(Press-News.org) For people with tooth decay, drinking a cold beverage can be agony.

"It's a unique kind of pain," says David Clapham, vice president and chief scientific officer of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). "It's just excruciating."

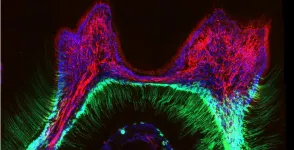

Now, he and an international team of scientists have figured out how teeth sense the cold and pinpointed the molecular and cellular players involved. In both mice and humans, tooth cells called odontoblasts contain cold-sensitive proteins that detect temperature drops, the team reports March 26, 2021, in the journal Science Advances. Signals from these cells can ultimately trigger a jolt of pain to the brain.

The work offers an explanation for how one age-old home remedy eases toothaches. The main ingredient in clove oil, which has been used for centuries in dentistry, contains a chemical that blocks the "cold sensor"protein, says electrophysiologist Katharina Zimmermann, who led the work at Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany.

Developing drugs that target this sensor even more specifically could potentially eliminate tooth sensitivity to cold, Zimmermann says. "Once you have a molecule to target, there is a possibility of treatment."

Mystery channel

Teeth decay when films of bacteria and acid eat away at the enamel, the hard, whitish covering of teeth. As enamel erodes, pits called cavities form. Roughly 2.4 billion people - about a third of the world's population - have untreated cavities in permanent teeth, which can cause intense pain, including extreme cold sensitivity.

No one really knew how teeth sensed the cold, though scientists had proposed one main theory. Tiny canals inside the teeth contain fluid that moves when the temperature changes. Somehow, nerves can sense the direction of this movement, which signals whether a tooth is hot or cold, some researchers have suggested.

"We can't rule this theory out," but there wasn't any direct evidence for it, says Clapham a neurobiologist at HHMI's Janelia Research Campus. Fluid movement in teeth - and tooth biology in general - is difficult to study. Scientists have to cut through the enamel - the hardest substance in the human body - and another tough layer called dentin, all without pulverizing the tooth's soft pulp and the blood vessels and nerves within it. Sometimes, the whole tooth "will just fall to pieces," Zimmermann says.

Zimmerman, Clapham, and their colleagues didn't set out to study teeth. Their work focused primarily on ion channels, pores in cells' membranes that act like molecular gates. After detecting a signal - a chemical message or temperature change, for example - the channels either clamp shut or open wide and let ions flood into the cell. This creates an electrical pulse that zips from cell to cell. It's a rapid way to send information, and crucial in the brain, heart, and other tissues.

About fifteen years ago, when Zimmermann was a postdoc in Clapham's lab, the team discovered that an ion channel called TRPC5 was highly sensitive to the cold. But the team didn't know where in the body TRPC5's cold-sensing ability came into play. It wasn't the skin, they found. Mice that lacked the ion channel could still sense the cold, the team reported in 2011 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

After that, "we hit a dead end," Zimmermann says. The team was sitting at lunch one day discussing the problem when the idea finally hit. "David said, 'Well, what other tissues in the body sense the cold?' Zimmermann recalls. The answer was teeth.

The whole tooth

TRPC5 does reside in teeth - and more so in teeth with cavities, study coauthor Jochen Lennerz, a pathologist from Massachusetts General Hospital, discovered after examining specimens from human adults.

A novel experimental set up in mice convinced the researchers that TRPC5 indeed functions as a cold sensor. Instead of cracking a tooth open and solely examining its cells in a dish, Zimmermann's team looked at the whole system: jawbone, teeth, and tooth nerves. The team recorded neural activity as an ice-cold solution touched the tooth. In normal mice, this frigid dip sparked nerve activity, indicating the tooth was sensing the cold. Not so in mice lacking TRPC5 or in teeth treated with a chemical that blocked the ion channel. That was a key clue that the ion channel could detect cold, Zimmermann says. One other ion channel the team studied, TRPA1, also seemed to play a role.

The team traced TRPC5's location to a specific cell type, the odontoblast, that resides between the pulp and the dentin. When someone with a a dentin-exposed tooth bites down on a popsicle, for example, those TRPC5-packed cells pick up on the cold sensation and an "ow!" signal speeds to the brain.

That sharp sensation hasn't been as extensively studied as other areas of science, Clapham says. Tooth pain may not be considered a trendy subject, he says, "but it is important and it affects a lot of people."

Zimmermann points out that the team's journey towards this discovery spanned more than a decade. Figuring out the function of particular molecules and cells is difficult, she says. "And good research can take a long time."

INFORMATION:

Because of their interactions and conflicts with the major contemporaneous civilizations of Eurasia, the Scythians enjoy a legendary status in historiography and popular culture. The Scythians had major influences on the cultures of their powerful neighbors, spreading new technologies such as saddles and other improvements for horse riding. The ancient Greek, Roman, Persian and Chinese empires all left a multitude of sources describing, from their perspectives, the customs and practices of the feared horse warriors that came from the interior lands of Eurasia.

Still, despite evidence from external sources, little is known about Scythian history. Without a written ...

'A persistent and troubling rural disadvantage'

Strategies needed to support rural Americans

CHICAGO ---Heart failure deaths are persistently higher in rural areas of the United States compared with urban areas, reports a new Northwestern Medicine study. The research also showed race disparities in heart failure are prevalent in rural and urban areas with greatest increases among Black adults under 65 years old.

Heart failure deaths have been increasing nationally since 2011, but there is significant geographic variation in these patterns based on race.

"This work demonstrates a persistent and troubling rural disadvantage with significantly higher rates of death in rural areas compared with urban areas," said lead study author Dr. Sadiya ...

University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers have identified the most toxic proteins made by SARS-COV-2--the virus that causes COVID-19 - and then used an FDA-approved cancer drug to blunt the viral protein's detrimental effects. In their experiments in fruit flies and human cell lines, the team discovered the cell process that the virus hijacks, illuminating new potential candidate drugs that could be tested for treating severe COVID-19 disease patients. Their findings were published in two studies simultaneously on March XX in Cell & Bioscience, a Springer Nature journal.

"Our work suggests there is a way to prevent SARS-COV-2 from injuring the body's tissues and doing extensive damage," says senior author of ...

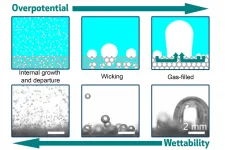

Using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen can be an effective way to produce clean-burning hydrogen fuel, with further benefits if that electricity is generated from renewable energy sources. But as water-splitting technologies improve, often using porous electrode materials to provide greater surface areas for electrochemical reactions, their efficiency is often limited by the formation of bubbles that can block or clog the reactive surfaces.

Now, a study at MIT has for the first time analyzed and quantified how bubbles form on these porous electrodes. The researchers have found that there are three different ways bubbles can form on and depart from the surface, and that these can be precisely controlled ...

Limerick, Ireland, 26 March 2020: Researchers at Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software and University of Limerick (UL), have found video gamers can significantly improve their esport skills by training for just 10 minutes a day.

The research team at Lero's Esports Science Research Lab (ESRL) at UL also found novice gamers benefited most when they wore a custom headset delivering transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) for 20 minutes before training sessions.

Dr Mark Campbell, director of Lero's Esports Science Research Lab (ESRL) and senior lecturer in sports psychology at UL, said their work showed that neurostimulation could accelerate motor performance improvements specifically in novice esports ...

Patients with lupus are more likely to have metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance - both factors linked to heart disease - if they have lower vitamin D levels, a new study reveals.

Researchers believe that boosting vitamin D levels may improve control of these cardiovascular risk factors, as well as improving long-term outcomes for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Given that photosensitivity is a key feature of SLE, the scientists say that a combination of avoiding the sun, using high-factor sunblock and living in more northerly ...

What The Study Did: Insurance claims were used to assess patterns of telehealth use across surgical specialties before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Grace F.Chao, M.D., M.Sc., of the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Michigan and Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor in Michigan, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0979)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

What The Study Did: This article discusses possible pathogenic mechanisms of brain dysfunction in patients with COVID-19.

Authors: Maura Boldrini, M.D., Ph.D., of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0500)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial ...

Bariatric surgery can significantly reduce the risk of cancer--and especially obesity-related cancers--by as much as half in certain individuals, according to a study by researchers at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School's Center for Liver Diseases and Liver Masses.

The research, published in the journal Gastroenterology, is the first to show bariatric surgery significantly decreases the risk of cancer in individuals with severe obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The risk reduction is even more pronounced in individuals with NAFLD-cirrhosis, the researchers say.

"We knew that obesity leads to certain problems, including cancer, but no one ...

The alarm bells began ringing when dozens of eagles were found dead near an Arkansas lake.

Their deaths--and, later, the deaths of other waterfowl, amphibians and fish--were the result of a neurological disease that caused holes to form in the white matter of their brains. Field and laboratory research over nearly three decades has established the primary clues needed to solve this wildlife mystery: Eagle and waterfowl deaths occur in late fall and winter within reservoirs with excess invasive aquatic weeds, and birds can die within five days after arrival.

But until recently, the toxin that caused the disease, vacuolar myelinopathy, was unknown.

Now, after years spent identifying a new toxic blue-green algal (cyanobacteria) species and isolating ...