(Press-News.org) Piping plovers, charismatic shorebirds that nest and feed on many Atlantic Coast beaches, rely on different kinds of coastal habitats in different regions along the Atlantic Coast, according to a new study by the U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The Atlantic Coast and Northern Great Plains populations of the piping plover were listed as federally threatened in 1985. The Atlantic coast population is managed in three regional recovery units, or regions: New England, which includes Massachusetts and Rhode Island; Mid-Atlantic, which includes New York and New Jersey; and Southern, which includes Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina.

While the Atlantic populations are growing, piping plovers have not recovered as well in the Mid-Atlantic and Southern regions as they have in the New England region. The habitat differences uncovered by the study may be a factor in the unequal recovery.

"Knowing piping plovers are choosing different habitat for nesting up and down the Atlantic Coast is key information that resource managers can use to refine recovery plans and protect areas most needed for further recovery of the species," said Sara Zeigler, a USGS research geographer and the lead author of the study. "It will also help researchers predict how climate change impacts, such as increased storm frequency, erosion and sea-level rise, could affect habitat for this high-profile shorebird."

The researchers found that piping plovers breeding in the New England region were most likely to nest on the portion of the beach between the high-water line and the base of the dunes. By contrast, plovers in the Southern region nested farther inland in areas where storm waves have washed over and flattened the dunes - a process known as 'overwash.' In the Mid-Atlantic region plovers used both habitats but tended to select overwash areas more frequently.

In general, overwash areas tend to be less common than backshore -- shoreline to dunes -- habitats. Nesting pairs that rely on overwash features, such as those in the Mid-Atlantic and Southern regions, have more limited habitat compared to birds in New England that have adapted to nesting in backshore environments.

The authors suggest that the differences in nesting habitat selection may be related to the availability of quality food. Piping plover chicks, which cannot fly, must be able to access feeding areas on foot. In New England, piping plovers can find plenty of food along the ocean shoreline, so they may have more options for successful nesting. However, ocean shorelines along the Southern and Mid-Atlantic regions may not provide enough food, forcing adults and chicks to move towards bay shorelines on the interiors of barrier islands to feed. This would explain why so many nests in these regions occurred in overwash areas, which are scarcer than backshore areas but tend to provide a clear path to the bay shoreline.

In all three regions, plovers most often chose to nest in areas with sand mixed with shells and with sparse plant life. These materials match the species' sandy, mottled coloring and help the birds blend into the environment, enhancing the camouflage that is their natural defense against predators. Piping plover adults may avoid dense vegetation because it may impede their ability to watch for foxes, raccoons, coyotes and other predators.

The U.S. Atlantic Coast population of piping plovers increased from 476 breeding pairs when it was listed in 1985 to 1,818 pairs in 2019, according to the USFWS. The population increased by 830 breeding pairs in New England but only 349 and 163 pairs in the Mid-Atlantic and Southern regions respectively.

"This study will help us tailor coastal management recommendations in each region," said Anne Hecht, a USFWS endangered species biologist and a co-author of the paper. "We are grateful to the many partners who collected data for this study, which will help us be more effective in our efforts to recover the plover population."

"This research will fuel further studies on piping plovers, their habitat-use and food resources," Zeigler added. "Refining the models used in this research will help researchers predict habitat availability with future changes in shorelines, sea level and beach profiles."

INFORMATION:

The researchers wish to thank the many partners who contributed data used in this research, including the USFWS, National Park Service, The Nature Conservancy, Massachusetts Audubon Society, Virginia Tech, New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife, Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey and Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries.

Read the article in Ecosphere: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ecs2.3418

WHAT:

The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting people with or at risk for HIV both indirectly, by interfering with HIV treatment and prevention services, and directly, by threatening individual health. An effective response to these dual pandemics requires unprecedented collaboration to accelerate basic and clinical research, as well as implementation science to expeditiously introduce evidence-based strategies into real-world settings. This message comes from a review article co-authored by Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Health, and colleagues published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

By disrupting critical health care services, the COVID-19 pandemic threatens ...

April 8, 2021 - Routinely collected data on patients undergoing spinal fusion surgery do not provide a valid basis for assessing and comparing hospital performance on patient safety outcomes, reports a study in Spine. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

At a time when hospitals are increasingly subject to online rankings or "pay-for-performance" reimbursement programs, metrics based on hospital administrative data are "unreliable for profiling hospital performance," concludes the new research by Jacob K. Greenberg, MD, MSCI, of Washington University in St Louis and colleagues. ...

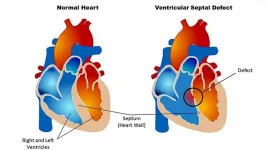

In a medical records study covering thousands of children, a U.S.-Canadian team led by researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine concludes that while surgery to correct congenital heart disease (CHD) within 10 years after birth may restore young hearts to healthy function, it also may be associated with an increased risk of hypertension -- high blood pressure -- within a few months or years after surgery. ...

Waste materials from the pulp and paper industry have long been seen as possible fillers for building products like cement, but for years these materials have ended up in the landfill. Now, researchers at UBC Okanagan are developing guidelines to use this waste for road construction in an environmentally friendly manner.

The researchers were particularly interested in wood-based pulp mill fly ash (PFA), which is a non-hazardous commercial waste product. The North American pulp and paper industry generates more than one million tons of ash annually by burning wood in ...

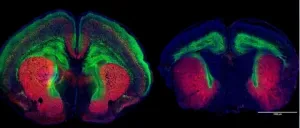

JUPITER, FL -- Damage to the autism-associated gene Dyrk1a, sets off a cascade of problems in developing mouse brains, resulting in abnormal growth-factor signaling, undergrowth of neurons, smaller-than-average brain size, and, eventually, autism-like behaviors, a new study from Scripps Research, Florida, finds.

The study from neuroscientist Damon Page, PhD, describes a new mechanism underlying the brain undergrowth seen in individuals with Dyrk1a mutations. Page's team used those insights to target the affected pathway with an existing medicine, a growth hormone. It restored normal brain growth in the Dyrk1a mutant mice, Page says.

"As of now, there's simply no targeted treatments available for individuals with autism spectrum ...

When you think of ways to treat opioid use disorder, you might think methadone clinics and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. You probably don't imagine stretches and strengthening exercises.

But Anne Swisher--professor at the West Virginia University School of Medicine--is working to address opioid misuse in an unconventional way: through physical therapy. She and her colleagues have enhanced physical therapy instruction at WVU to emphasize the profession's role in preventing and treating opioid use disorder.

"Students have different interests and passions within the profession, and they find their niche," said Swisher, a researcher and director of scholarship in the Division of Physical Therapy. "No matter what their passion is, there ...

EVANSTON, Ill. -- Five-star ratings are no guarantee to lead you to the perfect barber who truly understands your hair or to the espresso machine that brews a perfect cup of coffee.

That's because most products online are now rated positively, making it harder than ever to truly discern whether they will succeed in the marketplace.

A new study from Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management and the University of Massachusetts Boston was able to predict the success of movies, commercials, books and restaurants by relying on the "emotionality" of reviews instead of the star rating.

The researchers explored box office revenue of 2,400 movies, sales of 1.6 million books and real-world reservations at ...

Astronomers at Western University have discovered the most rapidly rotating brown dwarfs known. They found three brown dwarfs that each complete a full rotation roughly once every hour. That rate is so extreme that if these "failed stars" rotated any faster, they could come close to tearing themselves apart. Identified by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, the brown dwarfs were then studied by ground-based telescopes including Gemini North, which confirmed their surprisingly speedy rotation.

Three brown dwarfs have been discovered spinning faster than any other found before. Astronomers at Western University in Canada first measured the rotation speeds of these brown dwarfs using NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and confirmed them with follow-up ...

Taiwan is an island of extremes: severe earthquakes and typhoons repeatedly strike the region and change the landscape, sometimes catastrophically. This makes Taiwan a fantastic laboratory for geosciences. Erosion processes, for example, occur up to a thousand times faster in the center of the island than in its far south. This difference in erosion rates influences the chemical weathering of rocks and yields insights into the carbon cycle of our planet on a scale of millions of years. A group of researchers led by Aaron Bufe and Niels Hovius of the German Research Center for Geosciences (GFZ) has now taken advantage of the different erosion rates and investigated how uplift and erosion of rocks determine the balance of carbon emissions ...

Having a responsive, supportive partner minimizes the negative impacts of an individual's depression or external stress on their romantic relationship, according to research by a University of Massachusetts Amherst social psychologist.

Paula Pietromonaco, professor emerita of psychological and brain sciences, drew on data from her Growth in Early Marriage project (GEM) to investigate what she had discovered was an under-studied question. Findings are published in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science.

"I was really surprised that although there's a ton of work out there on depression, there ...