(Press-News.org) In new findings published online March 18, 2021 in the journal Cancer Cell, an international team of researchers, led by scientists at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center, describe how pancreatic cancer cells use an alternative method to find necessary nutrients, defying current therapies, to help them grow and spread.

Pancreatic cancer accounts for roughly 3 percent of all cancers in the United States, but it is among the most aggressive and deadly, resulting in 7 percent of all cancer deaths annually. Pancreatic cancer is especially deadly once it metastasizes, with the number of people who are alive five years later declining from 37 percent to just 3 percent.

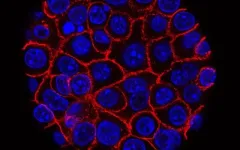

All cancer cells require a constant supply of nutrients. Some types of cancer achieve this by creating their own vascular networks to pull in nutrients from the host's blood supply. But other cancers, notably pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, are surrounded by a thick layer of connective tissue and extracellular molecules (the so-called tumor stroma) that act not just as a sort of a dividing line between malignant cells and normal host tissues, but also as a hindrance to cancer cells obtaining sufficient resources, including blood supply.

As a result, pancreatic and other nutritionally stressed cancers employ a number of adaptive mechanisms to avoid death by starvation, a risk particularly high in rapidly growing tumors. One such mechanism is autophagy or self-eating. Autophagy allows nutritionally stressed cancers to digest intracellular proteins, especially denatured or damaged proteins, and use the liberated amino acid building blocks as an energy source to fuel their metabolism.

Past research indicating autophagy is elevated in pancreatic cancer gave rise to the idea that inhibiting self-eating might be used to starve tumors. Yet, multiple clinical trials using compounds that inhibit autophagic protein degradation combined with traditional chemotherapy, did not produce any added therapeutic benefit compared to chemotherapy alone, said Michael Karin, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Pharmacology and Pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

In the new study, Hua Su, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Karin's lab and first author of the study, and collaborators investigated why pancreatic cancers survive autophagy and, in fact, appear to thrive. They found that inhibition of autophagy resulted in rapid upregulation or increased activity of a different nutrient procurement pathway called macropinocytosis, derived from the Greek for "large drinking or gulping."

Macropinocytosis enables autophagy-compromised and nutritionally stressed cancer cells to take up exogenous proteins (found outside the cell), digest them and use their amino acids for energy generation. "This explains why autophagy inhibitors fail to starve pancreatic cancer and cannot induce its regression," said Su. "Once autophagy is inhibited, cancer cells simply resort to a different mechanism to feed themselves."

In experiments using mouse cancer models and human pancreatic cancers grown in mice, Su and colleagues found that a combination of autophagy and macropinocytosis inhibitors resulted in rapid and nearly complete tumor regression.

"These results provide another example of the plastic nature of pancreatic cancer metabolism," said senior author Karin. "It also shows that combined inhibition of the two major nutrient procurement pathways can result in a successful blockade of energy supply resulting in tumor starvation and consequent shrinkage."

Study co-author Andrew Lowy, MD, chief of the Division of Surgical Oncology at Moores Cancer Center at UC San Diego Health and a professor of surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine, said the new data demonstrate the promise of targeting tumor metabolism as a treatment strategy and that success will likely require combining multiple agents for multiple targets.

"I believe that these findings are exciting and support the idea that we will make significant impact against this very difficult disease in the near-future," Lowy said.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors include: Fei Yang, Rao Fu, Xiaohong Pu and Beicheng Sun, Nanjing University Medical School; Xin Li and Yinling Hu, National Cancer Institute; Randall French, Evangeline Mose, Brittney Trinh, Junlai Liu, Laura Antonucci, Yuan Liu, Avi Kumar and Christian M. Metallo, UC San Diego; Jelena Todoric, UC San Diego and Medical University of Vienna; Maria Diaz-Meco and Jorge Moscat, Weill Cornell Medicine.

Smart glass can change its color quickly through electricity. A new material developed by chemists of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) in Munich has now set a speed record for such a change.

On the highway at night. It rains, the bright headlights of the car behind you are blinding. How convenient to have an automatically dimming rearview mirror in such a case. Technically, this helpful extra is based on electrochromic materials. When a voltage is applied, their light absorption and color change. Controlled by a light sensor, the rearview mirror can thus filter out strongly dazzling light.

Recently, experts discovered that, in addition to established inorganic electrochromic materials, a new generation of highly ordered lattice structures can also be equipped ...

KINSHASA, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (March 18, 2021) - A new study in the journal Conservation Science and Practice finds that restaurants in urban areas in Central Africa play a key role in whether protected wildlife winds up on the menu.

The study, by a team of scientists from Michigan State University, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), and University of Maryland, used a crime science "hot product" approach, which looks at frequently stolen items coveted by thieves. The approach offered new insights into wildlife targeted by the urban wild meat trade and can inform urban wildlife policies.

The study engaged lower, middle, and upper-level tiered restaurants to understand which species were traded. ...

Detailed, new analysis published this week in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) Open highlights significant concerns about a growing issue of sex selective abortion of girls in Nepal.

Drawing on census data from 2011 and follow-on survey data from 2016, the social scientists estimate that roughly one in 50 girl births were 'missing' from records (i.e. had been aborted) between 2006-11 (22,540 girl births in total). In the year before the census (June 2010 - June 2011) this had risen to one in 38.

For certain areas of the country, the practice was more widespread. In Arghakhanchi, the most affected district, one in every six girl births were 'missing' in census data. In the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal's main urban centre, around 115 boys are born for ...

Anyone who has watched an infant's eyes follow a dangling trinket dancing in front of them knows that babies are capable of paying attention with laser focus.

But with large areas of their young brains still underdeveloped, how do they manage to do so?

Using an approach pioneered at Yale that uses fMRI (or functional magnetic resonance imaging) to scan the brains of awake babies, a team of university psychologists show that when focusing their attention infants under a year of age recruit areas of their frontal cortex, a section of the brain involved in more advanced functions that was previously thought to be immature in babies. The findings were ...

At the heart of clouds are ice crystals. And at the heart of ice crystals, often, are aerosol particles - dust in the atmosphere onto which ice can form more easily than in the open air.

It's a bit mysterious how this happens, though, because ice crystals are orderly structures of molecules, while aerosols are often disorganized chunks. New research by Valeria Molinero, distinguished professor of chemistry, and Atanu K. Metya, now at the Indian Institute of Technology Patna, shows how crystals of organic molecules, a common component of aerosols, can get the ...

Observations of groups of wild bonobos, reported in Scientific Reports, suggest that two infants may have been adopted by adult females belonging to different social groups. The findings may represent the first report of cross-group adoption in wild bonobos, and potentially also the first cases of cross-group adoption in wild apes.

Bonobos form social groups of multiple males and females that sometimes temporarily associate with one another. Nahoko Tokuyama and colleagues observed four groups of wild bonobos between April 2019 and March 2020 in the Luo Scientific Reserve in Wamba, Democratic Republic of the Congo. The authors identified two infants whom ...

Newly excavated skeletal remains of an ankylosaurid -- a large armoured herbivore that lived during the Cretaceous Period -- may indicate that members of this family of dinosaurs were able to dig, according to a study published in Scientific Reports. The specimen, known as MPC-D 100/1359, may further our understanding of ankylosaurid behaviour during the Late Cretaceous (84-72 million years ago).

Yuong-Nam Lee and colleagues excavated the skeletal elements of MPC-D 100/1359 from a deposit of the Baruungoyot Formation in the southern Gobi Desert, Mongolia, ...

UC Santa Cruz researchers published a new study--in collaboration with UC Water and the Sierra Nevada Research Institute at UC Merced--that suggests covering California's 6,350 km network of public water delivery canals with solar panels could be an economically feasible means of advancing both renewable energy and water conservation.

The concept of "solar canals" has been gaining momentum around the world as climate change increases the risk of drought in many regions. Solar panels can shade canals to help prevent water loss through evaporation, and some types of solar panels also work better over canals, because the cooler environment keeps them from overheating. ...

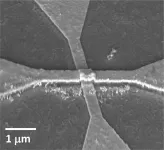

Training neural networks to perform tasks, such as recognizing images or navigating self-driving cars, could one day require less computing power and hardware thanks to a new artificial neuron device developed by researchers at the University of California San Diego. The device can run neural network computations using 100 to 1000 times less energy and area than existing CMOS-based hardware.

Researchers report their work in a paper published Mar. 18 in Nature Nanotechnology.

Neural networks are a series of connected layers of artificial neurons, where the output of one layer provides the ...

From swallowing pills to injecting insulin, patients frequently administer their own medication. But they don't always get it right. Improper adherence to doctors' orders is commonplace, accounting for thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in medical costs annually. MIT researchers have developed a system to reduce those numbers for some types of medications.

The new technology pairs wireless sensing with artificial intelligence to determine when a patient is using an insulin pen or inhaler, and flags potential errors in the patient's administration method. "Some past work reports that up to 70% of patients do not ...