(Press-News.org) Scientists at UCL have used artificial intelligence (AI) to identify three new multiple sclerosis (MS) subtypes. Researchers say the groundbreaking findings will help identify those people more likely to have disease progression and help target treatments more effectively.

MS affects over 2.8 million people globally and 130,000 in the UK, and is classified into four* 'courses' (groups), which are defined as either relapsing or progressive. Patients are categorised by a mixture of clinical observations, assisted by MRI brain images, and patients' symptoms. These observations guide the timing and choice of treatment.

For this study, published in Nature Communications, researchers wanted to find out if there were any - as yet unidentified - patterns in brain images, which would better guide treatment choice and identify patients who would best respond to a particular therapy.

Explaining the research, lead author Dr Arman Eshaghi (UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology) said: "Currently MS is classified broadly into progressive and relapsing groups, which are based on patient symptoms; it does not directly rely on the underlying biology of the disease, and therefore cannot assist doctors in choosing the right treatment for the right patients.

"Here, we used artificial intelligence and asked the question: can AI find MS subtypes that follow a certain pattern on brain images? Our AI has uncovered three data-driven MS subtypes that are defined by pathological abnormalities seen on brain images."

In this study, researchers applied the UCL-developed AI tool, SuStaIn (Subtype and Stage Inference), to the MRI brain scans of 6,322 MS patients. The unsupervised SuStaIn trained itself and identified three (previously unknown) patterns.

The new MS subtypes were defined as 'cortex-led', 'normal-appearing white matter-led', and 'lesion-led.' These definitions relate to the earliest abnormalities seen on the MRI scans within each pattern.

Once SuStaIn had completed its analysis on the training MRI dataset, it was 'locked' and then used to identify the three subtypes in a separate independent cohort of 3,068 patients thereby validating its ability to detect the new MS subtypes.

Dr Eshaghi added: "We did a further retrospective analysis of patient records to see how people with the newly identified MS subtypes responded to various treatments.

While further clinical studies are needed, there was a clear difference, by subtype, in patients' response to different treatments and in accumulation of disability over time. This is an important step towards predicting individual responses to therapies."

NIHR Research Professor Olga Ciccarelli (UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology), the senior author of the study, said: "The method used to classify MS is currently focused on imaging changes only; we are extending the approach to including other clinical information.

"This exciting field of research will lead to an individual definition of MS course and individual prediction of treatment response in MS using AI, which will be used to select the right treatment for the right patient at the right time."

One of the senior authors, Professor Alan Thompson, Dean of the UCL Faculty of Brain Sciences, said: "We are aware of the limitations of the current descriptors of MS which can be less than clear when applied to prescribing treatment. Now with the help of AI and large datasets, we have made the first step towards a better understanding of the underlying disease mechanisms which may inform our current clinical classification. This is a fantastic achievement and has the potential to be a real game-changer, informing both disease evolution and selection of patients for clinical trials."

Researchers say the findings suggest that MRI-based subtypes predict MS disability progression and response to treatment and can now be used to define groups of patients in interventional trials. Prospective research with clinical trials is required as the next step to confirm these findings.

Dr Clare Walton, Head of Research at the MS Society, said: "We're delighted to have helped fund this study through our work with the International Progressive MS Alliance. MS is unpredictable and different for everyone, and we know one of our community's main concerns is how their condition might develop. Having an MRI-based model to help predict future progression and tailor your treatment plan accordingly could be hugely reassuring to those affected. These findings also provide valuable insight into what drives progression in MS, which is crucial to finding new treatments for everyone. We're excited to see what comes next."

MS is a neurological (nerve) condition and is one of the most common causes of disability in young people. It arises when the immune system mistakenly attacks the coating (myelin sheaths) that wrap around nerves in the brain and spinal cord. This results in the electrical signals, which pass messages along the nerves, to be disrupted, travel more slowly, or fail to get through at all.

Most people are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50, however the first signs of MS often start years earlier. Common early signs include tingling, numbness, a loss of balance and problems with vision, but because other conditions cause the same symptoms, it can take time to reach a definitive diagnosis.

Many patients have relapsing MS at first, a form of the disease where symptoms come and go as nerves are damaged, repaired and damaged again. But about half have a progressive form of the condition in which nerve damage steadily accumulates and causes ever worsening disability. Patients may experience tremors, speech problems and muscle stiffness or spasms, and may need walking aids or a wheelchair.

INFORMATION:

The study was carried out with researchers at: Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Canada; Harvard Medical School, USA; and VU University Medical Centre, the Netherlands.

* In present clinical guidelines, MS is currently categorised as either clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), primary-progressive MS (PPMS) or secondary progressive MS (SPMS).

HOUSTON - (April 6, 2021) - Runoff from Houston's 2016 Tax Day flood and 2017's Hurricane Harvey flood carried human waste onto coral reefs more than 100 miles offshore in the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, according to a Rice University study.

"We were pretty shocked," said marine biologist Adrienne Correa, co-author of the study in Frontiers in Marine Science. "One thing we always thought the Flower Garden Banks were safe from was terrestrial runoff and nutrient pollution. It's a jolt to realize that in these extreme events, it's not just the salt marsh or the seagrass that we need to worry about. Offshore ecosystems can be affected too."

The Flower Garden Banks sit atop several salt domes near the edge ...

Mitochondria, known as the powerhouses within human cells, generate the energy needed for cell survival. However, as a byproduct of this process, mitochondria also produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). At high enough concentrations, ROS cause oxidative damage and can even kill cells. An overabundance of ROS has been connected to various health issues, including cancers, neurological disorders, and heart disease.

An enzyme called manganese superoxide dismutase, or MnSOD, uses a mechanism involving electron and proton transfers to lower ROS levels in mitochondria, thus preventing oxidative damage and maintaining cell health. More than a quarter of known enzymes also rely on electron and proton transfers to facilitate cellular activities ...

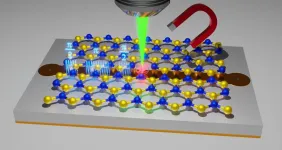

Boron nitride is a technologically interesting material because it is very compatible with other two-dimensional crystalline structures. It therefore opens up pathways to artificial heterostructures or electronic devices built on them with fundamentally new properties.

About a year ago, a team from the Institute of Physics at Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Wuerzburg in Bavaria, Germany, succeeded in creating spin defects, also known as qubits, in a layered crystal of boron nitride and identifying them experimentally.

Recently, the team led by Professor ...

Misinformation about COVID-19 is spreading from the United States into Canada, undermining efforts to mitigate the pandemic. A study led by McGill University shows that Canadians who use social media are more likely to consume this misinformation, embrace false beliefs about COVID-19, and subsequently spread them.

Many Canadians believe conspiracy theories, poorly-sourced medical advice, and information trivializing the virus--even though news outlets and political leaders in the country have generally focused on providing reliable scientific information. How then, is misinformation spreading so rapidly?

"A lot of Canadians are struggling to understand COVID-19 denialism and anti-vaccination attitudes among their loved ones," says ...

New York, NY--April 6, 2021--The digital revolution is built on a foundation of invisible 1s and 0s called bits. As decades pass, and more and more of the world's information and knowledge morph into streams of 1s and 0s, the notion that computers prefer to "speak" in binary numbers is rarely questioned. According to new research from Columbia Engineering, this could be about to change.

A new study from Mechanical Engineering Professor Hod Lipson and his PhD student Boyuan Chen proves that artificial intelligence systems might actually reach higher levels of performance if they are programmed with sound files of human language rather than with numerical data labels. The researchers discovered that in a side-by-side comparison, a neural network whose "training labels" consisted ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Exposure to phthalates, a class of chemicals widely used in packaging and consumer products, is known to interfere with normal hormone function and development in human and animal studies. Now researchers have found evidence linking pregnant women's exposure to phthalates to altered cognitive outcomes in their infants.

Most of the findings involved slower information processing among infants with higher phthalate exposure levels, with males more likely to be affected depending on the chemical involved and the order of information presented to the infants.

Reported in the journal Neurotoxicology, the study ...

The global movement of goods and people, in its modern form, has many unwanted side effects. One of these is that animal and plant species travel around the world with it. Often they fail to establish themselves in the ecosystems of the destination areas. Sometimes, however, due to a lack of effective management, they multiply to such an extent in the new environment that they become a threat to the entire ecosystem and economy. Thousands of alien species are currently documented worldwide. A quarter of them are in highly vulnerable, aquatic habitats.

So far, research has mainly focused on the ecological consequences of these invasions. In a first global data analysis, 20 scientists from 13 countries led by GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel have now compiled the economic ...

Researchers from Columbia University and Georgetown University published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that examines how consumers can adopt a sustainable consumption lifestyle by purchasing durable high-end and luxury products.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "Buy Less, Buy Luxury: Understanding and Overcoming Product Durability Neglect for Sustainable Consumption" and is authored by Jennifer Sun, Silvia Bellezza, and Neeru Paharia.

What do luxury products and sustainable goods have in common? Luxury goods possess a unique, sustainable trait that gives them a longer lifespan than lower-end products.

Sustainable consumption is on the rise with all consumers. However, younger millennial ...

BOSTON - A gene called KRAS is one of the most commonly mutated genes in all human cancers, and targeted drugs that inhibit the protein expressed by mutated KRAS have shown promising results in clinical trials, with potential approvals by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration anticipated later this year. Unfortunately, cancer cells often develop additional mutations that make them resistant to such targeted drugs, resulting in disease relapse. Now researchers led by a team at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have identified the first resistance mechanisms that may occur to these drugs and identified strategies to overcome them. The findings are published in END ...

With over 70% of respondents to a AAA annual survey on autonomous driving reporting they would fear being in a fully self-driving car, makers like Tesla may be back to the drawing board before rolling out fully autonomous self-driving systems. But new research from Northwestern University shows us we may be better off putting fruit flies behind the wheel instead of robots.

Drosophila have been subjects of science as long as humans have been running experiments in labs. But given their size, it's easy to wonder what can be learned by observing them. Research published today in the journal Nature Communications demonstrates that fruit flies use decision-making, learning and memory to perform simple functions like escaping heat. And researchers are using ...