Scientists discover three liquid phases in aerosol particles

Findings could help explain how air pollutants interact with the atmosphere

2021-04-12

(Press-News.org) Researchers at the University of British Columbia have discovered three liquid phases in aerosol particles, changing our understanding of air pollutants in the Earth's atmosphere.

While aerosol particles were known to contain up to two liquid phases, the discovery of an additional liquid phase may be important to providing more accurate atmospheric models and climate predictions. The study was published today in PNAS.

"We've shown that certain types of aerosol particles in the atmosphere, including ones that are likely abundant in cities, can often have three distinct liquid phases." says Dr. Allan Bertram, a professor in the department of chemistry. "These properties play a role in air quality and climate. What we hope is that these results improve models used in air quality and climate change policies."

Aerosol particles fill the atmosphere and play a critical role in air quality. These particles contribute to poor air quality and absorb and reflect solar radiation, affecting the climate system. Nevertheless, how these particles behave remains uncertain. Prior to 2012, it was often assumed in models that aerosol particles contained only one liquid phase.

In 2012, researchers from the University of British Columbia and Harvard University provided the first observations of two liquid phases in particles collected from the atmosphere. More recently, researchers at UBC hypothesized three liquid phases could form in atmospheric particles if the particles consisted of low polarity material, medium polarity material, and salty water.

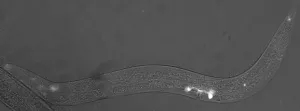

To test this, a solvatochromic dye--a dye that changes color depending on polarity of its surroundings--was injected into particles containing a mixture of all three of these components. Although the solvatochromic dye method has been used widely in biology and chemistry, it has not been used to characterize the phase behaviour of atmospheric aerosols. Remarkably, three different colors were observed in these particles, confirming the presence of three liquid phases.

Scientists were also able to study the properties of particles containing three phases, including how well these particles acted as seeds for clouds, and how fast gases go into and out of the particles.

The study focused on particles containing mixtures of lubricating oil from gas vehicles, oxidized organic material from fossil fuel combustion and trees, and inorganic material from fossil fuel combustion. Depending on the properties of the lubricating oil and the oxidized organic material, different number of liquid phases will appear resulting in different impacts on air quality and climate.

"Through what we've shown, we've improved our understanding of atmospheric aerosols. That should lead to better predictions of air quality and climate, and better prediction of what is going to happen in the next 50 years," says Dr. Bertram. "If policies are made based on a model that has high uncertainties, then the policies will have high uncertainties. I hope we can improve that."

With the urgency of climate goals, policy that is built on accurate atmospheric modelling reduces the possibility of using resources and finances toward the wrong policies and goals.

INFORMATION:

This study was led by researchers at the University of British Columbia with researchers from the University of California Irvine and McGill University.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-12

Using laboratory-grown roundworms as well as human and mouse eye tissue, University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers have identified a new potential mechanism for age-related macular degeneration--the leading cause of blindness among older adults. The UMSOM researchers say that the findings suggest a new and distinct cause that is different from the previous model of a problematic immune system, showing that the structural organization of the eye's light-detecting cells may be affected by the disease.

The discovery offers the potential to identify new molecular targets to treat the disease. Their discovery was published on April 12 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

According to the National Eye Institute, ...

2021-04-12

PRINCETON, N.J.--Increasing diversity remains a key priority at universities, especially in the wake of mass demonstrations in support of racial equality in 2020 following the death of George Floyd. Many universities are guided by the motivation that diversity enhances student learning, a rationale supported by the U.S. Supreme Court.

This approach, however, is a view preferred by white and not Black Americans, and it also aligns with better relative outcomes for white Americans, according to a paper published by Princeton University researchers in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Across eight studies including 1,200 participants, the researchers looked at two different approaches to diversity: an "instrumental rationale," which asserts that including ...

2021-04-12

BOSTON - Many patients with cancer receive immune checkpoint inhibitors that strengthen their immune response against tumor cells. While the medications can be life-saving, they can also cause potentially life-threatening side effects in internal organs. This double-edged sword makes it challenging for clinicians to decide who should be considered candidates for treatment. A new analysis led by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) indicates which patients are at elevated risk of side effects severe enough to require hospitalization. The findings are published in the END ...

2021-04-12

BOSTON - Immune checkpoint inhibitors, which boost the immune system's response against tumor cells, have transformed treatment for many advanced cancers, but short-term clinical trials and small observational studies have linked the medications with various side effects, most commonly involving the skin. A more comprehensive, population-level analysis now provides a thorough look at the extent of these side effects and provides insights on which patients may be more likely to experience them. The research was led by investigators at Massachusetts General ...

2021-04-12

Abstract #LB008

HOUSTON -- A preclinical study led by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center shows an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) targeting surface protein MT1-MMP can act as a guided missile in eradicating osteosarcoma tumor cells without damaging normal tissues. This technology, using precision therapy targeting of cell-surface proteins through a Bicycle toxin conjugate (BTC), shows encouraging results for the treatment of osteosarcoma.

Findings from the study were presented today by Yifei Wang, M.D., a postdoctoral fellow of Pediatrics Research, at the virtual ...

2021-04-12

Blood taken from a small group of children before the COVID-19 pandemic contains memory B cells that bind SARS-CoV-2 and weakly cross-react with other coronaviruses, a new study finds, while adult blood and tissue showed few such cells. "Further study of the role of cross-reactive memory B cell populations... will be important for ongoing improvement of vaccines to SARS-CoV-2, its viral variants, and other pathogens," the authors say. As the COVID-19 pandemic has continued, children have often exhibited faster viral clearance and lower viral antigen loads than adults; whether B cell repertoires against SARS-CoV-2 (and other pathogens) differ between children and ...

2021-04-12

WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- Nitrogen is an element basic for life -- plants need it, animals need it, it's in our DNA -- but when there's too much nitrogen in the environment, things can go haywire. On Cape Cod, excess nitrogen in estuaries and salt marshes can lead to algal blooms, fish kills, and degradation of the environment.

In a study published in Environmental Research Letters, scientists at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) Ecosystems Center examine ways to reduce the nitrogen footprint of smaller institutions, like the MBL, by focusing on a bottom-up approach.

"This bottom-up approach is all about balancing the needs of various stakeholders to come up with the best, ...

2021-04-12

When winter storms threaten to make travel dangerous, people often turn to salt, spreading it liberally over highways, streets and sidewalks to melt snow and ice. Road salt is an important tool for safety, because many thousands of people die or are injured every year due to weather related accidents. But a new study led by Sujay Kaushal of the University of Maryland warns that introducing salt into the environment--whether it's for de-icing roads, fertilizing farmland or other purposes--releases toxic chemical cocktails that create a serious and growing global threat to our freshwater supply and human health.

Previous studies by Kaushal and his team showed that added salts in the environment can interact with soils and infrastructure to release a cocktail of metals, ...

2021-04-12

Researchers have genetically engineered a probiotic yeast to produce beta-carotene in the guts of laboratory mice. The advance demonstrates the utility of work the researchers have done to detail how a suite of genetic engineering tools can be used to modify the yeast.

"There are clear advantages to being able to engineer probiotics so that they produce the desired molecules right where they are needed," says Nathan Crook, corresponding author of the study and an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at North Carolina State University. "You're not just delivering drugs or nutrients; you are effectively manufacturing the drugs or nutrients on site."

The study focused ...

2021-04-12

Spanking may affect a child's brain development in similar ways to more severe forms of violence, according to a new study led by Harvard researchers.

The research, published recently in the journal Child Development, builds on existing studies that show heightened activity in certain regions of the brains of children who experience abuse in response to threat cues.

The group found that children who had been spanked had a greater neural response in multiple regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), including in regions that are part of the salience network. These areas of the brain respond to cues in the environment that tend ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists discover three liquid phases in aerosol particles

Findings could help explain how air pollutants interact with the atmosphere