The very first structures in the Universe

Astrophysicists at the Universities of Göttingen and Auckland simulate microscopic clusters from the Big Bang

2021-03-25

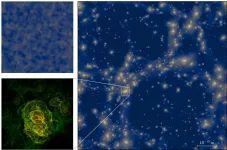

(Press-News.org) The very first moments of the Universe can be reconstructed mathematically even though they cannot be observed directly. Physicists from the Universities of Göttingen and Auckland (New Zealand) have greatly improved the ability of complex computer simulations to describe this early epoch. They discovered that a complex network of structures can form in the first trillionth of a second after the Big Bang. The behaviour of these objects mimics the distribution of galaxies in today's Universe. In contrast to today, however, these primordial structures are microscopically small. Typical clumps have masses of only a few grams and fit into volumes much smaller than present-day elementary particles. The results of the study have been published in the journal Physical Review D.

The researchers were able to observe the development of regions of higher density that are held together by their own gravity. "The physical space represented by our simulation would fit into a single proton a million times over," says Professor Jens Niemeyer, head of the Astrophysical Cosmology Group at the University of Göttingen. "It is probably the largest simulation of the smallest area of the Universe that has been carried out so far." These simulations make it possible to calculate more precise predictions for the properties of these vestiges from the very beginnings of the Universe.

Although the computer-simulated structures would be very short-lived and eventually "vaporise" into standard elementary particles, traces of this extreme early phase may be detectable in future experiments. "The formation of such structures, as well as their movements and interactions, must have generated a background noise of gravitational waves," says Benedikt Eggemeier, a PhD student in Niemeyer's group and first author of the study. "With the help of our simulations, we can calculate the strength of this gravitational wave signal, which might be measurable in the future."

It is also conceivable that tiny black holes could form if these structures undergo runaway collapse. If this happens they could have observable consequences today, or form part of the mysterious dark matter in the Universe. "On the other hand," says Professor Easther, "If the simulations predict black holes form, and we don't see them, then we will have found a new way to test models of the infant Universe."

INFORMATION:

Original publication: Eggemeier B et al, Formation of inflation halos after inflation. Physical Review D (2021). DoI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.103.063525

Contact:

Benedikt Eggemeier

University of Göttingen

Institute for Astrophysics

Friedrich-Hund-Platz 1, 37077 Göttingen

Email: benedikt.eggemeier@phys.uni-goettingen.de

http://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/617598.html

Professor Jens Niemeyer

University of Göttingen

Institute for Astrophysics

Friedrich-Hund-Platz 1, 37077 Göttingen

Email: jens.niemeyer@phys.uni-goettingen.de

http://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/617598.html

Professor Richard Easther

University of Auckland

Department of Physics

38 Princes Street Auckland, New Zealand

Email: r.easther@auckland.ac.nz

https://www.physics.auckland.ac.nz/people/reas725

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-25

One-third of the Earth's surface is covered by more than 11,000 grass species -- including crops like wheat, corn, rice and sugar cane that account for the bulk of the world's agricultural food production and important biofuels. But grass is so common that few people realize how diverse and important it really is.

Research published today in the journal Nature provides insights that scientists could use not only to improve crop design but also to more accurately model the effects of climate change. It also offers new clues that could help scientists use ...

2021-03-25

Orthopaedic researchers are one step closer to preventing life-long arm and leg deformities from childhood fractures that do not heal properly.

A new study led by the University of South Australia and published in the journal Bone, sheds light on the role that a protein plays in this process.

Lead author Dr Michelle Su says that because children's bones are still growing, an injury to the growth plate can lead to a limb in a shortened position, compared to the unaffected side.

"Cartilage tissue near the ends of long bones is known as the growth plate that is responsible for bone growth in children and, unfortunately, 30 per cent of childhood and teen fractures involve this growth ...

2021-03-25

Researchers have used the evidence of pumice from an underwater volcanic eruption to answer a long-standing mystery about a mass death of migrating seabirds.

New research into the mass death of millions of shearwater birds in 2013 suggests seabirds are eating non-food materials including floating pumice stones, because they are starving, potentially indicating broader health issues for the marine ecosystem.

The research which was led by CSIRO, Australia's national science agency, and QUT, was published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series, that examined a 2013 seabird "wreck" in which up to 3 million ...

2021-03-25

A coordinated global effort to reduce the production of greenhouse gas emissions from industry and other sectors may not stop climate change, but Earth has a powerful ally that humans might partner with to achieve carbon neutrality: Mother Nature. An international team of researchers called for the use of natural climate solutions to help "cancel" produced emissions and remove existing emissions as part of a comprehensive plan to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius -- the point at which damage to human life and livelihoods could become catastrophic, according to the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The researchers published their invited views on March 24 in ...

2021-03-25

Recently, the team led by Professor WU Changzheng from School of Chemistry and Materials Science from University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) in cooperation with the team led by Prof. WU Hengan from School of Engineering Science, realized the homogenization of surface active sites of heterogeneous catalyst by dissolving the electrocatalytic active metal in molten gallium. The related results have been published on the Nature Catalysis on March 11th.

Due to the existence of various defects and crystal faces, the active components on the surface of heterogeneous catalysts are often in different ...

2021-03-25

Tsukuba, Japan - Physical exercise has long been prescribed as a way to improve the quality of sleep. But now, researchers from Japan have found that even when exercise causes objectively measured changes in sleep quality, these changes may not be subjectively perceptible.

In a study published this month in Scientific Reports, researchers from the University of Tsukuba have revealed that vigorous exercise was able to modulate various sleep parameters associated with improved sleep, without affecting subjective reports regarding sleep quality.

Exercise is ...

2021-03-25

Lugano, Switzerland; Denver, CO, USA, 25 March 2021 - Clinical activity with a second drug inhibiting KRASG12C confirms its role as a therapeutic target in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harbouring this mutation, according to results from a study with the KRASG12C inhibitor adagrasib reported at the European Lung Cancer Virtual Congress 2021. (1)

"As we strive to identify the oncogenic driver in more and more of our patients with NSCLC, it becomes critical that we develop therapies that can target these identified oncogenic drivers," said lead author Gregory Riely, from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, ...

2021-03-25

For the first time, activation of nuclear receptor coactivator 3 (NCOA3) has been shown to promote the development of melanoma through regulation of ultraviolet radiation (UVR) sensitivity, cell cycle progression and circumvention of the DNA damage response. Results of a pre-clinical study led by Mohammed Kashani-Sabet, M.D., Medical Director of the Cancer Center at Sutter's California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC) in San Francisco, CA were published online today in Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

"Our research suggests a previously unreported mechanism by which NCOA3 regulates the DNA damage response and acts as a potential therapeutic target in melanoma, whereby activation ...

2021-03-25

Durham, NC - Depletion of a certain type of stem cell in the womb lining during pregnancy could be a significant factor behind miscarriage, according to a study released today in STEM CELLS. The study, by researchers at Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry, England, reports on how recurrent pregnancy loss is a result of the loss of decidual precursor cells prior to conception.

"This raises the possibility that they can be harnessed to prevent pregnancy disorders," said corresponding author Jan J. Brosens, M.D., Ph.D., professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Warwick Medical School (WMS).

The womb lining - or endometrium - is a ...

2021-03-25

Perhaps the best hope for slowing climate change - capturing and storing carbon dioxide emissions underground - has remained elusive due in part to uncertainty about its economic feasibility.

In an effort to provide clarity on this point, researchers at Stanford University and Carnegie Mellon University have estimated the energy demands involved with a critical stage of the process. (Watch video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZPIwwQs9aM)

Their findings, published April 8 in Environmental Science & Technology, suggest that managing and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] The very first structures in the Universe

Astrophysicists at the Universities of Göttingen and Auckland simulate microscopic clusters from the Big Bang