A new state of light

Physicists at the University of Bonn observe new phase in Bose-Einstein condensate of light particles

2021-04-01

(Press-News.org) A single "super photon" made up of many thousands of individual light particles: About ten years ago, researchers at the University of Bonn produced such an extreme aggregate state for the first time and presented a completely new light source. The state is called optical Bose-Einstein condensate and has captivated many physicists ever since, because this exotic world of light particles is home to its very own physical phenomena. Researchers led by Prof. Dr. Martin Weitz, who discovered the super photon, and theoretical physicist Prof. Dr. Johann Kroha have returned from their latest "expedition" into the quantum world with a very special observation. They report of a new, previously unknown phase transition in the optical Bose-Einstein condensate. This is a so-called overdamped phase. The results may in the long term be relevant for encrypted quantum communication. The study has been published in the journal Science.

The Bose-Einstein condensate is an extreme physical state that usually only occurs at very low temperatures. What's special: The particles in this system are no longer distinguishable and are predominantly in the same quantum mechanical state, in other words they behave like a single giant "superparticle". The state can therefore be described by a single wave function.

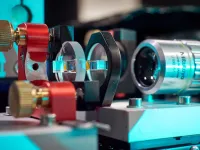

In 2010, researchers led by Martin Weitz succeeded for the first time in creating a Bose-Einstein condensate from light particles (photons). Their special system is still in use today: Physicists trap light particles in a resonator made of two curved mirrors spaced just over a micrometer apart that reflect a rapidly reciprocating beam of light. The space is filled with a liquid dye solution, which serves to cool down the photons. This is done by the dye molecules "swallowing" the photons and then spitting them out again, which brings the light particles to the temperature of the dye solution - equivalent to room temperature. Background: The system makes it possible to cool light particles in the first place, because their natural characteristic is to dissolve when cooled.

Clear separation of two phases

Phase transition is what physicists call the transition between water and ice during freezing. But how does the particular phase transition occur within the system of trapped light particles? The scientists explain it this way: The somewhat translucent mirrors cause photons to be lost and replaced, creating a non-equilibrium that results in the system not assuming a definite temperature and being set into oscillation. This creates a transition between this oscillating phase and a damped phase. Damped means that the amplitude of the vibration decreases.

"The overdamped phase we observed corresponds to a new state of the light field, so to speak," says lead author Fahri Emre Öztürk, a doctoral student at the Institute for Applied Physics at the University of Bonn. The special characteristic is that the effect of the laser is usually not separated from that of Bose-Einstein condensate by a phase transition, and there is no sharply defined boundary between the two states. This means that physicists can continually move back and forth between effects.

"However, in our experiment, the overdamped state of the optical Bose-Einstein condensate is separated by a phase transition from both the oscillating state and a standard laser," says study leader Prof. Dr. Martin Weitz. "This shows that there is a Bose-Einstein condensate, which is really a different state than the standard laser. "In other words, we are dealing with two separate phases of the optical Bose-Einstein condensate," he emphasizes.

The researchers plan to use their findings as a basis for further studies to search for new states of the light field in multiple coupled light condensates, which can also occur in the system. "If suitable quantum mechanically entangled states occur in coupled light condensates, this may be interesting for transmitting quantum-encrypted messages between multiple participants," says Fahri Emre Öztürk.

INFORMATION:

Funding:

The study received funding from the Collaborative Research Center TR 185 "OSCAR - Control of Atomic and Photonic Quantum Matter by Tailored Coupling to Reservoirs" of the Universities of Kaiserslautern and Bonn and the Cluster of Excellence ML4Q of the Universities of Cologne, Aachen, Bonn and the Research Center Jülich, funded by the German Research Foundation. The Cluster of Excellence is embedded in the Transdisciplinary Research Area (TRA) "Building Blocks of Matter and Fundamental Interactions" of the University of Bonn. In addition, the study was funded by the European Union within the project "PhoQuS - Photons for Quantum Simulation" and the German Aerospace Center with funding from the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy.

Publication: Fahri Emre Öztürk, Tim Lappe, Göran Hellmann, Julian Schmitt, Jan Klaers, Frank Vewinger, Johann Kroha & Martin Weitz: Observation of a Non-Hermitian Phase Transition in an Optical Quantum Gas. Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.abe9869

Video: https://youtu.be/PHSNJIu2IVo

Media contact:

Prof. Dr. Martin Weitz

Institut für Angewandte Physik

Universität Bonn

Tel.: +49-(0)228-73-4837

E-mail: weitz@uni-bonn.de

Dr. Julian Schmitt

Institut für Angewandte Physik

Universität Bonn

Tel.: +49-(0)228-73-60122

E-mail: schmitt@iap.uni-bonn.de

Prof. Dr. Johann Kroha

Physikalisches Insitut

Universität Bonn

Tel.: +49-(0)228-73-2798

E-mail: kroha@physik.uni-bonn.de

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-01

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) -- Despite the fact that our planet is mostly ocean and human maritime activity is more intense than it has ever been, we know remarkably little about the state of the ocean's biodiversity -- the variety and balance of species that support healthy and productive ecosystems. And it's no surprise -- marine biodiversity is complex, human impacts are uneven, and species respond differently to different stressors.

"It is really hard to know how a species is doing by just looking out from your local coast, or dipping underwater on SCUBA," said Ben Halpern, a marine ecologist at the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management at UC Santa ...

2021-04-01

The humble lab mouse has provided invaluable clues to understanding diseases ranging from cancer to diabetes to COVID-19. But when it comes to psychiatric conditions, the lab mouse has been sidelined, its rodent mind considered too different from that of humans to provide much insight into mental illness.

A new study, however, shows there are important links between human and mouse minds in how they function -- and malfunction. Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis devised a rigorous approach to study how hallucinations are produced in the brain, providing a promising entry point to the development of much-needed new therapies for schizophrenia.

The study, published April 2 in ...

2021-04-01

Tropical rainforests today are biodiversity hotspots and play an important role in the world's climate systems. A new study published today in Science sheds light on the origins of modern rainforests and may help scientists understand how rainforests will respond to a rapidly changing climate in the future.

The study led by researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) shows that the asteroid impact that ended the reign of dinosaurs 66 million years ago also caused 45% of plants in what is now Colombia to go extinct, and it made way for the reign of flowering plants in modern tropical rainforests.

"We wondered how tropical rainforests changed after a drastic ecological perturbation such as the Chicxulub impact, so we looked for tropical plant fossils," said Mónica ...

2021-04-01

LA JOLLA--(April 1, 2021) Neurons lack the ability to replicate their DNA, so they're constantly working to repair damage to their genome. Now, a new study by Salk scientists finds that these repairs are not random, but instead focus on protecting certain genetic "hot spots" that appear to play a critical role in neural identity and function.

The findings, published in the April 2, 2021, issue of Science, give novel insights into the genetic structures involved in aging and neurodegeneration, and could point to the development of potential new therapies for diseases such Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and other age-related dementia disorders.

"This research shows for the first time that ...

2021-04-01

On the afternoon of April 13, 2018, a large wave of water surged across Lake Michigan and flooded the shores of the picturesque beach town of Ludington, Michigan, damaging homes and boat docks, and flooding intake pipes. Thanks to a local citizen's photos and other data, NOAA scientists reconstructed the event in models and determined this was the first ever documented meteotsunami in the Great Lakes caused by an atmospheric inertia-gravity wave.

An atmospheric inertia-gravity wave is a wave of air that can run from 6 to 60 miles long that is created when a mass of stable air is displaced by an air mass with significantly ...

2021-04-01

In recent years, robots have gained artificial vision, touch, and even smell. "Researchers have been giving robots human-like perception," says MIT Associate Professor Fadel Adib. In a new paper, Adib's team is pushing the technology a step further. "We're trying to give robots superhuman perception," he says.

The researchers have developed a robot that uses radio waves, which can pass through walls, to sense occluded objects. The robot, called RF-Grasp, combines this powerful sensing with more traditional computer vision to locate and grasp items that might otherwise be blocked from view. The advance could one day streamline e-commerce fulfillment in warehouses or help a machine pluck a screwdriver from a jumbled toolkit.

The research will be presented in May at the IEEE International ...

2021-04-01

Plant inducible defense starts with the recognition of microbes, which leads to the activation of a complex set of cellular responses. There are many ways to recognize a microbe, and recognition of microbial features by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) outside the cell was long thought to activate the first line of defense: Pattern Triggered Immunity, or PTI. To avoid these defense responses, microbes of all kinds evolved the ability to deliver effector molecules to the plant cell, either directly into the cytoplasm or into the area just outside the cell, where they are taken up into the cytoplasm. ...

2021-04-01

New research published today in the journal Blood Advances is the first to show that restricting calories, reducing fat and sugar intake, and increasing physical activity may boost the effectiveness of chemotherapy for older children and adolescents with leukemia. This intervention, which improved chemotherapy outcomes for children being treated at two institutions, will be further studied through a national trial later this year.

B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), a cancer affecting the white blood cells in the bone marrow, is the most common type of cancer in children. In the study, researchers assessed the effects of diet and exercise on 40 individuals aged 10-21 undergoing chemotherapy at ...

2021-04-01

In some cancers, including leukemia in children and adolescents, obesity can negatively affect survival outcomes. Obese young people with leukemia are 50% more likely to relapse after treatment than their lean counterparts.

Now, a study led by researchers at UCLA and Children's Hospital Los Angeles has shown that a combination of modest dietary changes and exercise can dramatically improve survival outcomes for those with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common childhood cancer.

The researchers found that patients who reduced their calorie intake by 10% or more and adopted a moderate exercise program immediately after their diagnosis had, on average, 70% less ...

2021-04-01

For years, research to pin down the underlying cause of Alzheimer's Disease has been focused on plaque found to be building up in the brain in AD patients. But treatments targeted at breaking down that buildup have been ineffective in restoring cognitive function, suggesting that the buildup may be a side effect of AD and not the cause itself.

A new study led by a team of Brigham Young University researchers finds novel cellular-level support for an alternate theory that is growing in strength: Alzheimer's could actually be a result of metabolic dysfunction in the brain. In other words, there is growing evidence that diet and lifestyle are at the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] A new state of light

Physicists at the University of Bonn observe new phase in Bose-Einstein condensate of light particles