(Press-News.org) At the heart of clouds are ice crystals. And at the heart of ice crystals, often, are aerosol particles - dust in the atmosphere onto which ice can form more easily than in the open air.

It's a bit mysterious how this happens, though, because ice crystals are orderly structures of molecules, while aerosols are often disorganized chunks. New research by Valeria Molinero, distinguished professor of chemistry, and Atanu K. Metya, now at the Indian Institute of Technology Patna, shows how crystals of organic molecules, a common component of aerosols, can get the job done.

The story is more than that, though - it's a throwback to Cold War-era cloud seeding research and an investigation into a peculiar memory effect that sees ice form more readily on these crystals the second time around.

The research, funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, is published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Throwback to cloud seeding

Molinero's research is focused on how ice forms, particularly the process of nucleation, which is the beginning of ice crystal formation. Under the right conditions, water molecules can nucleate ice on their own. But often some other material, called a nucleant, can help the process along.

After several studies on the ways that proteins can help form ice, Molinero and Metya turned their attention to organic ice nucleants (as used here, "organic" means organic compounds containing carbon) because they are similar to the ice-producing proteins and are found in airborne aerosols.

But a review of the scientific literature found that the papers discussing ice nucleation by organic compounds came from the 1950s and 1960s, with very little follow-up work after that until very recently.

"That made me really curious," Molinero says, "because there is a lot of interest now on organic aerosols and whether and how they promote the formation of ice in clouds, but all this new literature seemed dissociated from these early fundamental studies of organic ice nucleants."

Additional research revealed that the early work on organic ice nucleants was related to the study of cloud seeding, a post-war line of research into how particles (primarily silver iodide) could be introduced into the atmosphere to encourage cloud formation and precipitation. Scientists explored the properties of organic compounds as ice nucleants to see if they might be cost-effective alternatives to silver iodide.

But cloud seeding research collapsed in the 1970s after political pressures and fears of weather modification led to a ban on the practice in warfare. Funding and interest in organic ice nucleants dried up until recently, when climate research spurred a renewed interest in the chemistry of ice formation in the atmosphere.

"There has been a growing interest in ice nucleation by organic aerosols in the last few years, but no connection to these old studies on organic crystals," Molinero says. "So, I thought it was time to "rescue" them into the modern literature."

Going all classic

Phloroglucinol is one of the organic nucleants studied in the mid-20th century. It showed promise for controlling fog, but less for cloud seeding. Molinero and Metya revisited phloroglucinol as it proved potent at ice nucleation in the lab.

One question to answer is whether phloroglucinol nucleates ice through classical or non-classical processes. When ice nucleates on its own, without any surfaces or other molecules, the only hurdle to overcome is forming a stable crystallite of ice (only about 500 molecules in size under some conditions) that other molecules can build on to grow an ice crystal. That's classical nucleation.

Non-classical nucleation, involving a nucleant surface, occurs when a layer of water molecules assembles on the surface on which other water molecules can organize into a crystal lattice. The hurdle to overcome in non-classical nucleation is the formation of the monolayer.

Which applies to phloroglucinol? In the 1960s, researcher L.F. Evans concluded that it was non-classical. "I am still amazed he was able to deduce the existence of a monolayer and infer the mechanism was non-classical from experiments of freezing as a function of temperature alone!" Molinero says. But Molinero and Metya, using molecular simulations of how ice forms, found that it's more complicated.

"We find that the step that really decides whether water transforms to ice or not is not the formation of the monolayer but the growth of an ice crystallite on top," Molinero says. "That makes ice formation by organics classical although no less fascinating."

Holding on to memories of ice

The researchers also used their simulation methods to investigate an interesting memory effect previously observed with organic and other nucleants. When ice is formed, melted and formed again using these nucleants, the second round of crystallization is more effective than the first. It's assumed that the ice melts completely between crystallizations, and researchers have posed several potential explanations.

Molinero and Metya found that the memory effect isn't due to the ice changing the nucleant surface, nor to the monolayer of water persisting on the nucleant surface after melting. Instead, their simulations supported an explanation where crevices in the nucleant can hold on to small amounts of ice that melt at higher temperatures than the rest of the ice in the experiment. If these crevices are adjacent to one of the nucleant crystal surfaces that's good at forming ice, then it's off to the races when the second round of freezing begins.

Something in the air

Other mysteries still remain - the mid-century studies of organic crystals found that at high pressures, around 1500 times atmospheric pressure, that the crystals are as efficient at organizing water molecules into ice as an ice crystal itself. Why? That's the focus of Molinero's next experiments.

More immediately, though, phloroglucinol is a naturally-occurring compound in the atmosphere, so anything that researchers can learn about it and other organic nucleants can help explain the ability of aerosols to nucleate ice and regulate the formation of clouds and precipitation.

"It would be important to investigate whether small crystallites of these crystalline ice nucleants are responsible for the baffling ice nucleation ability of otherwise amorphous organic aerosols," Molinero says.

INFORMATION:

Find the full study here.

Observations of groups of wild bonobos, reported in Scientific Reports, suggest that two infants may have been adopted by adult females belonging to different social groups. The findings may represent the first report of cross-group adoption in wild bonobos, and potentially also the first cases of cross-group adoption in wild apes.

Bonobos form social groups of multiple males and females that sometimes temporarily associate with one another. Nahoko Tokuyama and colleagues observed four groups of wild bonobos between April 2019 and March 2020 in the Luo Scientific Reserve in Wamba, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The authors identified two infants whom ...

Newly excavated skeletal remains of an ankylosaurid -- a large armoured herbivore that lived during the Cretaceous Period -- may indicate that members of this family of dinosaurs were able to dig, according to a study published in Scientific Reports. The specimen, known as MPC-D 100/1359, may further our understanding of ankylosaurid behaviour during the Late Cretaceous (84-72 million years ago).

Yuong-Nam Lee and colleagues excavated the skeletal elements of MPC-D 100/1359 from a deposit of the Baruungoyot Formation in the southern Gobi Desert, Mongolia, ...

UC Santa Cruz researchers published a new study--in collaboration with UC Water and the Sierra Nevada Research Institute at UC Merced--that suggests covering California's 6,350 km network of public water delivery canals with solar panels could be an economically feasible means of advancing both renewable energy and water conservation.

The concept of "solar canals" has been gaining momentum around the world as climate change increases the risk of drought in many regions. Solar panels can shade canals to help prevent water loss through evaporation, and some types of solar panels also work better over canals, because the cooler environment keeps them from overheating. ...

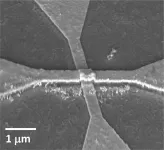

Training neural networks to perform tasks, such as recognizing images or navigating self-driving cars, could one day require less computing power and hardware thanks to a new artificial neuron device developed by researchers at the University of California San Diego. The device can run neural network computations using 100 to 1000 times less energy and area than existing CMOS-based hardware.

Researchers report their work in a paper published Mar. 18 in Nature Nanotechnology.

Neural networks are a series of connected layers of artificial neurons, where the output of one layer provides the ...

From swallowing pills to injecting insulin, patients frequently administer their own medication. But they don't always get it right. Improper adherence to doctors' orders is commonplace, accounting for thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in medical costs annually. MIT researchers have developed a system to reduce those numbers for some types of medications.

The new technology pairs wireless sensing with artificial intelligence to determine when a patient is using an insulin pen or inhaler, and flags potential errors in the patient's administration method. "Some past work reports that up to 70% of patients do not ...

A study by Monash University has uncovered that liver metabolism is disrupted in people with obesity-related type 2 diabetes, which contributes to high blood sugar and muscle loss - also known as skeletal muscle atrophy.

Using human trials as well as mouse models, collaborative research led by Dr Adam Rose at Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute has found the liver metabolism of the amino acid alanine is altered in people with obesity-related type 2 diabetes. By selectively silencing enzymes that break down alanine in liver cells, high blood sugar and muscle loss can be reversed by the restoration of skeletal muscle protein synthesis, a critical determinant of muscle size and strength.

The research, published today in Nature Metabolism, has shown the altered liver metabolism ...

Scientists have witnessed bonobo apes adopting infants who were born outside of their social group for the first time in the wild.

Researchers, including psychologists at Durham University, UK, twice saw the unusual occurrence among bonobos in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in central Africa.

They say their findings give us greater insight into the parental instincts of one of humans' closest relatives and could help to explain the emotional reason behind why people readily adopt children who they have had no previous connection with.

The research, led by Kyoto University, in Japan, is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Researchers observed a number of bonobo groups over several years in the Wamba area of ...

Researchers at Seattle's Institute for Systems Biology and their collaborators looked at the electronic health records of nearly 630,000 patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2, and found stark disparities in COVID-19 outcomes -- odds of infection, hospitalization, and in-hospital mortality -- between White and non-White minority racial and ethnic groups. The work was published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

The team looked at sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients who were part of the Providence healthcare system in Washington, Oregon and California. These ...

Metformin, a drug used to treat type-2 diabetes, could help reduce chronic inflammation in people living with HIV (PLWH) who are being treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART), according to researchers at the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM).

Although ART has helped improved the health of PLWH, they are nevertheless at greater risk of developing complications related to chronic inflammation, such as cardiovascular disease. These health problems are mainly due to the persistence of HIV reservoirs in the patients' long-lived memory T cells and to the constant activation of their immune system.

In a pilot study published recently in ...

MADISON, Wis. -- Scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have developed a way to use a cell's own recycling machinery to destroy disease-causing proteins, a technology that could produce entirely new kinds of drugs.

Some cancers, for instance, are associated with abnormal proteins or an excess of normally harmless proteins. By eliminating them, researchers believe they can treat the underlying cause of disease and restore a healthy balance in cells.

The new technique builds on an earlier strategy by researchers and pharmaceutical companies to remove proteins residing inside of a cell, and expands on this system to include proteins ...