INFORMATION:

The study appeared in JHEP Reports.

Other contributors to this work include Barry Zorman, Scott A. Ochsner, Mercedes Barzi, Xavier Legras, Diane Yang, Malgorzata Borowiak, Adam M. Dean, Robert B York, N. Thao N. Galvan, John Goss, William R. Lagor, David D. Moore, David E. Cohen and Pavel Sumazin. The authors are affiliated with one of the following institutions: Baylor College of Medicine, Duke University, Texas Children's Hospital and Weill Cornell Medical College.

This study received support from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL134510 and R01 HL132840), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (R01 DK115461, R01 DK056626, R01 DK103046, R37 DK048872 DK097748) and the American Heart Association (18POST33990445 and 20CDA35340013).

Closer to human -- Mouse model more accurately reproduces fatty liver disease

2021-04-13

(Press-News.org) Human non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a little-understood condition that significantly increases the risk of inflammation, fibrosis and liver cancer and ultimately requires liver transplant.

"NAFLD has been difficult to study mainly because we had no good animal model," said corresponding author Dr. Karl-Dimiter Bissig, who was at Baylor during the development of this project and is now at Duke University.

The disease has both genetic and nutritional components, which have been hard to understand in human studies, and murine models until now had not accurately reflected typical characteristics of human livers with the disease.

Part mouse, part human

"Our goal was to have a mouse model that would allow us to study the disorder and test potential treatments," said co-first author Dr. Beatrice Bissig-Choisat, assistant professor at Duke University. "Applying our lab's yearslong expertise developing chimeric mouse models, those that combine both human and murine cells, we developed mice with livers that were part human and part murine."

The team fed a high-fat diet to the chimeric mice for 12 weeks, then they looked at the livers under the microscope and also studied their metabolic functions and gene expression, comparing them with those of normal mice and of humans with NAFLD.

"We were surprised by the striking differences we observed under the microscope," Bissig said. "In the same liver, the human liver cells were filled with fat, a typical characteristic of the human disease, while the mouse liver cells remained normal."

Next, the researchers analyzed the products of metabolism, in particular the metabolism of fats, of the human liver cells in the mouse model and identified signatures of clinical NAFLD.

"For instance, when mice that received human liver cells fed on a high-fat diet, they started to show features of cholesterol metabolism that looked more like what a patient shows than what other previous animal models showed," said co-first author Dr. Michele Alves-Bezerra, instructor of molecular physiology and biophysics at Baylor. "We made the same observation regarding genes that are regulated after the high-fat diet. All the analyses pointed at cholesterol metabolism being changed in this model in a way that closely replicates what we see in humans."

The researchers also investigated whether the gene expression profiles of the human liver cells in the chimeric model supported the microscopy and metabolic findings.

"We discovered that, compared to the normal mouse liver cells in our model, the fat-laden human liver cells had higher levels of gene transcripts for enzymes involved in cholesterol synthesis," said co-author Dr. Neil McKenna, associate professor of molecular and cellular biology and member of the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center at Baylor. "We wanted to see whether this was also the case in human NAFLD livers."

The team used the web-based platform called the Signaling Pathways Project to create a NAFLD consensome, which surveys previously published clinical studies to identify transcripts whose expression is consistently different between NAFLD livers and healthy ones.

"Using the NAFLD consensome we discovered that, indeed, compared to normal livers, NAFLD livers have consistently higher levels of cholesterol synthesis enzyme transcripts," McKenna said. "This is additional confirmation of the clinical accuracy of our NAFLD model."

Together, the microscopy, metabolic and gene transcription evidence support that the chimeric model closely replicates clinical NAFLD. With this model, researchers have an opportunity to advance the understanding and treatment of this serious condition for which there is no effective therapy.

Not quite human

Another important contribution of this work is that it clearly shows that human and murine cells can be quite different in their responses to factors such as diet, and we have to be careful when interpreting mouse studies of human conditions," Bissig said.

"Here we have a model in which human liver cells respond like in humans. We propose that this model can be used to better understand NAFLD and to identify effective therapies."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study cements age and location of hotly debated skull from early human Homo erectus

2021-04-13

A new study verifies the age and origin of one of the oldest specimens of Homo erectus--a very successful early human who roamed the world for nearly 2 million years. In doing so, the researchers also found two new specimens at the site--likely the earliest pieces of the Homo erectus skeleton yet discovered. Details are published today in the journal Nature Communications.

"Homo erectus is the first hominin that we know about that has a body plan more like our own and seemed to be on its way to being more human-like," said Ashley Hammond, an assistant curator in the American Museum of Natural History's Division of Anthropology and the lead author of the new study. "It had longer lower limbs than upper limbs, a torso ...

Elusive particle may point to undiscovered physics

2021-04-13

ITHACA, N.Y. - The muon is a tiny particle, but it has the giant potential to upend our understanding of the subatomic world and reveal an undiscovered type of fundamental physics.

That possibility is looking more and more likely, according to the initial results of an international collaboration - hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory - that involved key contributions by a Cornell team led by Lawrence Gibbons, professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences.

The collaboration, which brought together 200 scientists from 35 institutions in seven countries, set out to confirm the findings of a 1998 experiment that startled physicists by indicating that muons' magnetic ...

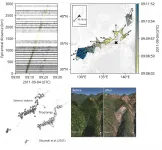

Why are there relatively few aftershocks for certain cascadia earthquakes?

2021-04-13

In the Cascadia subduction zone, medium and large-sized "intraslab" earthquakes, which take place at greater than crustal depths within the subducting plate, will likely produce only a few detectable aftershocks, according to a new study.

The findings could have implications for forecasting aftershock seismic hazard in the Pacific Northwest, say Joan Gomberg of the U.S. Geological Survey and Paul Bodin of the University of Washington in Seattle, in their paper published in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Researchers now calculate aftershock forecasts in the region based in part on data from subduction zones around the world. ...

Amoeba biology reveals potential treatment target for lung disease

2021-04-13

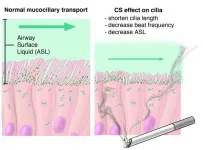

In a series of experiments that began with amoebas -- single-celled organisms that extend podlike appendages to move around -- Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists say they have identified a genetic pathway that could be activated to help sweep out mucus from the lungs of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease a widespread lung ailment.

"Physician-scientists and fundamental biologists worked together to understand a problem at the root of a major human illness, and the problem, as often happens, relates to the core biology of cells," says Doug Robinson, Ph.D., professor of cell ...

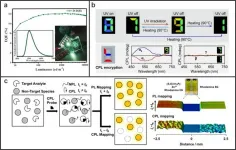

Circularly polarized luminescence from organic micro-/nano-structures

2021-04-13

Circularly polarized light exhibits promising applications in future displays and photonic technologies. Traditionally, circularly polarized light is converted from unpolarized light by the linear polarizer and the quarter-wave plate. During this indirectly physical process, at least 50% of energy will be lost. Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) from chiral luminophores provides an ideal approach to directly generate circularly polarized light, in which the energy loss induced by polarized filter can be reduced. Among various chiral luminophores, organic micro-/nano-structures have attracted increasing attention owing to the high quantum efficiency ...

Tremors triggered by typhoon talas tell tales of tumbling terrain

2021-04-13

Tsukuba, Japan - Tropical cyclones like typhoons may invoke imagery of violent winds and storm surges flooding coastal areas, but with the heavy rainfall these storms may bring, another major hazard they can cause is landslides--sometimes a whole series of landslides across an affected area over a short time. Detecting these landslides is often difficult during the hazardous weather conditions that trigger them. New methods to rapidly detect and respond to these events can help mitigate their harm, as well as better understand the physical processes themselves.

In a new study published in Geophysical Journal International, a research team led ...

Modeling past and future glacial floods in northern Greenland

2021-04-13

Hokkaido University researchers have clarified different causes of past glacial river floods in the far north of Greenland, and what it means for the region's residents as the climate changes.

The river flowing from the Qaanaaq Glacier in northwest Greenland flooded in 2015 and 2016, washing out the only road connecting the small village of Qaanaaq and its 600 residents to the local airport. What caused the floods was unclear at the time. Now, by combining physical field measurements and meteorological data into a numerical model, researchers at Japan's Hokkaido ...

"Shedding light" on the role of undesired impurities in gallium nitride semiconductors

2021-04-13

The semiconductor industry and pretty much all of electronics today are dominated by silicon. In transistors, computer chips, and solar cells, silicon has been a standard component for decades. But all this may change soon, with gallium nitride (GaN) emerging as a powerful, even superior, alternative. While not very heard of, GaN semiconductors have been in the electronics market since 1990s and are often employed in power electronic devices due to their relatively larger bandgap than silicon--an aspect that makes it a better candidate for high-voltage and high-temperature applications. Moreover, current travels quicker through GaN, which ensures fewer switching losses during switching applications.

Not everything about GaN is perfect, however. While impurities are usually desirable ...

NTU Singapore study investigates link between COVID-19 and risk of blood clot formation

2021-04-13

People who have recovered from COVID-19, especially those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, may be at risk of developing blood clots due to a lingering and overactive immune response, according to a study led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU) scientists.

The team of researchers, led by NTU Assistant Professor Christine Cheung, investigated the possible link between COVID-19 and an increased risk of blood clot formation, shedding new light on "long-haul COVID" - the name given to the medium- and long-term health consequences of COVID-19.

The findings may help to explain why some people who have recovered from COVID-19 exhibit symptoms of blood clotting complications after their initial recovery. In some cases, they are at increased risk of heart attack, ...

Childbirth versus pelvic floor stability

2021-04-13

Evolutionary anthropologists from the University of Vienna and colleagues now present evidence for a different explanation, published in PNAS. A larger bony pelvic canal is disadvantageous for the pelvic floor's ability to support the fetus and the inner organs and predisposes to incontinence.

The human pelvis is simultaneously subject to obstetric selection, favoring a more spacious birth canal, and an opposing selective force that favors a smaller pelvic canal. Previous work of scientists from the University of Vienna has already led to a relatively good understanding of this evolutionary "trade-off" and how it results in the high rates of obstructed labor in modern humans. ...