(Press-News.org) Due to their tissue-like mechanical properties, hydrogels are being increasingly used for biomedical applications; a well-known example are soft contact lenses. These gel-like polymers consist of 90 percent water, are elastic and particularly biocompatible. Hydrogels that are also electrically conductive allow additional fields of application, for example in the transmission of electrical signals in the body or as sensors. An interdisciplinary research team of the Research Training Group (RTG) 2154 "Materials for Brain" at Kiel University (CAU) has now developed a method to produce hydrogels with an excellent level of electrical conductivity. What makes this method special is that the mechanical properties of the hydrogels are largely retained. This way they could be particularly well suited, for example, as a material for medical functional implants, which are used to treat certain brain diseases. The group's findings were now published in the journal Nano Letters.

"The elasticity of hydrogels can be adapted to various types of tissue in the body and even to the consistency of brain tissue. This is why we are particularly interested in these hydrogels as implant materials," explains materials scientist Margarethe Hauck, a doctoral researcher in RTG 2154 and one of the study's lead authors. As such, the interdisciplinary collaboration of materials and medical scientists focuses on the development of new materials for implants, for example for the release of active substances to treat brain diseases such as epilepsy, tumors or aneurysms. Conductive hydrogels could be used to control the release of active substances in order to treat certain diseases locally in a more targeted manner.

In order to produce electrically conductive hydrogels, conventional hydrogels are usually mixed with current-conducting nanomaterials that are made of metals or carbon, such as gold nanowires, graphene or carbon nanotubes. To achieve a good level of conductivity, a high concentration of nanomaterials is often required. However, this alters the original mechanical properties of the hydrogels, such as their elasticity, and thus impacts their interaction with the surrounding cells. "Cells are particularly sensitive to the nature of their environment. They feel most comfortable with materials around them whose properties correspond as closely as possible to their natural surroundings in the body," explains Christine Arndt, a doctoral researcher at the Institute for Materials Science at Kiel University and also lead author of the study.

Production method requires less graphene than previous approaches

In close collaboration with various working groups, the research team was now able to develop a hydrogel that boasts an ideal combination: it is not only electrically conductive but also retains its original level of elasticity. For conductivity, the scientists used graphene, a material that has already been used in other production approaches. "Graphene has outstanding electrical and mechanical properties and is also very light," says Dr Fabian Schütt, junior group leader in the Research Training Group, thus emphasising the advantages of the ultra-thin material, which consists of only one layer of carbon atoms. What makes this new method different is the amount of graphene used. "We are using significantly less graphene than previous studies, and as a result, the key properties of the hydrogel are retained," says Schütt about the current study, which he initiated.

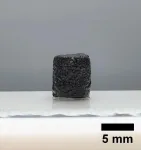

In order to achieve this objective, the scientists thinly coated a fine framework structure of ceramic microparticles with graphene flakes. Then they added the hydrogel polyacrylamide, which enclosed the framework structure, which was finally etched away. The thin graphene coating in the hydrogel remains unaffected by this process. The entire hydrogel is now streaked with graphene-coated microchannels, similar to an artificial nervous system.

Special 3D images by the Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht (HZG) demonstrate the highly electronic conductivity of the channel system: "Due to a multitude of connections between the individual graphene tubes, electrical signals always find their way through the material and make it extremely reliable", says Dr Berit Zeller-Plumhoff, Head of Department for Imaging and Data Science at HZG and an associate member in the RTG. With the help of high-intensity X-rays the mathematician took the images in a short time frame at the imaging beamline operated by the HZG at the storage ring PETRA III at the Deutsche Elektronensynchrotron DESY. And the three-dimensional network has yet another advantage: its stretchability enables it to adapt relatively flexibly to its environment.

Further fields of application in biomedicine and soft robotics conceivable

"With the collaborations between different working groups, the RTG offers ideal conditions for biomedical research questions that require an interdisciplinary approach," says Christine Selhuber-Unkel, first spokesperson of the RTG and now Professor of Molecular Systems Engineering at Heidelberg University. "This is a complex field of research as it combines both materials science and medicine and is likely to further develop enormously over the coming years, while the national and international demand for qualified specialists will increase - and this is what we want to prepare our doctoral researchers for in the best possible way," adds her successor Rainer Adelung, Professor of Functional Nanomaterials at Kiel University and spokesperson of the RTG since 2020.

In the future, various additional applications of the new conductive hydrogel are possible: Margarethe Hauck plans to develop a hydrogel that reacts to small changes in temperature and could release active substances in the brain in a controlled manner. Christine Arndt is working on how electrically conductive hydrogels can be used as biohybrid robots. The force that cells exert on their environment could be used here to drive miniaturised robotic systems.

INFORMATION:

Google Trends reveal how searches related to family and relationship behaviors, such as weddings, contraception, and abortions, changed during lockdowns in the US and Europe.

INFORMATION:

Link to publicly available article: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0248072

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0248072

...

How did life begin on Earth and could it exist elsewhere? Researchers at Simon Fraser University have isolated a genetic clue--an enzyme known as an RNA polymerase--that provides new insights about the origins of life. The research is published today in the journal Science.

Researchers in SFU molecular biology and biochemistry professor Peter Unrau's laboratory are working to advance the RNA World Hypothesis in answer to fundamental questions on life's beginnings.

The hypothesis suggests that life on our planet began with self-replicating ribonucleic acid (RNA) molecules, capable of not only carrying genetic information but also driving chemical reactions essential for life, prior to the evolution ...

In the future, droughts could be even more severe than those that struck parts of Germany in 2018. An analysis of climate data from the last millennium shows that several factors have to coincide to produce a megadrought: not only rising temperatures, but also the amount of solar radiation, as well as certain meteorological and ocean-circulation conditions in the North Atlantic, like those expected to arise in the future. A group of researchers led by the Alfred Wegener Institute have just released their findings in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Despite the precipitation this winter, which in ...

Large areas of forests regrowing in the Amazon to help reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, are being limited by climate and human activity.

The forests, which naturally regrow on land previously deforested for agriculture and now abandoned, are developing at different speeds. Researchers at the University of Bristol have found a link between slower tree-growth and land previously scorched by fire.

The findings were published today [date] in Nature Communications, and suggest a need for a better protection of these forests if they are to help mitigate the effects of climate change.

Global forests are expected to contribute a quarter of pledged mitigation under the ...

OSAKA, Japan. If you were given the option to eat a delicious meal by yourself, or share that meal with your loved ones, you would need as very good excuse ready if you chose the former. Turns out, fish share a similar inclination to look after each other.

For the first time ever, a research group led by researcher Shun Satoh and Masanori Kohda, professor of the Graduate School of Science, Osaka City University, have shown these altruistic tendencies in fish through a series of prosocial choice tasks (PCT) where they gave male convict cichlid fish two choices: the antisocial option of receiving food for themselves alone and the prosocial option of receiving food for themselves and their partner.

"As a result, it can be said that the convict cichlid ...

In a recent study led by the University of Bristol, scientists have shown how to simultaneously harness multiple forms of regulation in living cells to strictly control gene expression and open new avenues for improved biotechnologies.

Engineered microbes are increasingly being used to enable the sustainable and clean production of chemicals, medicines and much more. To make this possible, bioengineers must control when specific sets of genes are turned on and off to allow for careful regulation of the biochemical processes involved.

Their findings are reported today in the journal Nature Communications.

Veronica Greco, lead author ...

Scientists have discovered in more detail than ever before how the human body's immune system reacts to malaria and sickle cell disease.

The researchers from the universities of Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Exeter and Imperial College, London have published their findings in Nature Communications.

Every year there are ~200 million cases of malaria, which causes ~400,000 deaths.

As it causes resistance against malaria, the sickle cell disease mutation has spread widely, especially in people from Africa.

But if a child inherits a double dose of the gene - from both mother and father - they will develop ...

Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have for the first time observed photochemical processes inside the smallest particles in the air. In doing so, they discovered that additional oxygen radicals that can be harmful to human health are formed in these aerosols under everyday conditions. They report on their results today in the journal Nature Communications.

It is well known that airborne particulate matter can pose a danger to human health. The particles, with a maximum diameter of ten micrometres, can penetrate deep into lung tissue and settle ...

Sabrina L. Spencer, PhD, is a CU Boulder researcher and a CU Cancer Center member. Spencer recently won two awards: the Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovation Award (from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation) and the Emerging Leader Award (from The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research). The preliminary research she used to apply for the grants, "Melanoma subpopulations that rapidly escape MAPK pathway inhibition incur DNA damage and rely on stress signalling," was published in Nature Communications on March 19, 2021. We spoke to Spencer about the awards and how she plans to use them to ...

Researchers looking at miniscule levels of plutonium pollution in our soils have made a breakthrough which could help inform future 'clean up' operations on land around nuclear power plants, saving time and money.

Publishing in the journal Nature Communications, researchers show how they have measured the previously 'unmeasurable' and taken a step forward in differentiating between local and global sources of plutonium pollution in the soil.

By identifying the isotopic 'fingerprint' of trace-level quantities of plutonium in the soil which matched the ...