INFORMATION:

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution. The institute furthers the understanding of tropical biodiversity and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems. Promo video.

Reference: Carvalho, M.R., Jaramillo, C., de la Parra, F., et al. 2021. Extinction at the end-Cretaceous and the origin of modern neotropical rainforests. Science.

The authors of this paper are affiliated with STRI in Panama, the Universidad del Rosario Bogota, Colombia; The Université de Montpellier, CNRS, EPHE, IRD, France; Universidad de Salamanca, Spain; the Instituto Colombiano del Petróleo, Bucaramanga, Colombia; the Chicago Botanic Garden; National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C.,; University of Florida, U.S.; Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, Brazil; ExxonMobil Corporation, Spring, Texas, U.S.; Centro Científico Tecnológico-CONICET, Mendoza, Argentina; Universidad de Chile, Santiago; University of Maryland, College Park, U.S.; Capital Normal University, Beijing, China; Corporación Geológica Ares, Bogota, Colombia; Paleoflora Ltda., Zapatoca, Colombia; University of Houston, Texas, U.S.; Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas SINCHI, Leticia, Colombia; Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín, Colombia; Boise State University, Boise, Idaho, U.S.; BP Exploration Co. Ltd., UK; and University of Fribourg, Switzerland.

Flowers!

How the chicxulub impactor gave rise to modern rainforests

2021-04-01

(Press-News.org) Tropical rainforests today are biodiversity hotspots and play an important role in the world's climate systems. A new study published today in Science sheds light on the origins of modern rainforests and may help scientists understand how rainforests will respond to a rapidly changing climate in the future.

The study led by researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) shows that the asteroid impact that ended the reign of dinosaurs 66 million years ago also caused 45% of plants in what is now Colombia to go extinct, and it made way for the reign of flowering plants in modern tropical rainforests.

"We wondered how tropical rainforests changed after a drastic ecological perturbation such as the Chicxulub impact, so we looked for tropical plant fossils," said Mónica Carvalho, first author and joint postdoctoral fellow at STRI and at the Universidad del Rosario in Colombia. "Our team examined over 50,000 fossil pollen records and more than 6,000 leaf fossils from before and after the impact."

In Central and South America, geologists hustle to find fossils exposed by road cuts and mines before heavy rains wash them away and the jungle hides them again. Before this study, little was known about the effect of this extinction on the evolution of flowering plants that now dominate the American tropics.

Carlos Jaramillo, staff paleontologist at STRI and his team, mostly STRI fellows--many of them from Colombia--studied pollen grains from 39 sites that include rock outcrops and cores drilled for oil exploration in Colombia, to paint a big, regional picture of forests before and after the impact. Pollen and spores obtained from rocks older than the impact show that rainforests were equally dominated by ferns and flowering plants. Conifers, such as relatives of the of the Kauri pine and Norfolk Island pine, sold in supermarkets at Christmas time (Araucariaceae), were common and cast their shadows over dinosaur trails. After the impact, conifers disappeared almost completely from the New World tropics, and flowering plants took over. Plant diversity did not recover for around 10 million years after the impact.

Leaf fossils told the team much about the past climate and local environment. Carvalho and Fabiany Herrera, postdoctoral research associate at the Negaunee Institute for Conservation Science and Action at the Chicago Botanic Garden, led the study of over 6,000 specimens. Working with Scott Wing at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History and others, the team found evidence that pre-impact tropical forest trees were spaced far apart, allowing light to reach the forest floor. Within 10 million years post-impact, some tropical forests were dense, like those of today, where leaves of trees and vines cast deep shade on the smaller trees, bushes and herbaceous plants below. The sparser canopies of the pre-impact forests, with fewer flowering plants, would have moved less soil water into the atmosphere than did those that grew up in the millions of years afterward.

"It was just as rainy back in the Cretaceous, but the forests worked differently." Carvalho said.

The team found no evidence of legume trees before the extinction event, but afterward there was a great diversity and abundance of legume leaves and pods. Today, legumes are a dominant family in tropical rainforests, and through associations with bacteria, take nitrogen from the air and turn it into fertilizer for the soil. The rise of legumes would have dramatically affected the nitrogen cycle.

Carvalho also worked with Conrad Labandeira at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History to study insect damage on the leaf fossils.

"Insect damage on plants can reveal in the microcosm of a single leaf or the expanse of a plant community, the base of the trophic structure in a tropical forest," Labandeira said. "The energy residing in the mass of plant tissues that is transmitted up the food chain--ultimately to the boas, eagles and jaguars--starts with the insects that skeletonize, chew, pierce and suck, mine, gall and bore through plant tissues. The evidence for this consumer food chain begins with all the diverse, intensive and fascinating ways that insects consume plants."

"Before the impact, we see that different types of plants have different damage: feeding was host-specific," Carvalho said. "After the impact, we find the same kinds of damage on almost every plant, meaning that feeding was much more generalistic."

How did the after effects of the impact transform sparse, conifer-rich tropical forests of the dinosaur age into the rainforests of today--towering trees dotted with yellow, purple and pink blossoms, dripping with orchids? Based on evidence from both pollen and leaves, the team proposes three explanations for the change, all of which may be correct. One idea is that dinosaurs kept pre-impact forests open by feeding and moving through the landscape. A second explanation is that falling ash from the impact enriched soils throughout the tropics, giving an advantage to the faster-growing flowering plants. The third explanation is that preferential extinction of conifer species created an opportunity for flowering plants to take over the tropics.

"Our study follows a simple question: How do tropical rainforests evolve?" Carvalho said. "The lesson learned here is that under rapid disturbances--geologically speaking--tropical ecosystems do not just bounce back; they are replaced, and the process takes a really long time."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How brain cells repair their DNA reveals "hot spots" of aging and disease

2021-04-01

LA JOLLA--(April 1, 2021) Neurons lack the ability to replicate their DNA, so they're constantly working to repair damage to their genome. Now, a new study by Salk scientists finds that these repairs are not random, but instead focus on protecting certain genetic "hot spots" that appear to play a critical role in neural identity and function.

The findings, published in the April 2, 2021, issue of Science, give novel insights into the genetic structures involved in aging and neurodegeneration, and could point to the development of potential new therapies for diseases such Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and other age-related dementia disorders.

"This research shows for the first time that ...

NOAA study shows promise of forecasting meteotsunamis

2021-04-01

On the afternoon of April 13, 2018, a large wave of water surged across Lake Michigan and flooded the shores of the picturesque beach town of Ludington, Michigan, damaging homes and boat docks, and flooding intake pipes. Thanks to a local citizen's photos and other data, NOAA scientists reconstructed the event in models and determined this was the first ever documented meteotsunami in the Great Lakes caused by an atmospheric inertia-gravity wave.

An atmospheric inertia-gravity wave is a wave of air that can run from 6 to 60 miles long that is created when a mass of stable air is displaced by an air mass with significantly ...

A robot that senses hidden objects

2021-04-01

In recent years, robots have gained artificial vision, touch, and even smell. "Researchers have been giving robots human-like perception," says MIT Associate Professor Fadel Adib. In a new paper, Adib's team is pushing the technology a step further. "We're trying to give robots superhuman perception," he says.

The researchers have developed a robot that uses radio waves, which can pass through walls, to sense occluded objects. The robot, called RF-Grasp, combines this powerful sensing with more traditional computer vision to locate and grasp items that might otherwise be blocked from view. The advance could one day streamline e-commerce fulfillment in warehouses or help a machine pluck a screwdriver from a jumbled toolkit.

The research will be presented in May at the IEEE International ...

Two plant immune branches more intimately connected than previously believed

2021-04-01

Plant inducible defense starts with the recognition of microbes, which leads to the activation of a complex set of cellular responses. There are many ways to recognize a microbe, and recognition of microbial features by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) outside the cell was long thought to activate the first line of defense: Pattern Triggered Immunity, or PTI. To avoid these defense responses, microbes of all kinds evolved the ability to deliver effector molecules to the plant cell, either directly into the cytoplasm or into the area just outside the cell, where they are taken up into the cytoplasm. ...

Diet and exercise may increase efficacy of chemotherapy for children with cancer

2021-04-01

New research published today in the journal Blood Advances is the first to show that restricting calories, reducing fat and sugar intake, and increasing physical activity may boost the effectiveness of chemotherapy for older children and adolescents with leukemia. This intervention, which improved chemotherapy outcomes for children being treated at two institutions, will be further studied through a national trial later this year.

B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), a cancer affecting the white blood cells in the bone marrow, is the most common type of cancer in children. In the study, researchers assessed the effects of diet and exercise on 40 individuals aged 10-21 undergoing chemotherapy at ...

Low-calorie diet and mild exercise improve survival for young people with leukemia

2021-04-01

In some cancers, including leukemia in children and adolescents, obesity can negatively affect survival outcomes. Obese young people with leukemia are 50% more likely to relapse after treatment than their lean counterparts.

Now, a study led by researchers at UCLA and Children's Hospital Los Angeles has shown that a combination of modest dietary changes and exercise can dramatically improve survival outcomes for those with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common childhood cancer.

The researchers found that patients who reduced their calorie intake by 10% or more and adopted a moderate exercise program immediately after their diagnosis had, on average, 70% less ...

New research on Alzheimer's Disease shows 'lifestyle origin at least in some degree'

2021-04-01

For years, research to pin down the underlying cause of Alzheimer's Disease has been focused on plaque found to be building up in the brain in AD patients. But treatments targeted at breaking down that buildup have been ineffective in restoring cognitive function, suggesting that the buildup may be a side effect of AD and not the cause itself.

A new study led by a team of Brigham Young University researchers finds novel cellular-level support for an alternate theory that is growing in strength: Alzheimer's could actually be a result of metabolic dysfunction in the brain. In other words, there is growing evidence that diet and lifestyle are at the ...

Diet + exercise + chemo = increased survival in youth with leukemia

2021-04-01

Los Angeles (April 1, 2021) -- Overweight children and adolescents receiving chemotherapy for treatment of leukemia are less successful battling the disease compared to their lean peers. Now, research conducted at the END ...

Smart glass has a bright future

2021-04-01

Buildings are responsible for 40 percent of primary energy consumption and 36 percent of total CO2 emissions. And, as we know, CO2 emissions trigger global warming, sea level rise, and profound changes in ocean ecosystems. Substituting the inefficient glazing areas of buildings with energy efficient smart glazing windows has great potential to decrease energy consumption for lighting and temperature control.

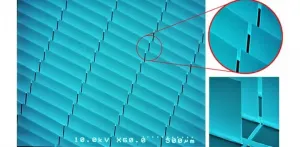

Harmut Hillmer et al. of the University of Kassel in Germany demonstrate that potential in "MOEMS micromirror arrays in smart windows for daylight steering," a paper published recently in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Optical Microsystems.

"Our smart glazing ...

Undetected coronavirus variant was in at least 15 countries before its discovery

2021-04-01

A highly contagious SARS-CoV-2 variant was unknowingly spreading for months in the United States by October 2020, according to a new study from researchers with The University of Texas at Austin COVID-19 Modeling Consortium. Scientists first discovered it in early December in the United Kingdom, where the highly contagious and more lethal variant is thought to have originated. The journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, which has published an early-release version of the study, provides evidence that the coronavirus variant B117 (501Y) had spread across the globe undetected for months when scientists discovered it.

"By the time we learned about the U.K. variant ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Jeonbuk National University researchers explore metal oxide electrodes as a new frontier in electrochemical microplastic detection

Cannabis: What is the profile of adults at low risk of dependence?

Medical and materials innovations of two women engineers recognized by Sony and Nature

Blood test “clocks” predict when Alzheimer’s symptoms will start

Second pregnancy uniquely alters the female brain

Study shows low-field MRI is feasible for breast screening

Nanodevice produces continuous electricity from evaporation

Call me invasive: New evidence confirms the status of the giant Asian mantis in Europe

Scientists discover a key mechanism regulating how oxytocin is released in the mouse brain

Public and patient involvement in research is a balancing act of power

Scientists discover “bacterial constipation,” a new disease caused by gut-drying bacteria

DGIST identifies “magic blueprint” for converting carbon dioxide into resources through atom-level catalyst design

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

[Press-News.org] Flowers!How the chicxulub impactor gave rise to modern rainforests