(Press-News.org) A UCLA-led research team has identified a chemical cocktail that enables the production of large numbers of muscle stem cells, which can self-renew and give rise to all types of skeletal muscle cells.

The advance could lead to the development of stem cell-based therapies for muscle loss or damage due to injury, age or disease. The research was published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Muscle stem cells are responsible for muscle growth, repair and regeneration following injury throughout a person's life. In fully grown adults, muscle stem cells are quiescent -- they remain inactive until they are called to respond to injury by self-replicating and creating all of the cell types necessary to repair damaged tissue.

But that regenerative capacity decreases as people age; it also can be compromised by traumatic injuries and by genetic diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

"Muscle stem cell-based therapies show a lot of promise for improving muscle regeneration, but current methods for generating patient-specific muscle stem cells can take months," said Song Li, the study's senior author and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA.

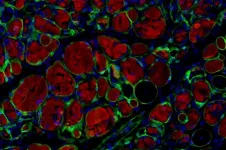

Li and his colleagues identified a chemical cocktail -- a combination of the root extract forskolin and the small molecule RepSox -- that can efficiently create large numbers of muscle stem cells within 10 days. In mouse studies, the researchers demonstrated two potential avenues by which the cocktail could be used as a therapy.

The first method uses cells found in the skin called dermal myogenic cells, which have the capacity to become muscle cells. The team discovered that treating dermal myogenic cells with the chemical cocktail drove them to produce large numbers of muscle stem cells, which could then be transplanted into injured tissue.

Li's team tested that approach in three groups of mice with muscle injuries: adult (8-week-old) mice, elderly (18-month-old) mice and adult mice with a genetic mutation similar to the one that causes Duchenne in humans.

Four weeks after the cells were transplanted, the muscle stem cells had integrated into the damaged muscle and significantly improved muscle function in all three groups of mice.

For the second method, Li's team used nanoparticles to deliver the chemical cocktail into damaged muscle tissue. The nanoparticles, which are about one one-hundredth the size of a grain of sand, are made of the same material as dissolvable surgical stitches, and they are designed to release the chemicals slowly as they break down.

The second approach also produced a robust repair response in all three types of mice. When injected into injured muscle, the nanoparticles migrated throughout the injured area and released the chemicals, which activated the quiescent muscle stem cells to begin dividing.

While both techniques were successful, the key benefit of the second one is that it eliminated the need for growing cells in the lab -- all of the muscle stem cell activation and regeneration takes place inside the body.

The team was particularly surprised to find that the second method was effective even in elderly mice, in spite of the fact that as animals age, the environment that surrounds and supports muscle stem cells becomes less effective.

"Our chemical cocktail enabled muscle stem cells in elderly mice to overcome their adverse environment and launch a robust repair response," said Li, who is also chair of bioengineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering and professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

In future studies, the research team will attempt to replicate the results in human cells and monitor the effects of the therapy in animals for a longer period. The experiments should help determine if either approach could be used as a one-time treatment for patients with serious injuries.

Li noted that neither approach would fix the genetic defect that causes Duchenne or other genetic muscular dystrophies. However, the team envisions that muscle stem cells generated from a healthy donor's skin cells could be transplanted into a muscular dystrophy patient's muscle -- such as in the lungs -- which could extend their lifespan and improve their quality of life.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Li, other UCLA contributors include assistant project scientist Jun Fang, professors James Tidball and Kym Faull, and research scientist Jennifer Soto. Scientists from UC Berkeley, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan also contributed to the study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the NIH under the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award, the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center Research Award Program and the UCLA Medical Scientist Training Program.

Researchers from Skoltech were part of a research consortium studying a case of vertical COVID-19 transmission from mother to her unborn child that resulted in major complications in the pregnancy, premature birth and death of the child. The consortium used a Skoltech-developed proteomics method to verify the diagnosis. The paper was published in the journal Viruses.

The effects of SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus, on maternal and perinatal outcomes are poorly understood due to limited data and research in pregnant women with COVID-19. There is some evidence suggesting vertical transmission from mother to fetus during pregnancy is possible, as, for instance, in China, immunoglobulin ...

Dogs infected with the Leishmania parasite smell more attractive to female sand flies than males, say researchers.

The study published in PLOS Pathogens is led by Professor Gordon Hamilton of Lancaster University.

In Brazil, the parasite Leishmania infantum is transmitted by the bite of infected female Lutzomyia longipalpis sand flies.

Globally over 350 million people are at risk of leishmaniasis, with up to 300,000 new cases annually. In Brazil alone there are approximately 4,500 deaths each year from the visceral form of the disease and children under 15 years old are more likely to be affected.

Leishmania parasites ...

WASHINGTON -- Even as vaccines are becoming more readily available in the U.S., protecting against the asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic spread of the virus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19 is key to ending the pandemic, say two Georgetown infectious disease experts.

In their Perspective, " END ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Much of the carbon in space is believed to exist in the form of large molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Since the 1980s, circumstantial evidence has indicated that these molecules are abundant in space, but they have not been directly observed.

Now, a team of researchers led by MIT Assistant Professor Brett McGuire has identified two distinctive PAHs in a patch of space called the Taurus Molecular Cloud (TMC-1). PAHs were believed to form efficiently only at high temperatures -- on Earth, they occur as byproducts of burning fossil fuels, and they're also found in char marks on grilled ...

One of great mysteries of human biology is how a single cell can give rise to the 37 trillion cells contained in the average body, each with its own specialized role. Researchers at Yale University and the Mayo Clinic have devised a way to recreate the earliest stages of cellular development that gives rise to such an amazing diversity of cell types.

Using skin cells harvested from two living humans, researchers in the lab of Yale's Flora Vaccarino were able to track their cellular lineage by identifying tiny variations or mutations contained within the genomes of those cells.

These "somatic" or non-inherited mutations are generated at each cell division during a human's development. The percentage of cells bearing the traces of any ...

The small intestine is ground zero for survival of animals. It is responsible for absorbing the nutrients crucial to life and it wards off toxic chemicals and life-threatening bacteria.

In a new study published March 18 in the journal Science, Yale researchers report the critical role played by the gut's immune system in these key processes. The immune system, they found, not only defends against pathogens but regulates which nutrients are taken in.

The findings may provide insights into origins of metabolic disease and malnutrition that is common in ...

93 million years ago, bizarre, winged sharks swam in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. This newly described fossil species, called Aquilolamna milarcae, has allowed its discoverers to erect a new family. Like manta rays, these 'eagle sharks' are characterised by extremely long and thin pectoral fins reminiscent of wings. The specimen studied was 1.65 metres long and had a span of 1.90 metres.

Aquilolamna milarcae had a caudal fin with a well-developed superior lobe, typical of most pelagic sharks, such as whale sharks and tiger sharks. Thus, its anatomical features thus ...

It's not just how hot the fires burn - it's also where they burn that matters. During the recent extreme fire season in Australia, which began in 2019 and burned into 2020, millions of tons of smoke particles were released into the atmosphere. Most of those particles followed a typical pattern, settling to the ground after a day or week; yet the ones created in fires burning in one corner of the country managed to blanket the entire Southern hemisphere for months. A pair of Israeli scientists managed to track puzzling January and February 2020 spikes in a measure of particle-laden haze to those fires, and then, in a paper recently published in Science, they ...

INDIANAPOLIS -- The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is keeping millions of Americans from their usual offices, as they find themselves still working at home. Even with the vaccine now being distributed, working from home may still be the future for some, and new research suggests the resulting work loneliness negatively impacts employee well-being. ...

Researchers who simulated early stages of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Wuhan, China, conclude that the virus was likely circulating earlier than has been described, possibly even in mid-October 2019. The findings do not reveal whether the virus that first emerged was less "fit" than the virus that spread throughout China, say the authors, but the estimates do further distance the first ("index") case from the outbreak at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which has received much attention. A concerted effort has been made to determine when the SARS-CoV-2 virus ...