(Press-News.org) A new study verifies the age and origin of one of the oldest specimens of Homo erectus--a very successful early human who roamed the world for nearly 2 million years. In doing so, the researchers also found two new specimens at the site--likely the earliest pieces of the Homo erectus skeleton yet discovered. Details are published today in the journal Nature Communications.

"Homo erectus is the first hominin that we know about that has a body plan more like our own and seemed to be on its way to being more human-like," said Ashley Hammond, an assistant curator in the American Museum of Natural History's Division of Anthropology and the lead author of the new study. "It had longer lower limbs than upper limbs, a torso shaped more like ours, a larger cranial capacity than earlier hominins, and is associated with a tool industry--it's a faster, smarter hominin than Australopithecus and earliest Homo."

In 1974, scientists at the East Turkana site in Kenya found one of the oldest pieces of evidence for H. erectus: a small skull fragment that dates to 1.9 million years. The East Turkana specimen is only surpassed in age by a 2-million-year-old skull specimen in South Africa. But there was pushback within the field, with some researchers arguing that the East Turkana specimen could have come from a younger fossil deposit and was possibly moved by water or wind to the spot where it was found. To pinpoint the locality, the researchers relied on archival materials and geological surveys.

"It was 100 percent detective work," said Dan Palcu, a geoscientist at the University of São Paulo and Utrecht University who coordinated the geological work. "Imagine the reinvestigation of a 'cold case' in a detective movie. We had to go through hundreds of pages from old reports and published research, reassessing the initial evidence and searching for new clues. We also had to use satellite data and aerial imagery to find out where the fossils were discovered, recreate the 'scene,' and place it in a larger context to find the right clues for determining the age of the fossils."

Although located in a different East Turkana collection area than initially reported, the skull specimen was found in a location that had no evidence of a younger fossil outcrop that may have washed there. This supports the original age given to the fossil.

Within 50 meters of this reconstructed location, the researchers found two new hominin specimens: a partial pelvis and a foot bone. Although the researchers say they could be from the same individual, there's no way to prove that after the fossils have been separated for so long. But they might be the earliest postcrania--"below the head"--specimens yet discovered for H. erectus.

The scientists also collected fossilized teeth from other kinds of vertebrates, mostly mammals, from the area. From the enamel, they collected and analyzed isotope data to paint a better picture of the environment in which the H. erectus individual lived.

"Our new carbon isotope data from fossil enamel tell us that the mammals found in association with the Homo fossils in the area were all grazing on grasses," said Kevin Uno, a paleoecologist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "The enamel oxygen isotope data suggest it was a relatively arid habitat based on comparisons to other enamel data from this area."

The work suggests that this early H. erectus was found in a paleoenvironment that included primarily grazers that prefer open environments to forest areas and was near a stable body of water, as documented by freshwater sponges preserved in the rocks.

Key to the field work driving this study were the students and staff from the Koobi Fora Field School, which provides undergraduate and graduate students with on-the-ground experience in paleoanthropology. The school is run through a collaboration between The George Washington University and the National Museums of Kenya, and with instructors from institutions from around North America, Europe, and Africa. "This kind of renewed collaboration not only sheds new light on verifing the age and origin of Homo erectus but also promotes the National Museums of Kenya's heritage stewardship in research and training," said Emmanuel Ndiema, the head of archaeology at the National Museums of Kenya.

INFORMATION:

Other authors include Silindokuhle S. Mavuso and Zubair Jinnah from the University of the Witwatersrand, Maryse Biernat from Arizona State University and the Institute of Human Origins, David R. Braun from The George Washington University and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Sharon Kuo from Pennsylvania State University, Sahleselasie Melaku from the National Museum of Ethiopia and Addis Ababa University, Sylvia N. Wemanya from the National Museums of Kenya and the University of Nairobi, and David B. Patterson from the University of North Georgia.

Support for this study was provided in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation, grant no.s REU 1852441, 1358178, and 1624398, Fundac?a?o de Amparo a? Pesquisa do Estado de Sa?o Paulo (FAPESP grant no. 2018/208733-6), and the American Museum of Natural History.

Study DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-22208-x

ABOUT THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY (AMNH)

The American Museum of Natural History, founded in 1869 and currently celebrating its 150th anniversary, is one of the world's preeminent scientific, educational, and cultural institutions. The Museum encompasses more than 40 permanent exhibition halls, including those in the Rose Center for Earth and Space, as well as galleries for temporary exhibitions. The Museum's approximately 200 scientists draw on a world-class research collection of more than 34 million artifacts and specimens, some of which are billions of years old, and on one of the largest natural history libraries in the world. Through its Richard Gilder Graduate School, the Museum grants the Ph.D. degree in Comparative Biology and the Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) degree, the only such free-standing, degree-granting programs at any museum in the United States. The Museum's website, digital videos, and apps for mobile devices bring its collections, exhibitions, and educational programs to millions around the world. Visit amnh.org for more information.

ITHACA, N.Y. - The muon is a tiny particle, but it has the giant potential to upend our understanding of the subatomic world and reveal an undiscovered type of fundamental physics.

That possibility is looking more and more likely, according to the initial results of an international collaboration - hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory - that involved key contributions by a Cornell team led by Lawrence Gibbons, professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences.

The collaboration, which brought together 200 scientists from 35 institutions in seven countries, set out to confirm the findings of a 1998 experiment that startled physicists by indicating that muons' magnetic ...

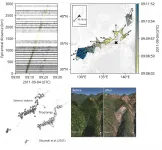

In the Cascadia subduction zone, medium and large-sized "intraslab" earthquakes, which take place at greater than crustal depths within the subducting plate, will likely produce only a few detectable aftershocks, according to a new study.

The findings could have implications for forecasting aftershock seismic hazard in the Pacific Northwest, say Joan Gomberg of the U.S. Geological Survey and Paul Bodin of the University of Washington in Seattle, in their paper published in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Researchers now calculate aftershock forecasts in the region based in part on data from subduction zones around the world. ...

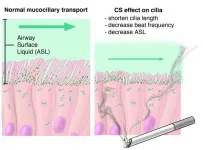

In a series of experiments that began with amoebas -- single-celled organisms that extend podlike appendages to move around -- Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists say they have identified a genetic pathway that could be activated to help sweep out mucus from the lungs of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease a widespread lung ailment.

"Physician-scientists and fundamental biologists worked together to understand a problem at the root of a major human illness, and the problem, as often happens, relates to the core biology of cells," says Doug Robinson, Ph.D., professor of cell ...

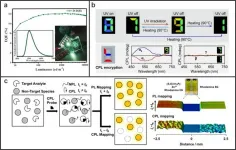

Circularly polarized light exhibits promising applications in future displays and photonic technologies. Traditionally, circularly polarized light is converted from unpolarized light by the linear polarizer and the quarter-wave plate. During this indirectly physical process, at least 50% of energy will be lost. Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) from chiral luminophores provides an ideal approach to directly generate circularly polarized light, in which the energy loss induced by polarized filter can be reduced. Among various chiral luminophores, organic micro-/nano-structures have attracted increasing attention owing to the high quantum efficiency ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Tropical cyclones like typhoons may invoke imagery of violent winds and storm surges flooding coastal areas, but with the heavy rainfall these storms may bring, another major hazard they can cause is landslides--sometimes a whole series of landslides across an affected area over a short time. Detecting these landslides is often difficult during the hazardous weather conditions that trigger them. New methods to rapidly detect and respond to these events can help mitigate their harm, as well as better understand the physical processes themselves.

In a new study published in Geophysical Journal International, a research team led ...

Hokkaido University researchers have clarified different causes of past glacial river floods in the far north of Greenland, and what it means for the region's residents as the climate changes.

The river flowing from the Qaanaaq Glacier in northwest Greenland flooded in 2015 and 2016, washing out the only road connecting the small village of Qaanaaq and its 600 residents to the local airport. What caused the floods was unclear at the time. Now, by combining physical field measurements and meteorological data into a numerical model, researchers at Japan's Hokkaido ...

The semiconductor industry and pretty much all of electronics today are dominated by silicon. In transistors, computer chips, and solar cells, silicon has been a standard component for decades. But all this may change soon, with gallium nitride (GaN) emerging as a powerful, even superior, alternative. While not very heard of, GaN semiconductors have been in the electronics market since 1990s and are often employed in power electronic devices due to their relatively larger bandgap than silicon--an aspect that makes it a better candidate for high-voltage and high-temperature applications. Moreover, current travels quicker through GaN, which ensures fewer switching losses during switching applications.

Not everything about GaN is perfect, however. While impurities are usually desirable ...

People who have recovered from COVID-19, especially those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, may be at risk of developing blood clots due to a lingering and overactive immune response, according to a study led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU) scientists.

The team of researchers, led by NTU Assistant Professor Christine Cheung, investigated the possible link between COVID-19 and an increased risk of blood clot formation, shedding new light on "long-haul COVID" - the name given to the medium- and long-term health consequences of COVID-19.

The findings may help to explain why some people who have recovered from COVID-19 exhibit symptoms of blood clotting complications after their initial recovery. In some cases, they are at increased risk of heart attack, ...

Evolutionary anthropologists from the University of Vienna and colleagues now present evidence for a different explanation, published in PNAS. A larger bony pelvic canal is disadvantageous for the pelvic floor's ability to support the fetus and the inner organs and predisposes to incontinence.

The human pelvis is simultaneously subject to obstetric selection, favoring a more spacious birth canal, and an opposing selective force that favors a smaller pelvic canal. Previous work of scientists from the University of Vienna has already led to a relatively good understanding of this evolutionary "trade-off" and how it results in the high rates of obstructed labor in modern humans. ...

They are diligently stoking thousands of bonfires on the ground close to their crops, but the French winemakers are fighting a losing battle. An above-average warm spell at the end of March has been followed by days of extreme frost, destroying the vines with losses amounting to 90 percent above average. The image of the struggle may well be the most depressingly beautiful illustration of the complexities and unpredictability of global climate warming. It is also an agricultural disaster from Bordeaux to Champagne.

It is the loss of the Arctic sea-ice due to climate warming that has, somewhat paradoxically, been implicated with severe cold and snowy mid-latitude winters.

"Climate change doesn't always manifest in the most ...