(Press-News.org) The full assembly of human chromosome 8 is reported this week in Nature. While on the outside this chromosome looks typical, being neither short nor long or distinctive, its DNA content and arrangement are of interest in primate and human evolution, in several immune and developmental disorders, and in chromosome sequencing structure and function generally.

This linear assembly is a first for a human autosome - a chromosome not involved in sex determination. The entire sequence of chromosome 8 is 146,259,671 bases. The completed assembly fills in the gap of more than 3 million bases missing from the current reference genome.

The Nature paper is titled "The structure, function and evolution of a complete chromosome 8."

One of several intriguing characteristics of chromosome 8 is a fast-evolving region, where the mutation rate appears to be highly accelerated in humans and human-like species, in contrast to the rest of the human genome.

While chromosome 8 offers some insights into evolution and human biology, the researchers point out that the complete assembly of all human chromosomes would be necessary to acquire a fuller picture.

An international team of scientists collaborated on the chromosome 8 assembly and analysis. The lead author of the paper is Glennis Logsdon, a postdoctoral fellow in genome sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

The senior author is Evan Eichler, professor of genome sciences at the UW School of Medicine and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. His group is noted for developing better methods for sequencing DNA and for analyzing mutational trends that may be important in research on primate evolution and neurological disorders.

In addition to the human chromosome 8 assembly, the project researchers also created high quality draft assemblies of the linking site at the waist of the chromosome, the centromere, in the chimpanzee, orangutan and macaque. The data allowed the scientists to begin to chart the evolutionary history of the chromosome 8 centromere.

Almost like inspecting the depths of a geological site, the researchers observed, on a molecular scale, a layered, mirrored symmetry in how this centromere structure evolved from great ape ancestors. More ancient parts were pushed to the periphery, similar to making room for new material in the middle of a factory production line.

Other research institutions involved in the chromosome 8 assembly project include the Development Therapeutics Branch of the National Cancer Institute, the Genome Informatics Section of the National Human Genome Research Institute, the University of Bari, Italy; the Center for Algorithmic Biology at St. Petersburg State University, Russia; University of California, San Diego, Washington University in St. Louis, University of Pittsburgh, and the University of California, Santa Cruz. Data were also generated with Oxford Nanopore Technologies and Pacific Biosciences long-read sequencing to resolve gaps in the telomere-to-telomere, or end-to-end, assembly of the chromosome.

Earlier research by a number of scientists had pointed to regions of chromosome 8 as being important both in the normal formation of the brain, as well as to some developmental variations, such as small head size or skull and facial differences. Mutations on this chromosome have also been implicated in some heart defects, certain forms of cancer, premature aging syndromes, immune responses, and immune disorders like psoriasis and Crohn's disease.

However, the full sequencing of this and most other human chromosomes could not be attempted until recently because the technology and methods to wade through large areas of duplication and identical repeats had not become available. Putting together the puzzle accurately from short reads of DNA, for instance, would have been extremely difficult.

The chromosome 8 assembly achievement benefited from advances in long-read technologies, as well as from the availability of DNA material from hydatidiform moles. These are rare, abnormal growths in the placenta.

The full sequencing of chromosome 8 now provides information that might improve, for example, the understanding of what predisposes specific parts of the chromosome's DNA to microdeletions suspected in certain forms of developmental delay, brain and heart malformations, and autoimmune problems.

The researchers were also able to obtain more information on a part of chromosome 8 that contains some of the greatest copy-number variability among people. The repeat unit can vary from 53 to 326 copies.

With the chromosome 8 assembly finished, researchers look forward to the world scientific community completing other human chromosome assemblies, and to new challenges in applying what has been learned to further studies of human genome sequencing.

INFORMATION:

The researchers on this study declare no competing financial interests.

Using DNA structures as scaffolds, Tim Liedl, a scientist of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich, has shown that precisely positioned gold nanoparticles can serve as efficient energy transmitters.

Since the inception of the field in 2006, laboratories around the world have been exploring the use of 'DNA origami' for the assembly of complex nanostructures. The method is based on DNA strands with defined sequences that interact via localized base pairing. "With the aid of short strands with appropriate sequences, we can connect specific regions of long DNA molecules together, rather like forming three-dimensional structures by folding a flat sheet of paper in certain ...

It's like something out of science fiction. Research led by Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences has revealed that a group of microbes, which feed off chemical reactions triggered by radioactivity, have been at an evolutionary standstill for millions of years. The discovery could have significant implications for biotechnology applications and scientific understanding of microbial evolution.

"This discovery shows that we must be careful when making assumptions about the speed of evolution and how we interpret the tree of life," said Eric Becraft, the lead author on the paper. "It is possible that some organisms go into an evolutionary ...

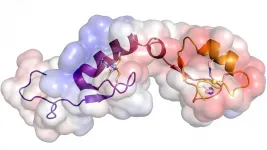

Design, synthesis, molecular modeling, and biological evaluation of acrylamide derivatives as potent inhibitors of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

Human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) is a viable target for the development of therapeutics to treat cancer and immunological diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis and multiple sclerosis (MS).

The authors designed and synthesized a series of acrylamide-based novel DHODH inhibitors as potential RA treatment agents. 2-Acrylamidobenzoic acid analog 11 was identified as the lead compound for structure-activity ...

Orchids of the Boreal zone are rare species. Most of the 28,000 species of the Orchid family actually live in the tropics. In the Boreal zone, ground orchids can hardly tolerate competition from other plants -- mainly forbs or grasses. So they are often pushed into ecotones -- border areas between meadows and forests, or between forests and swamps.

Furthermore, there has been a decline in wild orchids all over North America and Eurasia, caused in part by human-induced destruction of their habitats, the transformation of ecosystems, and the harvesting of flowers from the wild.

In the Novosibirsk region, ...

Pioneering research led by experts from the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute has provided new insight into formation of the human embryo.

The team of researchers discovered an unique regenerative property of cells in the early human embryo.

The first tissue to form in the embryo of mammals is the trophectoderm, which goes on to connect with the uterus and make the placenta. Previous research in mice found that trophectoderm is only made once.

In the new study, however, the research team found that human early embryos are able to regenerate trophectoderm. They also showed that human embryonic stem cells grown in the laboratory can similarly ...

Every year, our planet encounters dust from comets and asteroids. These interplanetary dust particles pass through our atmosphere and give rise to shooting stars. Some of them reach the ground in the form of micrometeorites. An international program conducted for nearly 20 years by scientists from the CNRS, the Université Paris-Saclay and the National museum of natural history with the support of the French polar institute, has determined that 5,200 tons per year of these micrometeorites reach the ground. The study will be available in the journal Earth & Planetary Science Letters from April 15.

Micrometeorites have always fallen on our planet. These interplanetary dust particles from comets or asteroids are particles of a few tenths to hundredths of a millimetre that have passed ...

Scientists have made a pivotal breakthrough in understanding the way in which cells communicate with each other.

A team of international researchers, including experts from the University of Exeter's Living Systems Institute, has identified how signalling pathways of Wnt proteins - which orchestrate and control many cell developmental processes - operate on both molecular and cellular levels.

Various mechanisms exist for cells to communicate with each other, and many are essential for development. This information exchange between cells is often based on signalling proteins that activate specific intracellular signalling cascades to control cell behaviour at a distance.

Wnt proteins are produced by a relatively small group ...

The damaging effects of life under Nazi rule have long been known with many victims having experienced periods of protracted emotional and physical torture, malnutrition and mass exposure to disease. But recent research from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem show that even for those who survived, their health and mortality continued to be directly impacted long after the end of the Holocaust.

The study, led by Drs. Iaroslav Youssim and Hagit Hochner from the School of Public Health at the Faculty of Medicine and published in the American Journal of Epidemiology, investigated mortality rates from ...

Short pieces of DNA--jumping genes--can bounce from one place to another in our genomes. When too many DNA fragments move around, cancer, infertility, and other problems can arise. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor & HHMI Investigator Leemor Joshua-Tor and a research investigator in her lab, Jonathan Ipsaro, study how cells safeguard the genome's integrity and immobilize these restless bits of DNA. They found that one of the jumping genes' most needed resources may also be their greatest vulnerability.

The mammalian genome is full of genetic elements that have the potential to move from place to place. One type is an LTR retrotransposon (LTR). In normal cells, these elements don't ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Research shows people turn to religion in times of fear and uncertainty - and March 2020 was one of those times.

To find the impact of religion during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Landon Schnabel, the Robert and Ann Rosenthal Assistant Professor of Sociology in the College of Arts and Sciences, analyzed responses from 11,537 Americans surveyed March 19-24, 2020, shortly after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global health pandemic.

Religion protected mental health of members of several ...