Jupiter's "dawn storm" auroras are surprisingly Earth-like

A new study tracks the life cycle of the spectacular ultraviolet storms in the big planet's aurora, generated by charged particles from its volcanic moon, Io

2021-03-16

(Press-News.org) The storms, which consist of brightenings and broadenings of the dawn flank of an oval of auroral activity that encircles Jupiter's poles, evolve in a pattern surprisingly reminiscent of familiar surges in the aurora that undulate across Earth's polar skies, called auroral substorms, according to the authors.

The new study is the first to track the storms from their birth on the nightside of the giant planet through their full evolution. It was published today in AGU Advances, AGU's journal for high-impact, short-format reports with immediate implications spanning all Earth and space sciences.

During a dawn storm, Jupiter's quiet and regular auroral arc transforms into a complex and intensely bright auroral feature. It emits hundreds to thousands of Gigawatts of ultraviolet light into space as it rotates from the night side to the dawn side and ultimately to the day side of the planet over the course of 5-10 hours. A Gigawatt is the power produced by a typical modern nuclear reactor. This colossal brightness implies that at least ten times more energy was transferred from the magnetosphere to the upper atmosphere of Jupiter.

Previously, dawn storms had only been observed from ground-based telescopes on Earth or the Hubble Space Telescope, which can only offer side views of the aurora and cannot see the night side of the planet. Juno revolves around Jupiter every 53 days along a highly elongated orbit that brings it right above the poles every orbit.

"This is a real game changer," said Bertrand Bonfond, a researcher from the University of Liège and lead author of the new study. "We finally got to find out what was happening on the night side, where the dawn storms are born."

Familiar auroral sequences, different engines

Polar auroras on Earth and on Jupiter are images of processes occurring in the magnetic fields that surround them. Both planets generate magnetic fields that capture charged particles.

Earth's magnetosphere is shaped by charged particles flowing out of the sun called the solar wind. Bursts of solar wind stretch Earth's magnetic field into a long tail on the nightside of the planet. When that tail snaps back, it fires charged particles into the nightside ionosphere, which appear as spectacular auroral light shows.

The new study found the timing of the dawn storms on Jupiter did not correlate with solar wind fluctuations. Jupiter's magnetosphere is mostly populated by particles escaping from its volcanic moon Io, which then get ionized and trapped around the planet by its magnetic field.

The sources of mass and energy fundamentally differ between these two magnetospheres, leading to auroras that usually look quite different. However, the dawn storms, as unraveled by Juno's ultraviolet spectrograph, looked familiar to the researchers.

"When we looked at the whole dawn storm sequence, we couldn't help but notice that the dawn storm auroras at Jupiter are very similar to a type of terrestrial auroras called substorms" said Zhonghua Yao, co-author of the study and scientific collaborator at the University of Liège.

The substorms result from the explosive reconfiguration of the tail of the magnetosphere. On Earth, they are strongly related to the variations of the solar wind and of the orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field. On Jupiter, such explosive reconfigurations are rather related to an overspill of the plasma originating from Io.

These findings demonstrate that, whatever their sources, particles and energy do not always circulate smoothly in planetary magnetospheres. They often accumulate until the magnetospheres collapse and generate substorm-like responses in the planetary aurorae.

"Even if their engine is different, showing for the first time the link between these two very different systems allows us to identify the universal phenomena from the peculiarities specific to each planet," Bonfond said.

INFORMATION:

Authors:

Bertrand Bonfond, corresponding author, (Université de Liège)

Zhonghua Yao (Chinese Academy of Sciences)

Randy Gladstone (Southwest Research Institute)

Denis Grodent (University of Liège)

Jean-Claude Gérard (Université de Liège)

Jessy Matar (University of Liège)

Benjamin Palmaerts (LPAP, University of Liege)

Thomas Greathouse (Southwest Research Institute)

Vincent Hue (Southwest Research Institute)

Maarten Versteeg (Southwest Research Institute)

Joshua Kammer (SWRI)

Rohini Giles (Southwest Research Institute)

Chihiro Tao (National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT))

Marissa Vogt (Boston University)

Alessandro Mura (INAF-IAPS)

Alberto Adriani (IAPS-INAF)

William Kurth (University of Iowa)

Barry Mauk (Johns Hopkins University)

Scott Bolton (Southwest Research Institute)

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-16

The market for air purifiers is booming, but a new study has found that some air cleaning technologies marketed for COVID-19 may be ineffective and have unintended health consequences.

The study, authored by researchers at Illinois Tech, Portland State University, and Colorado State University, found that cleaning up one harmful air pollutant can create a suite of others.

Both chamber and field tests found that an ionizing device led to a decrease in some volatile organic compounds (VOCs) including xylenes, but an increase in others, most prominently oxygenated VOCs (e.g., acetone, ethanol) and toluene, substances commonly found in paints, ...

2021-03-16

Those who have persistent trouble sleeping may have an especially difficult grieving process after the death of a loved one, a new study co-authored by a University of Arizona researcher finds.

Most people who lose a close friend or family member will experience sleep troubles as part of the grieving process, as the body and mind react to the stress of the event, said study co-author Mary-Frances O'Connor, a professor in the UArizona Department of Psychology.

But O'Connor and her collaborators found that those who had persistent sleep challenges before losing someone were at higher risk for developing complicated grief after a loss. Complicated grief is characterized by a yearning for a lost loved one ...

2021-03-16

It would surprise no one that pursuing a graduate degree can be a stressful endeavor, and for students who are transgender and nonbinary (TNB), the atmosphere can become toxic, according to University of Houston researcher Nathan Grant Smith. In a new paper published in Higher Education, Smith provides an analysis of current literature pertaining to TNB graduate student experiences and suggests interventions in graduate education to create more supportive environments for TNB students.

"Nearly 50% of graduate students report experiencing emotional or psychological distress during their enrollment in graduate school. Levels of distress are particularly high for transgender ...

2021-03-16

It has long been understood that a parent's DNA is the principal determinant of health and disease in offspring. Yet inheritance via DNA is only part of the story; a father's lifestyle such as diet, being overweight and stress levels have been linked to health consequences for his offspring. This occurs through the epigenome - heritable biochemical marks associated with the DNA and proteins that bind it. But how the information is transmitted at fertilization along with the exact mechanisms and molecules in sperm that are involved in this process has been unclear until now.

A new study from McGill, published recently in Developmental Cell, has made a significant advance in the field by identifying how environmental information is transmitted by ...

2021-03-16

Lightning strikes -- perhaps a quintillion of them, occurring over a billion years -- may have provided sparks of life for the early Earth.

A new study by researchers at Yale and the University of Leeds contends that over time, these bolts from the blue unlocked the phosphorus necessary for the creation of biomolecules that would be the basis of life on the planet.

"This work helps us understand how life may have formed on Earth and how it could still be forming on other, Earth-like planets," said lead author Benjamin Hess, a graduate student in Yale's Department of Earth & Planetary ...

2021-03-16

Lightning strikes were just as important as meteorites in creating the perfect conditions for life to emerge on Earth, geologists say.

Minerals delivered to Earth in meteorites more than 4 billion years ago have long been advocated as key ingredients for the development of life on our planet.

Scientists believed minimal amounts of these minerals were also brought to early Earth through billions of lightning strikes.

But now researchers from the University of Leeds have established that lightning strikes were just as significant as meteorites in performing this essential function and allowing life to manifest.

They say this shows that life could develop on Earth-like planets through the same mechanism at any time if atmospheric conditions are right. The research ...

2021-03-16

The activity of enzymes in industrial processes, laboratories, and living beings can be remotely controlled using light. This requires their immobilization on the surface of nanoparticles and irradiation with a laser. Near-infrared light can penetrate living tissue without damaging it. The nanoparticles absorb the energy of the radiation and release it back in the form of heat or electronic effects, triggering or intensifying the enzymes' catalytic activity. This configures a new field of study known as plasmonic biocatalysis.

Research conducted at the University of São Paulo's Chemistry Institute (IQ-USP) in Brazil investigated the activity of enzymes immobilized on gold ...

2021-03-16

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. -- March 16, 2021 -- The findings of a recent analysis conducted by the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), an affiliate of City of Hope, suggest that ecosystems suitable for harboring ticks that carry debilitating Lyme disease could be more widespread than previously thought in California, Oregon and Washington.

Bolstering the research were the efforts of an army of "citizen scientists" who collected and submitted 18,881 ticks over nearly three years through the Free Tick Testing Program created by the Bay Area Lyme Foundation, which funded the research, producing a wealth of data for scientists to analyze.

This new study builds on initial research led by the ...

2021-03-16

March 16, 2021, Mountain View, CA - In a comment published today in Nature Astronomy, Dr. Nathalie Cabrol, Director of the Carl Sagan Center for Research at the SETI Institute, challenges assumptions about the possibility of modern life on Mars held by many in the scientific community.

As the Perseverance rover embarks on a journey to seek signs of ancient life in the 3.7 billion years old Jezero crater, Cabrol theorizes that not only life could still be present on Mars today, but it could also be much more widespread and accessible than previously believed. Her conclusions are based on years of exploration of early Mars analogs in extreme environments in the Chilean altiplano and the Andes funded ...

2021-03-16

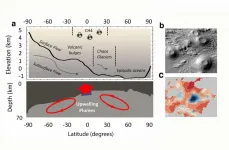

Billions of years ago, the Red Planet was far more blue; according to evidence still found on the surface, abundant water flowed across Mars and forming pools, lakes, and deep oceans. The question, then, is where did all that water go?

The answer: nowhere. According to new research from Caltech and JPL, a significant portion of Mars's water--between 30 and 99 percent--is trapped within minerals in the planet's crust. The research challenges the current theory that the Red Planet's water escaped into space.

The Caltech/JPL team found that around four billion years ago, Mars was home to enough water to have covered the whole planet in an ocean about 100 to 1,500 meters deep; a volume roughly ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Jupiter's "dawn storm" auroras are surprisingly Earth-like

A new study tracks the life cycle of the spectacular ultraviolet storms in the big planet's aurora, generated by charged particles from its volcanic moon, Io