(Press-News.org) An analysis of adult human brain tissue reveals over 900 proteins tied to epilepsy. The brain disorder, estimated to afflict more than 3 million Americans, is mostly known for symptoms of hallucinations, dreamlike states, and uncontrolled, often disabling bodily seizures.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the study examined molecular differences among the brains of 14 epilepsy patients and another group of 14 adults of similar age and gender who did not have the disease.

Study results showed that altered levels of brain proteins predominated in the hippocampus, a structure located deep inside the skull and responsible for memory and learning. However, some 134 proteins were significantly changed in both the hippocampus and frontal cortex, the front third of the brain, which is also responsible for controlling thought and body movements. Most of the changed proteins were tied to genes in charge of protein production and linked to epilepsy in much smaller, earlier studies, but four of the 20 most-altered proteins had never previously been associated with the disorder.

One particular protein, researchers say, stood out as the most significantly depleted across all brain regions. Called G Protein Subunit 1, or GNB1, the protein is known to play an important role in dozens of biological reactions, or pathways, involved in nerve growth and communication throughout the brain, but they say its precise role in epilepsy remains unclear.

Despite decades of research, researchers say, the causes of epilepsy remains unknown. Dozens of drugs are used to control seizures by targeting known protein weaknesses, excesses, or deficiencies, and the "electrical storms" they trigger in the brain, but fail in one-third of patients to do so.

Publishing in the journal Brain Communications online March 9, the new investigation focused on regions of the frontal cortex and hippocampus that previous imaging and neurological studies had identified as most impacted by seizures.

"Our analysis identifies hundreds of potential new treatment targets for epilepsy, focusing on areas of the brain mostly damaged by the disease," says study co-senior investigator Orrin Devinsky, MD, a professor in the departments of Neurology, Neuroscience and Physiology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry at NYU Langone Health.

"While our results point to the hippocampus as the brain region most vulnerable in epilepsy, further research is needed to confirm if this region is the primary source of the illness from which damage spreads out across other brain regions, as well as how epilepsy is mutually tied to other disorders, such as dementia and depression," says Devinsky, who also serves as director of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at NYU Langone.

"Of particular interest, these findings suggest that the G Protein Subunit 1 brain pathways are a strong target for new epilepsy therapies," says study co-senior author Thomas Wisniewski, MD.

Wisniewski, the Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman Professor in the Department of Neurology and director of the Center for Cognitive Neurology at NYU Langone, says GNB1 pathways are already the target of more than a dozen drugs, such as nabilone and prazosine, used to treat conditions other than epilepsy, including nausea and high blood pressure.

Wisniewski says the NYU Langone team has plans to create a database that depicts "the brain landscape" of epilepsy protein and gene targets. They also plan initial clinical studies to determine how existing GNB1-altering medications may prevent or treat the disorder.

INFORMATION:

Funding for the study was provided by National Institutes of Health grants U01 NS090415, P30 AG066512, P01 AG060882, and S10 OD010582. Additional funding support was provided by the Bluesand Foundation and the Philippe Chatrier Foundation.

In addition to Devinsky and Wisniewski, other NYU Langone researchers included study lead investigators Geoffrey Pires, PhD; and Dominique Leitner, PhD; as well as study co-investigators Eleanor Drummond, PhD; Evgeny Kanshin, PhD; Shruti Nayak, PhD; Manor Askenazi, PhD; Arline Faustin, MD; Daniel Friedman, MD; Ludovic Debure, BS; and Beatrix Ueberheide, PhD.

Media Inquiries:

David March

212-404-3528

david.march@nyulangone.org

Researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Francis Crick Institute have developed a mass spectrometry-based technique capable of measuring samples containing thousands of proteins within just a few minutes. It is faster and cheaper than a conventional blood count. To demonstrate the technique's potential, the researchers used blood plasma collected from COVID-19 patients. Using the new technology, they identified eleven previously unknown proteins which are markers of disease severity. The work has been published in Nature Biotechnology*.

Thousands of proteins are active inside the human body at any given time, providing its structure and enabling reactions which are essential to life. The body raises and lowers the activity ...

Expectant women are more likely to give birth early if they have high blood levels of a chemical used in flame retardants compared with those who have limited exposure, a new study finds.

These polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) are used in the manufacture of furniture, carpeting, and other products to reduce flammability. Previous studies have found that the substances can leach into household dust and build up in the body where they may interfere with the thyroid, an organ that secretes brain-developing hormones. Childhood exposure to PBDEs has been linked to learning disabilities, autistic ...

Millions of years ago, aphid-like insects called whiteflies incorporated a portion of DNA from plants into their genome. A Chinese research team, publishing March 25th in the journal Cell, reveals that whiteflies use this stolen gene to degrade common toxins plants use to defend themselves against insects, allowing the whitefly to feed on the plants safely.

"This seems to be the first recorded example of the horizontal gene transfer of a functional gene from a plant into an insect," says co-author Ted Turlings (@FARCE_lab), a chemical ecologist and entomologist ...

Octopuses are known to sleep and to change color while they do it. Now, a study publishing March 25 in the journal iScience finds that these color changes are characteristic of two major alternating sleep states: an "active sleep" stage and a "quiet sleep" stage. The researchers say that the findings have implications for the evolution of sleep and might indicate that it's possible for octopuses to experience something akin to dreams.

Scientists used to think that only mammals and birds had two sleep states. More recently, it was shown that some reptiles also show non-REM and REM sleep. A REM-like sleep state was reported ...

More than half of the opioid tablets prescribed for patients who underwent orthopaedic or urologic procedures went unused in a new study by researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Using an automated text messaging system that regularly checked in with patients on their pain and opioid use, the study also showed that most opioids are taken within the first few days following a procedure and may not be necessary to manage pain even just a week following a procedure. The study was published today in JAMA Network Open.

"Through simple text messaging we highlight a method which gives clinicians the information they need to reduce prescribing and manage ...

BOSTON - In the largest study of its kind to date, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard have found the new mRNA COVID-19 vaccines to be highly effective in producing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus in pregnant and lactating women. They also demonstrated the vaccines confer protective immunity to newborns through breastmilk and the placenta.

The study, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (AJOG), looked at 131 women of reproductive age (84 pregnant, 31 lactating and 16 non-pregnant), ...

Chronic side effects among melanoma survivors after treatment with anti-PD-1 immunotherapies are more common than previously recognized, according to a study published March 25 in JAMA Oncology.

The chronic complications, which occurred in 43% of patients, affected the joints and endocrine system most commonly, and less often involved salivary glands, eyes, peripheral nerves and other organs. These complications may be long lasting, with only 14% of cases having been resolved at last follow-up. This finding contrasted with previously reported immunotherapy-related acute complications that affected visceral organs -- including the liver, colon, lungs and kidneys -- which were effectively treated with steroids. However, the vast ...

Pregnant women who consumed the caffeine equivalent of as little as half a cup of coffee a day on average had slightly smaller babies than pregnant women who did not consume caffeinated beverages, according to a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health. The researchers found corresponding reductions in size and lean body mass for infants whose mothers consumed below the 200 milligrams of caffeine per day--about two cups of coffee--believed to increase risks to the fetus. Smaller birth size can place infants at higher risk of obesity, heart ...

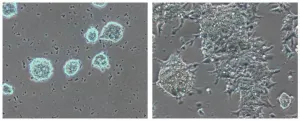

Scientists at the Proteomics Core Unit of the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), headed by Javier Muñoz, have described the mechanisms, unknown to date, involved in maintaining embryonic stem cells in the best possible state for their use in regenerative medicine. Their results, published in Nature Communications, will help to find novel stem-cell therapies for brain stroke, heart disease or neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease.

Naïve pluripotent stem cells, ideal for doing research

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are pluripotent cells that can grow ...

Quantum holds the promise of increasing the power of sensing technologies. While the field of quantum sensing has shown a lot of potential for detecting very small signals, the ability to truly optimize these sensors has been thwarted by the complexity of control schemes.

In a paper published on March 25 in Nature Partner Journals - Quantum Information, a research team based at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, explained how they applied two theoretical tools of quantum information to these types of extremely sensitive signal detection tasks. Their research suggests that honing this sensitivity to detect signals while rejecting background noise will enable the use of quantum ...