(Press-News.org) Scientists have witnessed bonobo apes adopting infants who were born outside of their social group for the first time in the wild.

Researchers, including psychologists at Durham University, UK, twice saw the unusual occurrence among bonobos in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in central Africa.

They say their findings give us greater insight into the parental instincts of one of humans' closest relatives and could help to explain the emotional reason behind why people readily adopt children who they have had no previous connection with.

The research, led by Kyoto University, in Japan, is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Researchers observed a number of bonobo groups over several years in the Wamba area of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The examples of cross-group adoption were seen between April 2019 and March 2020 before Covid-19 restrictions brought observations to a temporary halt.

Chio, aged between 52 to 57 years old, who is thought to be post-menopausal, was seen to adopt three-year-old Ruby who had been part of another unknown group.

Marie, an 18-year-old bonobo was also seen to adopt Flora, who is estimated to be two-and-a-half-years-old, after Flora's mother disappeared from a separate group.

Neither Chio nor Marie, who had already had their own offspring, had any pre-existing family connections to the adopted infants or any strong social connections with the youngsters' biological mothers, yet both readily adopted the young bonobos.

Both adoptive mothers carried, groomed, nursed, and shared food with their adopted young. Ruby and Flora were also both observed suckling at their adopted mothers. In the case of Ruby, she might have been suckling for comfort as Chio is unlikely to have been producing milk.

The researchers say this caring nature is evidence of bonobos' strong attraction to infants and high tolerance of individuals, including immature youngsters, from outside of their normal group.

Bonobos, along with chimpanzees, are humans' closest relatives and the researchers say their discovery helps us to understand adoption among people.

Marie-Laure Poiret, a PhD Research Student, in the Department of Psychology, at Durham University, UK, said: "Usually in wild animals adoptive mothers are related to orphaned infants or sometimes young females will adopt orphans to improve their own care-giving behaviours, which increases the future survival chances of their own offspring.

"This means that adoption in non-human animals can usually be explained by the adoptive mother's own self-interest or pre-existing social relationships.

"The cross-group adoption we have seen in the cases of both Chio and Ruby, and Marie and Flora, is as surprising as it is wonderful and perhaps helps us explain adoption among humans, which cannot be explained purely by the benefits received by adoptive mothers.

"Instead it is fair to say from the examples we have seen in bonobos that adoption in humans can be explained by a selfless concern for others and an emotional desire to offer care to someone who we have no previous connection with."

The bonobo groups included in this study have been observed by scientists since the 1970s and researchers have come to know the individuals in each of the groups.

Research lead author Nahoko Tokuyama, Assistant Professor in the Primate Research Institute and Wildlife Research Centre at Kyoto University, Japan, who has spent more than ten years studying bonobos in the Democratic Republic of Congo, said bonobos "never ceased to amaze".

Dr Tokuyama added: "Although cases of adoption were observed in non-human primates, the adoptive mother and adoptees almost exclusively belonged to the same social group.

"This may be because adoption is very costly behavior and because non-human primates form stable groups and have a good ability to recognise other group members.

"It's well known that groups of bonobos sometimes encounter and associate with each other, and that those belonging to different groups can interact tolerantly.

"However, I had never imagined that bonobos could adopt infants from outside of their groups, so these cases were quite surprising."

The researchers plan to continue their observations of the bonobo groups once Covid-19 restrictions allow.

INFORMATION:

The research, which also included the Research Center for Ecology and Forestry, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the European Research Council, the National Geographic Foundation for Science and Exploration, and The Leading Program in Primatology and Wildlife Science of Kyoto University.

ENDS

Researchers at Seattle's Institute for Systems Biology and their collaborators looked at the electronic health records of nearly 630,000 patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2, and found stark disparities in COVID-19 outcomes -- odds of infection, hospitalization, and in-hospital mortality -- between White and non-White minority racial and ethnic groups. The work was published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

The team looked at sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients who were part of the Providence healthcare system in Washington, Oregon and California. These ...

Metformin, a drug used to treat type-2 diabetes, could help reduce chronic inflammation in people living with HIV (PLWH) who are being treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART), according to researchers at the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM).

Although ART has helped improved the health of PLWH, they are nevertheless at greater risk of developing complications related to chronic inflammation, such as cardiovascular disease. These health problems are mainly due to the persistence of HIV reservoirs in the patients' long-lived memory T cells and to the constant activation of their immune system.

In a pilot study published recently in ...

MADISON, Wis. -- Scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have developed a way to use a cell's own recycling machinery to destroy disease-causing proteins, a technology that could produce entirely new kinds of drugs.

Some cancers, for instance, are associated with abnormal proteins or an excess of normally harmless proteins. By eliminating them, researchers believe they can treat the underlying cause of disease and restore a healthy balance in cells.

The new technique builds on an earlier strategy by researchers and pharmaceutical companies to remove proteins residing inside of a cell, and expands on this system to include proteins ...

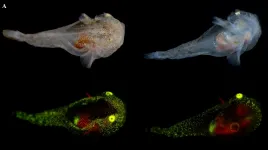

For the first time, scientists have documented biofluorescence in an Arctic fish species. The study, led by researchers at the American Museum of Natural History who spent hours in the icy waters off of Greenland where the red-and-green-glowing snailfish was found, is published today in the American Museum Novitates.

"Overall, we found marine fluorescence to be quite rare in the Arctic, in both invertebrate and vertebrate lineages," said John Sparks, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History's Department of Ichthyology and one of the authors of the ...

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic changed the higher education experience for students across the United States, with more than 90 percent of institutions reporting a shift in education delivery with the arrival of COVID-19.

The rapid transition to remote study came with its own learning curve for students and faculty alike. But for many students with disabilities, the shift offered new educational modalities as well as challenges - and the hope that some changes will continue after the threat of the virus subsides.

"This was a really unique, historical moment," says Nicholas Gelbar '06 (ED), '07 MEd, '13 Ph.D., an associate research professor with the Neag School of Education. "Remote learning, ...

Millions of children weighing less than 15kg are currently denied access to Ivermectin treatment due to insufficient safety data being available to support a change to the current label indication. The WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN)'s new meta-analysis published today provides evidence that supports removing this barrier and improving treatment equity. ...

DURHAM, N.H.-- Researchers at the University of New Hampshire have found that more than 50% of children in high-risk populations in the United States are not receiving behavioral health services that could improve their developmental outcomes when it comes to mental and physical health problems.

In their END ...

HOUSTON - (March 18, 2021) - If you're looking for one technique to maximize photon output from plasmons, stop. It takes two to wrangle.

Rice University physicists came across a phenomenon that boosts the light from a nanoscale device more than 1,000 times greater than they anticipated.

When looking at light coming from a plasmonic junction, a microscopic gap between two gold nanowires, there are conditions in which applying optical or electrical energy individually prompted only a modest amount of light emission. Applying both together, however, caused a burst of light that far exceeded ...

When it comes to recreational crabbing--one of the most iconic pastimes along Maryland's shores--the current estimate of 8% of "total male commercial harvest" runs just a little too low. Biologists, with local community support, found stronger evidence for the underestimate in the END ...

As one of the founding members of the International Rye Genome Sequencing Group (IRGSG), the University of Maryland (UMD) co-published the first full reference genome sequence for rye in Nature Genetics. UMD and international collaborators saw the need for a reference genome of this robust small grain to allow for the tracking of its useful genes and fulfill its potential for crop improvement across all major varieties of small grains, including wheat, barley, triticale (a cross between wheat and rye that is gaining popularity), and rye. Following the model of international collaboration used ...