(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. - A devastating itching of the skin driven by severe liver disease turns out to have a surprising cause. Its discovery points toward possible new therapies for itching, and shows that the outer layer of the skin is so much more than insulation.

The finding, which appears April 2 in Gastroenterology, indicates that the keratinocyte cells of the skin surface are acting as what lead researcher Wolfgang Liedtke, MD PhD, calls 'pre-neurons.'

"The skin cells themselves are sensory under certain conditions, specifically the outermost layer of cells, the keratinocytes," said Liedtke, who is a professor of neurology at Duke School of Medicine.

This study on liver disease itching, done with colleagues in Mexico, Poland, Germany and Wake Forest University, is a continuation of Liedtke's pursuit of understanding a calcium-permeable ion channel on the cell surface called TRPV4, which he discovered 20 years ago at Rockefeller University.

The TRPV4 channel plays a crucial role in many tissues, including the sensation of pain. It was known to exist in skin cells, but nobody knew why.

"The initial ideas were that it plays a role in how the skin is layered, and in skin barrier function," Liedtke said. "But this current research is getting us into a more exciting territory of the skin actually moonlighting as a sensory organ." Once a chemical signal of itching is received, keratinocytes relay the signal to nerve endings in the skin that belong to itch-sensing nerve cells in the dorsal root ganglion next to the spine.

"Dr. Liedtke and I had a longstanding interest in the role of TRPV4 in the skin, based on our previous collaborations we decided to focus on chronic itch," said Yong Chen, and assistant professor of neurology at Duke who is first author on the study.

The researchers found that in a liver disease called primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), patients are left with a surplus of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) a phosphorylated lipid, or fat, circulating in the blood stream. They then demonstrated that LPC, injected into the skin of mice and monkeys, evokes itch.

Next they wanted to understand how this lipid could lead to the aggressive itching sensation. "If the itch comes up in PBC, it's so debilitating that the patients might need a new liver. That's how bad it can get," Liedtke said. Importantly, the skin is not chronically inflamed in PBC, meaning there is debilitating itch in the absence of chronic skin inflammation.

The researchers found that when LPC reaches the skin, the lipid can bind directly to TRPV4. Once bound, it directly activates the ion channel to open the gate for calcium ions, which are a universal switch mechanism for many cellular processes.

But in this case, the signal does something surprising. The researchers followed a signaling cascade inside the cell in which one molecule hands off to another, resulting in the formation of a tiny bubble back on the skin cell's surface called a vesicle. Vesicles are designed to bud off cells and carry whatever is inside them away.

In this case, the bubbles contained something surprising: micro-RNA, and it functioned as a signaling molecule. "This is crazy, because microRNAs are normally known to be gene regulators." Liedtke said.

It turns out that this particular bit of microRNA is itself the signal that evokes the itch.

Once they had identified it as microRNA miR-146a, the researchers injected the molecule by itself into mice and monkeys and found that it immediately caused itching, not hours later, as it would if it were regulating genes.

"Future research will address which specific itch sensory neurons respond to miR-146a, beyond the TRPV1-dependent signaling that we have found, also its in-depth mechanism," Chen said.

With the help of German and Polish liver specialists who have blood collections and itch data on PBC patients, the researchers discovered that the blood levels of microRNA-146a corresponded to itch severity, as did the LPC levels.

Knowing all the parts of the signaling that leads from excess phospho-lipid, LPC, to intolerable itching gives scientists a new way to look for advanced liver disease markers, Liedtke said.

And it points to new avenues for treating the itch, either by possibly desensitizing the TRPV4 channels in skin with a topical treatment, attacking the specific microRNAs that drive the itch, or targeted depletion of LPC.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (DE018549, K12DE022793, R01DE027454), the Michael Ross Haffner Foundation (Charlotte, NC), Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA)-Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT) (IN200720); Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) (A1-S-8760) and Secretaría de Educación, Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación del Gobierno de la Ciudad de México (SECTEI/208/2019).

CITATION: "Epithelia-Sensory Neuron Crosstalk Underlies Cholestatic Itch Induced by Lysophosphatidylcholine," Yong Chen, Zi-Long Wang, Michele Yeo, Qiao-Juan Zhang, Ana E. López-Romero, Hui-Ping Ding, Xin Zhang, Qian Zeng, Sara L. Morales-Lázaro, Carlene Moore, Ying-Ai Jin, Huang-He Yang, Johannes Morstein, Andrey Bortsov, Marcin Krawczyk, Frank Lammert, Manal Abdelmalek, Anna Mae Diehl, Piotr Milkiewicz, Andreas E. Kremer, Jennifer Y. Zhang, Andrea Nackley, Tony E. Reeves, Mei-Chuan Ko, Ru-Rong Ji, Tamara Rosenbaum, Wolfgang Liedtke. Gastroenterology, April 2, 2021.

DOI: 0.1053/j.gastro.2021.03.049

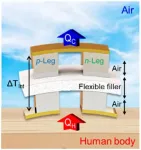

Despite the continued development and commercialization of various wearable electronic devices, such as smart bands, progress with these devices has been curbed by one major limitation, as they regularly need to be recharged. However, a new technology developed by a South Korean research team has become a hot topic, as it shows significant potential to overcome this limitation for wearable electronic devices.

The Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), or KIST, announced that a research team led by Director Jin-Sang Kim of the Jeonbuk Institute of Advanced Composite ...

A new study at Tel Aviv University reveals a possible defense mechanism developed by fireflies for protection against bats that might prey on them. According to the study, fireflies produce strong ultrasonic sounds - soundwaves that the human ear, and more importantly the fireflies themselves, cannot detect. The researchers hypothesize that these sounds are meant for the ears of bats, keeping them away from the poisonous fireflies, and thereby serving as a kind of 'musical armor'. The study was led by Prof. Yossi Yovel, Head of the Sagol School of Neuroscience, and a member of the School of Mechanical Engineering and the School of Zoology at the George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences. It was conducted in collaboration with the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST). ...

Could the next Hollywood blockbuster be written by a computer? Scientists from the University of Granada (UGR) and the University of Cádiz (UCA) have designed the world's first computer system based on artificial intelligence techniques that can help film scriptwriters create storylines with the best chance of box-office success.

The researchers focused their analysis on the "tropes" of existing films--that is, the commonplace, predictable, and even necessary clichés that repeatedly feature in film plots, based on rhetorical figures. These storytelling devices and conventions enable directors to readily convey scenarios that ...

A lot of people think regret must be a good thing because it helps you not repeat a mistake, right?

But that turns out not to be the case. Not even when it comes to casual sex, according to new research from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) Department of Psychology.

"For the most part, people continue with the same sexual behaviour and the same level of regret," says Professor Leif Edward Ottesen Kennair.

So, we repeat what we thought was a mistake, and we regret it just as much the next time around.

Professor Kennair and colleagues professor Mons Bendixen and postdoctoral ...

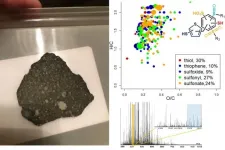

Scientists from Russia and Germany studied the molecular composition of carbonaceous chondrites - the insoluble organic matter of the Murchison and Allende meteorites - in an attempt to identify their origin. Ultra-high resolution mass spectrometry revealed a wide diversity of chemical compositions and unexpected similarities between meteorites from different groups. The research was published in the Scientific Reports.

Carbonaceous chondrites contain nearly the entire spectrum of organic molecules encountered on Earth, including nucleic acids which might have played a pivotal role in the origin of life. Since the majority of modern meteorites are of nearly the same age ...

WHO Ingrid Katz, MD, MHS, Associate Physician, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital; lead author of a new Perspective piece published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

WHAT While the U.S. has begun to vaccinate millions of Americans each day, COVID-19 vaccine supplies around the world remain scarce. Experts estimate that 80 percent of people in low-resource countries will not receive a vaccine in 2021. At the time of the paper's writing, the global vaccination rate was 6.7 million doses per day -- a rate at which it would take 4.6 years to achieve global herd immunity. In a new Perspective piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, Katz and colleagues highlight the need ...

A recent study of more than 2,000 companies finds that corporations feeling the pinch of financial constraints can benefit significantly from taking a more aggressive stance in their tax planning strategies. One takeaway of the finding is that tax authorities should look closely at the activities of companies facing financial constraints to make sure their tax activities don't become too aggressive.

Financial constraints aren't unusual and occur when a company can't afford to fund a project that would increase its value. Sometimes the constraints are caused by an external event - like a pandemic - that leaves companies with less income than they were anticipating. ...

Manufacturing - Mighty Mo

Oak Ridge National Laboratory scientists proved molybdenum titanium carbide, a refractory metal alloy that can withstand extreme temperature environments, can also be crack free and dense when produced with electron beam powder bed fusion. Their finding indicates the material's viability in additive manufacturing.

Molybdenum, or Mo, as well as associated alloys, are difficult to process through traditional manufacturing because of their high melting temperature, reactivity with oxygen and brittleness.

To address these shortcomings, the team formed a Mo metal matrix composite by mixing molybdenum and titanium carbide powders and used an electron beam to melt the ...

Piping plover breeding groups in the Northern Great Plains are notably connected through movements between habitats and show lower reproductive rates than previously thought, END ...

A comprehensive assessment of 12 different strategies for reducing beef production emissions worldwide found that industry can reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by as much as 50% in certain regions, with the most potential in the United States and Brazil. The study, " END ...