(Press-News.org) Anyone who has watched an infant's eyes follow a dangling trinket dancing in front of them knows that babies are capable of paying attention with laser focus.

But with large areas of their young brains still underdeveloped, how do they manage to do so?

Using an approach pioneered at Yale that uses fMRI (or functional magnetic resonance imaging) to scan the brains of awake babies, a team of university psychologists show that when focusing their attention infants under a year of age recruit areas of their frontal cortex, a section of the brain involved in more advanced functions that was previously thought to be immature in babies. The findings were published March 16 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Attention is the gateway to what infants perceive and learn," said Nick Turk-Browne, professor of psychology at Yale and senior author of the paper. "Attention is the bouncer at the door, determining what information gets into the brain, which eventually creates memories, language, and thought."

Most previous research related to attention in babies has depended upon tracking their gaze while they are presented with visual stimuli, a process that theoretically offers insights into what is going on in their minds. Left unanswered are questions about which sections of the brain are involved in these responses, and how and why they allocate attention in these ways.

Attention in babies could depend upon on sensory areas of the brain, which process stimuli such as touch and visual stimuli and helps them react to the external world. These brain regions develop earlier in infancy than regions of the frontal cortex, which are usually associated with internal functions such as control, planning, and reasoning.

The ability to use brain imaging with infants allowed "us to look behind the mirror," for the neural origins of attention, Turk-Browne said.

For the study, they used the new fMRI technology to track the neural activity of 20 babies aged from 3 to 12 months, tracking which regions of their brains were activated as they focused their attention in response to a series of images.

In a series of tests, the babies were shown a screen on which a target would appear on either the left or right side. In each case, these appearances were preceded by one of three visual cues signaling where the target would appear: on the same side that the target would appear, on both sides of the screen (thus uninformative), or on the opposite side. Researchers monitored the babies' eye movements as they completed these tasks.

See a video of the experiment.

As expected, the babies were much quicker to move their eyes to the target when first presented the correct cue, confirming that the cues had focused their attention. Simultaneously, the researchers used brain imaging technology to see which areas of the brain were recruited during these tasks. In addition to sensory areas of the brain, they found that activity also increased in two areas of the frontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the middle frontal gyrus, areas of the brain that when fully developed are involved in controlling adult attention.

"This doesn't mean these regions play the same role in babies as in adults, but it does show that infants use them to explore their visual world," said Cameron Ellis, a Ph.D. candidate in psychology at Yale and first author of the paper.

Studying how the brain is enlisted during development "will help researchers uncover the foundations of human learning, which could one day help improve early-childhood education and reveal the roots of neurodevelopmental disorders," Ellis said.

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the study are Yale graduate students Lena Skalaban and Tristan Yates.

At the heart of clouds are ice crystals. And at the heart of ice crystals, often, are aerosol particles - dust in the atmosphere onto which ice can form more easily than in the open air.

It's a bit mysterious how this happens, though, because ice crystals are orderly structures of molecules, while aerosols are often disorganized chunks. New research by Valeria Molinero, distinguished professor of chemistry, and Atanu K. Metya, now at the Indian Institute of Technology Patna, shows how crystals of organic molecules, a common component of aerosols, can get the ...

Observations of groups of wild bonobos, reported in Scientific Reports, suggest that two infants may have been adopted by adult females belonging to different social groups. The findings may represent the first report of cross-group adoption in wild bonobos, and potentially also the first cases of cross-group adoption in wild apes.

Bonobos form social groups of multiple males and females that sometimes temporarily associate with one another. Nahoko Tokuyama and colleagues observed four groups of wild bonobos between April 2019 and March 2020 in the Luo Scientific Reserve in Wamba, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The authors identified two infants whom ...

Newly excavated skeletal remains of an ankylosaurid -- a large armoured herbivore that lived during the Cretaceous Period -- may indicate that members of this family of dinosaurs were able to dig, according to a study published in Scientific Reports. The specimen, known as MPC-D 100/1359, may further our understanding of ankylosaurid behaviour during the Late Cretaceous (84-72 million years ago).

Yuong-Nam Lee and colleagues excavated the skeletal elements of MPC-D 100/1359 from a deposit of the Baruungoyot Formation in the southern Gobi Desert, Mongolia, ...

UC Santa Cruz researchers published a new study--in collaboration with UC Water and the Sierra Nevada Research Institute at UC Merced--that suggests covering California's 6,350 km network of public water delivery canals with solar panels could be an economically feasible means of advancing both renewable energy and water conservation.

The concept of "solar canals" has been gaining momentum around the world as climate change increases the risk of drought in many regions. Solar panels can shade canals to help prevent water loss through evaporation, and some types of solar panels also work better over canals, because the cooler environment keeps them from overheating. ...

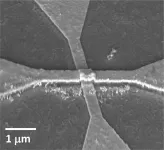

Training neural networks to perform tasks, such as recognizing images or navigating self-driving cars, could one day require less computing power and hardware thanks to a new artificial neuron device developed by researchers at the University of California San Diego. The device can run neural network computations using 100 to 1000 times less energy and area than existing CMOS-based hardware.

Researchers report their work in a paper published Mar. 18 in Nature Nanotechnology.

Neural networks are a series of connected layers of artificial neurons, where the output of one layer provides the ...

From swallowing pills to injecting insulin, patients frequently administer their own medication. But they don't always get it right. Improper adherence to doctors' orders is commonplace, accounting for thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in medical costs annually. MIT researchers have developed a system to reduce those numbers for some types of medications.

The new technology pairs wireless sensing with artificial intelligence to determine when a patient is using an insulin pen or inhaler, and flags potential errors in the patient's administration method. "Some past work reports that up to 70% of patients do not ...

A study by Monash University has uncovered that liver metabolism is disrupted in people with obesity-related type 2 diabetes, which contributes to high blood sugar and muscle loss - also known as skeletal muscle atrophy.

Using human trials as well as mouse models, collaborative research led by Dr Adam Rose at Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute has found the liver metabolism of the amino acid alanine is altered in people with obesity-related type 2 diabetes. By selectively silencing enzymes that break down alanine in liver cells, high blood sugar and muscle loss can be reversed by the restoration of skeletal muscle protein synthesis, a critical determinant of muscle size and strength.

The research, published today in Nature Metabolism, has shown the altered liver metabolism ...

Scientists have witnessed bonobo apes adopting infants who were born outside of their social group for the first time in the wild.

Researchers, including psychologists at Durham University, UK, twice saw the unusual occurrence among bonobos in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in central Africa.

They say their findings give us greater insight into the parental instincts of one of humans' closest relatives and could help to explain the emotional reason behind why people readily adopt children who they have had no previous connection with.

The research, led by Kyoto University, in Japan, is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Researchers observed a number of bonobo groups over several years in the Wamba area of ...

Researchers at Seattle's Institute for Systems Biology and their collaborators looked at the electronic health records of nearly 630,000 patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2, and found stark disparities in COVID-19 outcomes -- odds of infection, hospitalization, and in-hospital mortality -- between White and non-White minority racial and ethnic groups. The work was published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

The team looked at sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients who were part of the Providence healthcare system in Washington, Oregon and California. These ...

Metformin, a drug used to treat type-2 diabetes, could help reduce chronic inflammation in people living with HIV (PLWH) who are being treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART), according to researchers at the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM).

Although ART has helped improved the health of PLWH, they are nevertheless at greater risk of developing complications related to chronic inflammation, such as cardiovascular disease. These health problems are mainly due to the persistence of HIV reservoirs in the patients' long-lived memory T cells and to the constant activation of their immune system.

In a pilot study published recently in ...