave of the COVID-19 disease, researchers noticed the mortality rate -- progression from cases to deaths -- was much lower than during the first wave.

This inspired researchers from the University of Sydney and Tsinghua University to study and quantify the mortality rate on a country-by-country basis to determine how much the mortality rate from the second wave decreased from the first.

In Chaos, by AIP Publishing, Nick James, Max Menzies, and Peter Radchenko introduce methods to study the progression of COVID-19 cases to deaths during the pandemic's different waves. Their methods involve applied mathematics, specifically nonlinear dynamics, and time series analysis.

"We take a time series, ...

Crying human tear glands grown in the lab

2021-03-16

Researchers from the lab of Hans Clevers (Hubrecht Institute) and the UMC Utrecht used organoid technology to grow miniature human tear glands that actually cry. The organoids serve as a model to study how certain cells in the human tear gland produce tears or fail to do so. Scientists everywhere can use the model to identify new treatment options for patients with tear gland disorders, such as dry eye disease. Hopefully in the future, the organoids can even be transplanted into patients with non-functioning tear glands. The results will be published in Cell Stem Cell on the 16th of March.

The tear gland is located in the upper part of the eye socket. It secretes tear fluid, which is essential for lubrication and nutrition of the cornea and has antibacterial components. Rachel Kalmann ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

New discovery of younger Ediacaran biota

Lymphovenous bypass: Potential surgical treatment for Alzheimer's disease?

When safety starts with a text message

CSIC develops an antibody that protects immune system cells in vitro from a dangerous hospital-acquired bacterium

New study challenges assumptions behind Africa’s Green Revolution efforts and calls for farmer-centered development models

Immune cells link lactation to long-lasting health

Evolution: Ancient mosquitoes developed a taste for early hominins

Pickleball players’ reported use of protective eyewear

Changes in organ donation after circulatory death in the US

Fertility preservation in people with cancer

[Press-News.org] What happened to mars's water? It is still trapped thereNew data challenges the long-held theory that all of Mars's water escaped into space