(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — University of Illinois researchers have found a key to keeping stem cells in their neutral state: It takes a soft touch.

In a paper published in the journal PLoS One, the researchers demonstrated that culturing mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) on a soft gel rather than on a hard plate or dish keeps them in their pluripotent state, a ground state with the ability to become any type of tissue. The soft substrate maintains homogeneous pluripotent colonies over long periods of time – without the need for expensive growth chemicals.

"This has huge applications in the future of regenerative medicine," said mechanical science and engineering professor Ning Wang, who co-led the group with animal sciences professor Tetsuya Tanaka. "It's an exciting area. There's still a lot of work to do, but our work is a step toward understanding the basic biology of stem cells."

The difficulty of maintaining mESC colonies that are homogeneously pluripotent has been one of the main obstacles in stem cell research. Pluripotent stem cells spontaneously differentiate, beginning to turn into specialized tissue types such as skin or muscle. Scientists use chemicals called growth factors to keep mESCs in their unchanged state, but even then it's not long before the culture is a mixture of cells in various stages of differentiation, with diverse gene expression and morphologies.

Such diversity in a sample makes it very difficult for researchers to induce a culture of stem cells to become a particular type of tissue – the ultimate goal of stem cell research.

"If we start from a homogenous population of undifferentiated cells, differentiation toward the tissue of our interest might become much more homogenous than we've been able to achieve," said Tanaka, who also is affiliated with the U. of I. Institute for Genomic Biology. "So then, in generating a specific cell type – the main application of pluripotent stem cells – I think that there is an advantage to having a homogeneous culture to start with."

After noticing that pluripotent mESCs tend to stick together in round colonies while cells on the colony edges in contact with the rigid growth plate tend to differentiate more quickly, the team decided to focus on mESC mechanics rather than chemistry. Since stem cells are 10 times softer than mature cells, the researchers wondered if the mechanical forces between the plate and the cells were spurring differentiation. Wang and Tanaka's earlier research found that even small mechanical forces could be used to direct cell differentiation; could mechanics also hamper differentiation?

The team did side-by-side comparisons of mESCs grown on a traditional medium with growth factor and mESCs grown on a soft gel with the same stiffness as the cells, both with and without growth factor. They found that cells grown on the soft gel had greater homogeneity and pluripotency, even without growth factor, and even more than three months and 20 passages later.

"It's two sides of the coin: Mechanical force can induce differentiation, and here we said if you can lower the forces between the substrate and the cells, they stay pluripotent. They are complementary processes," Wang said. "Our paper shows that mechanical environment plays at least as important a role as chemical growth factors, if not greater. In vivo, cells produce growth factors for a short time and then they stop. On the other hand, mechanical forces bear on every cell all the time."

Next, the researchers want to try their soft-substrate method with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), mature cells that have been genetically reprogrammed to a pluripotent state. These cells hold a lot of promise for medical applications, but are notoriously hard to culture and not as well understood as embryonic cells.

"We can try culturing mouse iPSCs on the same soft substrate and see if the same benefit applies to achieve homogenous stem cell cultures," Tanaka said. "If that's the case, the impact would be significant."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the University of Illinois. Co-authors were graduate students Farhan Chowdhury, Yanzhen Li and Yeh-Chuin Poh, and visiting scholar Tamaki Yokohama-Tamaki.

Editor's note: To contact Tetsuya Tanaka, call 217-244-2522; e-mail ttanaka@illinois.edu. To reach Ning Wang, e-mail nwangrw@illinois.edu.

The paper, "Soft Substrates Promote Homogeneous Self-renewal of Embryonic Stem Cells via Downregulating Cell-matrix Tractions," is available online at http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0015655.

Soft substrate promotes pluripotent stem cell culture

2010-12-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Warning lights mark shellfish that aren't safe to eat

2010-12-16

Red tides and similar blooms can render some seafood unsafe to eat, though it can be difficult to tell whether a particular batch harbors toxins that cause food poisoning.

A new kind of marker developed by chemists at the University of California, San Diego, and reported in the journal ChemComm makes it easier to see if shellfish are filled with toxin-producing organisms.

Mussels and oysters accumulate single-celled marine creatures called dinoflagellates in their digestive systems as they filter seawater for food. Usually dinoflagellates are harmless, but sometimes ...

New method for making tiny catalysts holds promise for air quality

2010-12-16

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Fortified with iron: It's not just for breakfast cereal anymore. University of Illinois researchers have demonstrated a simpler method of adding iron to tiny carbon spheres to create catalytic materials that have the potential to remove contaminants from gas or liquid.

Civil and environmental engineering professor Mark Rood, graduate student John Atkinson and their team described their technique in the journal Carbon.

Carbon structures can be a support base for catalysts, such as iron and other metals. Iron is a readily available, low-cost catalyst ...

Researchers discover compound with potent effects on biological clock

2010-12-16

Using an automated screening technique developed by pharmaceutical companies to find new drugs, a team of researchers from UC San Diego and three other research institutions has discovered a molecule with the most potent effects ever seen on the biological clock.

Dubbed by the scientists "longdaysin," for its ability to dramatically slow down the biological clock, the new compound and the application of their screening method to the discovery of other clock-shifting chemicals could pave the way for a host of new drugs to treat severe sleep disorders or quickly reset the ...

Membership in many groups leads to quick recovery from physical challenges

2010-12-16

Los Angeles, CA (December 15, 2010) Being a part of many different social groups can improve mental health and help a person cope with stressful events. It also leads to better physical health, making you more able to withstand—and recover faster from—physical challenges, according to a study in the current Social Psychological and Personality Science (published by SAGE).

Belonging to groups, such as networks of friends, family, clubs and sport teams, improves mental health because groups provide support, help you to feel good about yourself and keep you active. But ...

Concussed high school athletes who receive neuropsychological testing sidelined longer

2010-12-16

Los Angeles, CA (December 15, 2010) When computerized neuropsychological testing is used, high school athletes suffering from a sports-related concussion are less likely to be returned to play within one week of their injury, according to a study in The American Journal of Sports Medicine (published by SAGE). Unfortunately, concussed football players are less likely to have computerized neuropsychological testing than those participating in other sports.

A total of 544 concussions were recorded by the High School Reporting Information Online surveillance system during ...

New study about Arctic sea-ice, greenhouse gases and polar bear habitat

2010-12-16

ANCHORAGE, Alaska – Sea-ice habitats essential to polar bears would likely respond positively should more curbs be placed on global greenhouse gas emissions, according to a new modeling study published today in the journal, Nature.

The study, led by the U.S. Geological Survey, included university and other federal agency scientists. The research broke new ground in the "tipping point" debate in the scientific community by providing evidence that during this century there does not seem to be a tipping point at which sea-ice loss would become irreversible.

The report ...

Meteorite just one piece of an unknown celestial body

2010-12-16

Washington, D.C.—Scientists from all over the world are taking a second, more expansive, look at the car-sized asteroid that exploded over Sudan's Nubian Desert in 2008. Initial research was focused on classifying the meteorite fragments that were collected two to five months after they were strewn across the desert and tracked by NASA's Near Earth Object astronomical network. Now in a series of 20 papers for a special double issue of the journal Meteoritics and Planetary Science, published on December 15, researchers have expanded their work to demonstrate the diversity ...

Where unconscious memories form

2010-12-16

A small area deep in the brain called the perirhinal cortex is critical for forming unconscious conceptual memories, researchers at the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain have found.

The perirhinal cortex was thought to be involved, like the neighboring hippocampus, in "declarative" or conscious memories, but the new results show that the picture is more complex, said lead author Wei-chun Wang, a graduate student at UC Davis.

The results were published Dec. 9 in the journal Neuron.

We're all familiar with memories that rise from the unconscious mind. Imagine looking ...

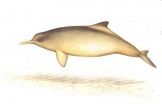

New research shows dolphin by-catch includes genetic relatives

2010-12-16

Dolphins along coast of Argentina could experience a significant loss of genetic diversity because some of the animals that accidently die when tangled in fishing nets are related. According to a new genetic analysis published this week in the journal PLoS One, Franciscana dolphins that die as by-catch are more than a collection of random individuals: many are most likely mother-offspring pairs. This result, which suggests reduced genetic diversity and reproductive potential, could have significant implications for the conservation of small marine mammals.

"It has always ...

Polar bears: On thin ice? Extinction can be averted, scientists say

2010-12-16

Polar bears were added to the threatened species list nearly three years ago when their icy habitat showed steady, precipitous decline because of a warming climate.

But it appears the Arctic icons aren't necessarily doomed after all, according to results of a study published in this week's issue of the journal Nature.

The findings indicate that there is no "tipping point" that would result in unstoppable loss of summer sea ice when greenhouse gas-driven warming rises above a certain threshold.

Scientists from several institutions, including the U.S. Geological Survey ...