(Press-News.org) New research published today in the journal Blood Advances is the first to show that restricting calories, reducing fat and sugar intake, and increasing physical activity may boost the effectiveness of chemotherapy for older children and adolescents with leukemia. This intervention, which improved chemotherapy outcomes for children being treated at two institutions, will be further studied through a national trial later this year.

B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), a cancer affecting the white blood cells in the bone marrow, is the most common type of cancer in children. In the study, researchers assessed the effects of diet and exercise on 40 individuals aged 10-21 undergoing chemotherapy at Children's Hospital Los Angeles and City of Hope National Medical Center after diagnosis with high-risk B-ALL. The study dietician and physical therapist worked with the patients and their families to design low-carb, low-fat, low-sugar diet plans and moderate daily exercise regimens to meet their individual needs and preferences, as well as monitor their progress and offer ongoing family education throughout the trial. A key aim of the plans was to induce a 20% or greater caloric deficit, divided equally between reduced intake and increased calories burned.

Compared to patients in a historical control group, at the end of chemotherapy the individuals on the study's diet and exercise program were less likely to have minimal residual disease (MRD), which refers to cancer cells left in the body after treatment and is a strong predictor of eventual relapse. Notably, adherence to the diet and exercise program reduced the chances of detecting MRD after chemotherapy in all patients, regardless of their starting body weight or composition.

"This study is the first to show that we can use dietary changes to make chemotherapy work better to get rid of leukemia," said study author Etan Orgel, MD, MS, of Children's Hospital Los Angeles and the Keck School of Medicine of USC. "It is not additional pills or just one more medicine to take, and it is something any family across the world could do."

Adherence to the diet portion of the program was high: 82% of the study participants achieved a caloric deficit throughout their time on chemotherapy. Exercise adherence was not as high (31%) and researchers aim to explore this in subsequent studies. According to the research team, the relatively high participation could be attributed to the sense of empowerment felt by patients and families. "This is something they can do to contribute to their own outcomes. They have the power to harness diet and exercise as a therapy," said Dr. Orgel.

Being overweight or obese are increasingly recognized as risk factors for cancer. Preexisting obesity is associated with increased risk of developing B-ALL during childhood, and being obese when undergoing therapy for B-ALL has been tied to a greater risk for relapse and poorer survival. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that the effects of excess weight on B-ALL may be reversible. Prior to this study, the possibility of reversal had not been tested in adults or children.

While fat mass decreased only in those participants who started out as overweight or obese, patients in all weight categories showed a beneficial effect on MRD. The fact that MRD improved for all patients and did not appear to be affected by these changes in fat mass suggests that the mechanism driving the changes is not strictly fat tissue. Changes to insulin and glucose levels could be explored further in future studies, according to the researchers.

"This is a clear example of taking a scientific theory and bringing it into practice," said senior study author Steven Mittelman, MD, PhD, of UCLA Mattel Children's Hospital, who led the laboratory research that paved the way for this study. "Based on a series of early observations and animal models showing a biological connection between obesity and chemotherapy outcomes, we designed this first-of-its-kind clinical intervention. The success of the trial is a testament to that seamless interaction between bench and clinical researcher."

INFORMATION:

The researchers identified study limitations including that their participants had high rates of obesity and most identified as Hispanic (about 65% of the study population, and 83% of historical controls). They said the next step in working to understand and unravel the complex interaction between nutrition, exercise, and cancer is a national trial. They have partnered with the Therapeutic Advances in Childhood Leukemia & Lymphoma Consortium, headquartered at Children's Hospital Los Angeles, to validate their findings through a National Institutes of Health-funded prospective randomized trial, slated to begin accruing patients in summer 2021.

In some cancers, including leukemia in children and adolescents, obesity can negatively affect survival outcomes. Obese young people with leukemia are 50% more likely to relapse after treatment than their lean counterparts.

Now, a study led by researchers at UCLA and Children's Hospital Los Angeles has shown that a combination of modest dietary changes and exercise can dramatically improve survival outcomes for those with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common childhood cancer.

The researchers found that patients who reduced their calorie intake by 10% or more and adopted a moderate exercise program immediately after their diagnosis had, on average, 70% less ...

For years, research to pin down the underlying cause of Alzheimer's Disease has been focused on plaque found to be building up in the brain in AD patients. But treatments targeted at breaking down that buildup have been ineffective in restoring cognitive function, suggesting that the buildup may be a side effect of AD and not the cause itself.

A new study led by a team of Brigham Young University researchers finds novel cellular-level support for an alternate theory that is growing in strength: Alzheimer's could actually be a result of metabolic dysfunction in the brain. In other words, there is growing evidence that diet and lifestyle are at the ...

Los Angeles (April 1, 2021) -- Overweight children and adolescents receiving chemotherapy for treatment of leukemia are less successful battling the disease compared to their lean peers. Now, research conducted at the END ...

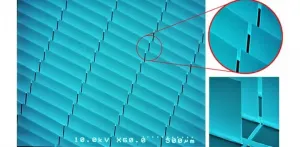

Buildings are responsible for 40 percent of primary energy consumption and 36 percent of total CO2 emissions. And, as we know, CO2 emissions trigger global warming, sea level rise, and profound changes in ocean ecosystems. Substituting the inefficient glazing areas of buildings with energy efficient smart glazing windows has great potential to decrease energy consumption for lighting and temperature control.

Harmut Hillmer et al. of the University of Kassel in Germany demonstrate that potential in "MOEMS micromirror arrays in smart windows for daylight steering," a paper published recently in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Optical Microsystems.

"Our smart glazing ...

A highly contagious SARS-CoV-2 variant was unknowingly spreading for months in the United States by October 2020, according to a new study from researchers with The University of Texas at Austin COVID-19 Modeling Consortium. Scientists first discovered it in early December in the United Kingdom, where the highly contagious and more lethal variant is thought to have originated. The journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, which has published an early-release version of the study, provides evidence that the coronavirus variant B117 (501Y) had spread across the globe undetected for months when scientists discovered it.

"By the time we learned about the U.K. variant ...

A possible explanation for why many cancer drugs that kill tumor cells in mouse models won't work in human trials has been found by researchers with The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Biomedical Informatics and McGovern Medical School.

The research was published today in Nature Communications.

In the study, investigators reported the extensive presence of mouse viruses in patient-derived xenografts (PDX). PDX models are developed by implanting human tumor tissues in immune-deficient mice, and are commonly ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: The Geological Society of America regularly publishes

articles online ahead of print. For March, GSA Bulletin topics

include multiple articles about the dynamics of China and Tibet; the ups

and downs of the Missouri River; the Los Rastros Formation, Argentina; the

Olympic Mountains of Washington State; methane seep deposits; meandering

rivers; and the northwest Hawaiian Ridge. You can find these articles at

https://bulletin.geoscienceworld.org/content/early/recent

.

Transition from a passive to active continental ...

We've all heard the adage, "If at first you don't succeed, try, try again," but new research from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh finds that it isn't all about repetition. Rather, internal states like engagement can also have an impact on learning.

The collaborative research, published in Nature Neuroscience, examined how changes in internal states, such as arousal, attention, motivation, and engagement can affect the learning process using brain-computer interface (BCI) technology. Findings suggest that changes in internal states can systematically influence how behavior improves with learning, thus paving the way ...

A study reported in the journal Current Biology on April 1 has both good news and bad news for the future of African elephants. While about 18 million square kilometers of Africa--an area bigger than the whole of Russia--still has suitable habitat for elephants, the actual range of African elephants has shrunk to just 17%of what it could be due to human pressure and the killing of elephants for ivory.

"We looked at every square kilometer of the continent," says lead author Jake Wall of the Mara Elephant Project in Kenya. "We found that 62% of those 29.2 million ...

Tokyo, Japan - Type I Diabetes Mellitus (T1D) is an autoimmune disorder leading to permanent loss of insulin-producing beta-cells in the pancreas. In a new study, researchers from The University of Tokyo developed a novel device for the long-term transplantation of iPSC-derived human pancreatic beta-cells.

T1D develops when autoimmune antibodies destroy pancreatic beta-cells that are responsible for the production of insulin. Insulin regulates blood glucose levels, and in the absence of it high levels of blood glucose slowly damage the kidneys, eyes and peripheral ...