(Press-News.org) Denver, CO, March 31, 2020 - Children with Down syndrome are 20-times more likely to develop acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) and 150-times more likely to develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML) compared to their typical peers. According to a new study by researchers at the Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome, the reason could be that children with Down syndrome are more likely to present with clonal hematopoiesis (CH), a process in which a blood stem cell acquires a genetic mutation that promotes replication.

The findings, published online by Blood Advances, add to a growing body of evidence, much of which has been established by the Crnic Institute, linking immune dysregulation to a dramatically different disease spectrum, whereby people with Down syndrome are highly predisposed to some diseases (e.g., leukemia, autoimmune disorders, and Alzheimer's disease) and highly protected from others (e.g., solid tumors).

"We found a higher-than expected rate of CH in individuals with Down syndrome between the age of one to 20 years old," says study author Dr. Alexander Liggett, who spearheaded the study as a doctoral candidate in the lab of Dr. James DeGregori, Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics. "It is a surprising finding, as the phenomenon is typically only observed in elderly people."

To perform the study, Liggett and DeGregori and colleagues applied an advanced sequencing technique they developed, called FERMI, to blood samples from the Crnic Institute Human Trisome Project BiobankTM. Not only were mutations detected more often in young individuals with Down syndrome, but those mutations were more likely to be oncogenic, or potentially cancerous. In the typical elderly population, oncogenic mutations are commonly found in the genes DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, TP53, and JAK2. Interestingly, in the Down syndrome cohort, oncogenic CH was dominated by mutations of the TET2 gene.

"Given the increased risk of leukemia that accompanies clonal expansion of blood cells carrying oncogenic mutations, these expansions may become an important biomarker of cancer risk in the future," says Dr. Liggett.

The study also found that CH in Down syndrome is associated with biosignatures of immune dysregulation that are linked to diseases that commonly co-occur with Down syndrome, including thyroiditis, Alzheimer's disease, and leukemia. This discovery opens new lines of investigation to understand how CH impacts a variety of health outcomes in Down syndrome and how to potentially counteract its effects.

"This is truly transformative. This team has identified a new trait of Down syndrome that has strong implications for understanding the appearance of comorbidities more common in this population, such as leukemia and premature ageing," said Dr. Joaquin Espinosa, Executive Director of the Crnic Institute. "The next step is to define the long-term impacts of this precocious clonal hematopoiesis and how to prevent its harmful effects."

INFORMATION:

Learn more about this important research at https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003858 and the Crnic Institute Human Trisome ProjectTM at http://www.trisome.org/.

This study builds upon generous contributions from the National Institutes of Health, the Boettcher Foundation, the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, the Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome, and the Global Down Syndrome Foundation, including funds from the Mary Miller & Charlotte Fonfara-LaRose Down Syndrome Research Fund.

About the Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome

The Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome is one of the only academic research centers fully devoted to improving the lives of people with Down syndrome through advanced biomedical research, spanning from basic science to translational and clinical investigations. Founded through the generous support and partnership of the Global Down Syndrome Foundation, the Anna and John J. Sie Foundation, and the University of Colorado, the Crnic Institute supports a thriving research program involving over 50 research teams across four campuses on the Colorado Front Range. To learn more, visit?crnicinstitute.org and follow us on social media (Facebook and Twitter @CrnicInstitute).

About Global Down Syndrome Foundation

The Global Down Syndrome Foundation (GLOBAL) is the largest non-profit in the U.S. working to save lives and dramatically improve health outcomes for people with Down syndrome. GLOBAL has donated more than $32 million to establish the first Down syndrome research institute supporting over 400 scientists and over 2,000 patients with Down syndrome from 28 states and 10 countries. Working closely with Congress and the National Institutes of Health, GLOBAL is the lead advocacy organization in the U.S. for Down syndrome research and care. GLOBAL has a membership of over 120 Down syndrome organizations worldwide and is part of a network of Affiliates - the Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome, the Sie Center for Down Syndrome, and the University of Colorado Alzheimer's and Cognition Center - all on the Anschutz Medical Campus. Visit globaldownsyndrome.org and follow us on social media (Facebook, Twitter @GDSFoundation, Instagram @globaldownsyndrome).

Press Contacts

Chelsea Donohoe, Crnic Institute

303-724-0300

chelsea.donohoe@cuanschutz.edu

Anca Call, GLOBAL

720-320-3832

anca.consultant@globaldownsyndrome.org

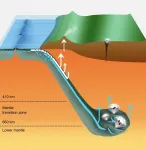

Washington, DC-- Diamonds that formed deep in the Earth's mantle contain evidence of chemical reactions that occurred on the seafloor. Probing these gems can help geoscientists understand how material is exchanged between the planet's surface and its depths.

New work published in Science Advances confirms that serpentinite--a rock that forms from peridotite, the main rock type in Earth's mantle, when water penetrates cracks in the ocean floor--can carry surface water as far as 700 kilometers deep by plate tectonic processes.

"Nearly all tectonic plates that make up the seafloor eventually bend and slide down into ...

PITTSBURGH --31 March 2021 - A detailed examination of more than 10,000 medical records at maternity clinics and hospitals in urban Malawi, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe has yielded important insight about pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in these communities as well as the frequency with which different complications occur. The findings, which were published in PLOS ONE, include data not often available or reported in much of eastern and southern Africa.

The medical chart review was undertaken by researchers from the National Institutes of Health-funded Microbicide Trials Network ...

A new study has found the first evidence of sophisticated breathing organs in 450-million-year-old sea creatures. Contrary to previous thought, trilobites were leg breathers, with structures resembling gills hanging off their thighs.

Trilobites were a group of marine animals with half-moon-like heads that resembled horseshoe crabs, and they were wildly successful in terms of evolution. Though they are now extinct, they survived for more than 250 million years -- longer than the dinosaurs.

Thanks to new technologies and an extremely rare set of fossils, scientists from UC Riverside can now show that trilobites breathed oxygen and explain how ...

March 31, 2021 - The United States is facing a persistent and worsening shortage of physicians specializing in preventive medicine, reports a study in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"The number of preventive medicine physicians is not likely to match population needs in the United States in the near term and beyond," according to the new research by Thomas Ricketts, Ph.D., MPH, and colleagues of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The study appears ...

DETROIT (March 31, 2021) - In a study that looked at racial differences in outcomes of COVID-19 patients admitted to the intensive care unit, researchers at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit found that patients of color had a lower 28-day mortality than white patients.

Race, however, was not a factor in overall hospital mortality, length of stay in the ICU or in the rate of patients placed on mechanical ventilation, researchers said.

The findings, published in Critical Care Medicine, are believed to be one of the first in the United States to study racial differences and outcomes specific to patients hospitalized ...

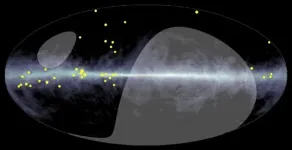

An enormous telescope complex in Tibet has captured the first evidence of ultrahigh-energy gamma rays spread across the Milky Way. The findings offer proof that undetected starry accelerators churn out cosmic rays, which have floated around our galaxy for millions of years. The research is to be published in the journal Physical Review Letters on Monday, April 5.

"We found 23 ultrahigh-energy cosmic gamma rays along the Milky Way," said Kazumasa Kawata, a coauthor from the University of Tokyo. "The highest energy among them amounts to a world record: nearly one petaelectron volt."

That's three ...

DURHAM, N.H.-- As the Biden administration announces a plan to expand the development of offshore wind energy development (OWD) along the East Coast, research from the University of New Hampshire shows significant support from an unlikely group, coastal recreation visitors. From boat enthusiasts to anglers, researchers found surprisingly widespread support with close to 77% of coastal recreation visitors supporting potential OWD along the N.H. Seacoast.

"This study takes a closer look at the lingering assumption that offshore wind in the United States might hurt coastal recreation ...

The first imaging of substantial freshwater plumes west of Hawai'i Island may help water planners to optimize sustainable yields and aquifer storage calculations. University of Hawai'i at Mānoa researchers demonstrated a new method to detect freshwater plumes between the seafloor and ocean surface in a study recently published in Geophysical Research Letters.

The research, supported by the Hawai'i EPSCoR 'Ike Wai project, is the first to demonstrate that surface-towed marine controlled-source electromagnetic (CSEM) imaging can be used to map oceanic freshwater plumes in high-resolution. It is an extension of the groundbreaking discovery of freshwater beneath the seafloor in 2020. Both are important findings in a world facing climate change, where ...

LOWELL, Mass. - Researchers studying mercury gas in the atmosphere with the aim of reducing the pollutant worldwide have determined a vast amount of the toxic element is absorbed by plants, leading it to deposit into soils.

Hundreds of tons of mercury each year are emitted into the atmosphere as a gas by burning coal, mining and other industrial and natural processes. These emissions are absorbed by plants in a process similar to how they take up carbon dioxide. When the plants shed leaves or die, the mercury is transferred to soils where large amounts also make their way into watersheds, threatening wildlife and people who eat contaminated fish.

Exposure to high levels of mercury over long ...

BRAZZAVILLE, Republic of Congo (March 31, 2021) - Researchers with the Wildlife Conservation Society's (WCS) Congo Program and the Nouabalé-Ndoki Foundation found that female putty-nosed monkeys (Cercopithecus nictitans) use males as "hired guns" to defend from predators such as leopards.

Publishing their results in the journal Royal Society Open Science, the team discovered that female monkeys use alarm calls to recruit males to defend them from predators. The researchers conducted the study among 19 different groups of wild putty-nosed monkeys, a type of forest guenon, in Mbeli Bai, a study area within the forests in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park, Northern Republic of Congo.

The results promote the idea that females' general alarm requires males to assess the nature ...