(Press-News.org) BOSTON - (April 12, 2021) - A new source of energy expending brown fat cells has been uncovered by researchers at the Joslin Diabetes Center, which they say points towards potential new therapeutic options for obesity. According to the new report, published today by Nature Metabolism, the key lies in the expression of a receptor called Trpv1 (temperature-sensitive ion channel transient receptor potential cation subfamily V member 1) -- a protein known to sense noxious stimuli, including pain and temperature.

Specifically, the authors point to smooth muscle cells expressing the Trpv1 receptor and identify them as a novel source of energy-burning brown fat cells (adipocytes). This should translate into increased overall energy expenditure - and ultimately, researchers hope, reduced weight.

Brown fat or brown adipose tissue is a distinct type of fat that is activated in response to cold temperatures. Its primary role is to produce heat to help maintain body temperature and it achieves that by burning calories. This has raised the prospect that such calorie burning can be translated into weight loss, particularly in the context of obesity.

"The capacity of brown and beige fat cells to burn fuel and produce heat, especially upon exposure to cold temperatures, have long made them an attractive target for treating obesity and other metabolic disorders," said senior author Yu-Hua Tseng . "And yet, the precise origins of cold-induced brown adipocytes and mechanisms of action have remained a bit of a mystery."

The source of these energy-burning fat cells was previously considered to be exclusively related to a population of cells that express the receptor Pdgfrα (platelet derived growth factor receptor alpha). However, wider evidence suggests other sources may exist. Identifying these other sources would then open up potential new targets for therapy that would get around the somewhat uncomfortable use of cold temperatures to try to treat obesity.

The team initially investigated the general cellular makeup of brown adipose tissue from mice housed at different temperatures and lengths of time. Notably, they employed modern single cell RNA sequencing approaches to try to identify all types of cells present. This avoided issues of potential bias towards one particular cell type - a weakness of previous studies, according to the authors.

"Single cell sequencing coupled with advanced data analysis techniques has allowed us to make predictions in silico about the development of brown fat," said co-author Matthew D. Lynes. "By validating these predictions, we hope to open up new cellular targets for metabolic research."

As well as identifying the previously known Pdgfrα-source of energy burning brown fat cells, their analysis of the single cell RNA sequencing data suggested another distinct population of cells doing the same job - cells derived from smooth muscle expressing Trpv1*. The receptor has previously been identified in a range of cell types and is involved in pain and heat sensation.

Further investigations with mouse models confirmed that the Trpv1-positive smooth muscle cells gave rise to the brown energy-burning version of fat cells especially when exposed to cold temperatures. Additional experiments also showed that the Trpv1-positive cells were a source for beige fat cells that appear in response to cold in white fat, further expanding the potential influence of Trpv1-expressing precursor cells.

"These findings show the plasticity of vascular smooth muscle lineage and expand the repertoire of cellular sources that can be targeted to enhance brown fat function and promote metabolic health," added lead author.

Brown adipose tissue is the major thermogenic organ in the body and increasing brown fat thermogenesis and general energy expenditure is seen as one potential approach to treating obesity, added Shamsi.

"The identification of Trpv1-expessing cells as a new source of cold-induced brown or beige adipocytes suggests it might be possible to refine the use of cold temperatures to treat obesity by developing drugs that recapitulate the effects of cold exposure at the cellular level," said Tseng.

The authors note that Trpv1 has a role in detecting multiple noxious stimuli, including capsaicin (the pungent component in chili peppers) and that previous studies suggest administration in both humans and animals results in reduced food intake and increased energy expenditure.

Tseng added: "Further studies are now planned to address the role of the Trpv1 channel and its ligands and whether it is possible to target these cells to increase numbers of thermogenic adipocytes as a therapeutic approach towards obesity."

INFORMATION:

Other contributors to the research include Mary Piper (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA), Li-Lun Ho (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA), Tian Lian Huang (Joslin Diabetes Center), Anushka Gupta and Aaron Streets (University of California-Berkley, CA).

Funding for the study was provided by US National Institutes of Health grants, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the American Diabetes Association. Full details are available in the Nature Metabolism report.

Shamsi et al. Vascular smooth muscle-derived TRPV1-positive progenitors are a new source of cold-induced thermogenic adipocytes. Nature Metabolism https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s42255-021-00373-z

Histones are tiny proteins that bind to DNA and hold information that can help turn on or off individual genes. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet have developed a technique that makes it possible to examine how different versions of histones bind to the genome in tens of thousands of individual cells at the same time. The technique was applied to the mouse brain and can be used to study epigenetics at a single-cell level in other complex tissues. The study is published in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

"This technique will be an important tool for examining what makes cells different from each other at the epigenetic level," says Marek ...

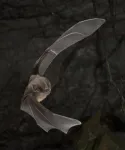

WASHINGTON--Deep in a Jamaican cave is a treasure trove of bat poop, deposited in sequential layers by generations of bats over 4,300 years.

Analogous to records of the past found in layers of lake mud and Antarctic ice, the guano pile is roughly the height of a tall man (2 meters), largely undisturbed, and holds information about changes in climate and how the bats' food sources shifted over the millennia, according to a new study.

"We study natural archives and reconstruct natural histories, mostly from lake sediments. This is the first time scientists have interpreted past bat ...

BOSTON - Exercise training may slow tumor growth and improve outcomes for females with breast cancer - especially those treated with immunotherapy drugs - by stimulating naturally occurring immune mechanisms, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Harvard Medical School (HMS) have found.

Tumors in mouse models of human breast cancer grew more slowly in mice put through their paces in a structured aerobic exercise program than in sedentary mice, and the tumors in exercised mice exhibited an increased anti-tumor immune response.

"The most exciting finding was that exercise training brought into tumors immune cells capable of killing cancer cells known as cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+ ...

Philadelphia, April 12, 2021 - Electronic cigarette (EC) use, or vaping, has both gained incredible popularity and generated tremendous controversy, but although they may be less harmful than tobacco cigarettes (TCs), they have major potential risks that may be underestimated by health authorities, the public, and medical professionals. Two cardiovascular specialists review the latest scientific studies on the cardiovascular effects of cigarette smoking versus ECs in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology, published by Elsevier. They conclude that young non-smokers should be discouraged from vaping, flavors targeted towards adolescents should be banned, and laws and regulations ...

What exactly happens when the corona virus SARS-CoV-2 infects a cell? In an article published in Nature, a team from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry paints a comprehensive picture of the viral infection process. For the first time, the interaction between the coronavirus and a cell is documented at five distinct proteomics levels during viral infection. This knowledge will help to gain a better understanding of the virus and find potential starting points for therapies.

When a virus enters a cell, viral and cellular protein molecules begin to interact. Both the replication of the virus and the reaction of ...

PHILADELPHIA - Residents in majority-Black neighborhoods experience higher rates of severe pregnancy-related health problems than those living in predominantly-white areas, according to a new study of pregnancies at a Philadelphia-based health system, which was led by researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The findings, published today in Obstetrics and Gynecology, suggest that neighborhood-level public health interventions may be necessary in order to lower the rates of severe maternal morbidity -- such as a heart attack, heart failure, eclampsia, or hysterectomy -- and mortality ...

April 12, 2021 - For critically ill COVID-19 patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), the risk of death remains high - but is much lower than suggested by initial studies, according to a report published today by Annals of Surgery. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The findings support the use of ECMO as "salvage therapy" for COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or respiratory failure who do not improve with conventional mechanical ventilatory support, according to the new research by Ninh T. Nguyen, MD, Chair of the Department of Surgery, University ...

New research by Yale Cancer Center shows patients with early-onset colorectal cancer, age 50 and younger, have a better survival rate than patients diagnosed with the disease later in life. The study was presented virtually today at the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting.

"Although small, we were surprised by our findings," said En Cheng, MD, MSPH, lead author of the study from Yale Cancer Center. "Past studies have shown younger colorectal patients, those under 50, were reported to experience worse survival compared with patients diagnosed at older ages. We hope this result can be inspiring for these ...

In a new study led by Yale Cancer Center, researchers have advanced a tumor-targeting and cell penetrating antibody that can deliver payloads to stimulate an immune response to help treat melanoma. The study was presented today at the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) virtual annual meeting.

"Most approaches rely on direct injection into tumors of ribonucleic acids (RNAs) or other molecules to boost the immune response, but this is not practical in the clinic, especially for patients with advanced cancer," said Peter M. Glazer, MD, PhD, Chair of the Department of Therapeutic Radiology ...

New research from CU Cancer Center member Scott Cramer, PhD, and his colleagues could help in the treatment of men with certain aggressive types of prostate cancer.

Published this week in the journal Molecular Cancer Research, Cramer's study specifically looks at how the loss of two specific prostate tumor-suppressing genes -- MAP3K7 and CHD1 --increases androgen receptor signaling and makes the patient more resistant to the anti-androgen therapy that is typically administered to reduce testosterone levels in prostate cancer patients.

"Doctors don't normally stratify patients based on this subtype and say, 'We're going to have to treat these people differently,' but we think this should be considered before treating ...