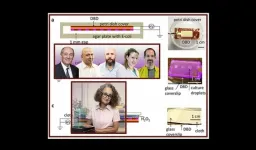

(Press-News.org) The COVID-19 pandemic has cast a harsh light on the urgent need for quick and easy techniques to sanitize and disinfect everyday high-touch objects such as doorknobs, pens, pencils, and personal protective gear worn to keep infections from spreading. Now scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory and the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT) have demonstrated the first flexible, hand-held, device based on low-temperature plasma -- a gas that consists of atoms, molecules, and free-floating electrons and ions -- that consumers can quickly and easily use to disinfect surfaces without special training.

Recent experiments show that the prototype, which operates at room temperature under normal atmospheric pressure, can eliminate 99.99 percent of the bacteria on surfaces, including textiles and metals in just 90 seconds. The device has shown a still-higher 99.9999 percent effectiveness when used with the antiseptic hydrogen peroxide. Scientists think it will be similarly effective against viruses. "We're testing it right now with human viruses," said PPPL physicist Sophia Gershman, first author of a paper in Scientific Reports that describes the device and the research behind it.

Positive results welcomed

The positive results were welcome at PPPL, which is widening its fusion research and plasma science portfolios. "We are very excited to see plasmas used for a broader range of applications that could potentially improve human health," said Jon Menard, deputy director for research at PPPL.

The flexible hand-held device, called a dielectric barrier discharge (DBD), is built like a sandwich, Gershman said. "It's a high-voltage slice of bread on cheese that is an insulator and a grounded piece of bread with holes in it," she said.

The high-voltage slice of "bread" is an electrode made of copper tape. The other slice is a grounded electrode patterned with holes to let the plasma flow through. Between these slices lies the "cheese" of insulating tape. "Basically it's all flexible tape like Scotch tape or duct tape," Gershman said. "The ground electrode faces the users and makes the device safe to use."

The room-temperature plasma interacts with air to produce what are called reactive oxygen and nitrogen species -- molecules and atoms of the two elements -- along with a mixture of electrons, currents, and electrical fields. The electrons and fields team up to enable the reactive species to penetrate and destroy bacteria cell walls and kill the cells.

Room-temperature plasmas, which compare with the fusion plasmas PPPL studies that are many times hotter than the core of the sun, are produced by sending short pulses of high-speed electrons through gases like air, creating the plasma and leaving no time for it to heat up. Such plasmas are also far cooler than the thousand-degree plasmas that the laboratory studies to synthesize nanoparticles and conduct other research.

A special feature of the device is its ability to improve the action of hydrogen peroxide, a common antiseptic cleanser. "We demonstrate faster disinfection than plasma or hydrogen peroxide alone in stable low power operation," the authors write. "Hence, plasma activation of a low concentration hydrogen peroxide solution, using a hand-held flexible DBD device results in a dramatic improvement in disinfection."

Novel collaboration

Achieving these results was a novel collaboration that brought together the plasma physics expertise of PPPL and the biological know-how of a laboratory at NJIT. "While we usually are a neurobiology lab that studies locomotion, we were eager to collaborate with PPPL on a project related to COVID-19," said Gal Haspel, a professor of biological sciences at NJIT and a co-author of the paper.

Performing the plasma disinfection tests was co-author Maria Benem Harreguy, a graduate student in biological sciences at NJIT, with assistance from Gershman. "She did all the experiments and without her we wouldn't have this study," Gershman said.

The idea for this research began "as soon as we got into the COVID lockdown last March," said PPPL physicist and co-author Yevgeny Raitses, who directs the Princeton Collaborative Temperature Plasma Research Facility (PCRF) -- a joint venture of PPPL and Princeton University supported by the DOE Office of Science (FES) that provided resources for this work through a user project. "We at PCRF were thinking of how to help in fighting against COVID through our low-temperature plasma research, and it's been exciting for us to continue this collaboration," he said.

Raitses guided the PPPL side of the project, which included setting up the DBD based on a printed surface design and characterizing the plasma discharge in this device, and oversaw the ongoing collaboration with NJIT. Going forward, he said, "we are working to get access to a facility in which we will be able to apply the DBD and other relevant devices against the SARS CoV-2 virus" that causes COVID-19. "Also under way is research with immunologists and virologists at Princeton University and Rutgers University to expand the applicability of developed plasma devices to a broader range of viruses."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the paper include Shurik Yatom, who introduced the flex DBD idea and conducted physics research, and physicist Phillip Efthimion, who heads the PPPL Plasma Science & Technology Department and oversees the PCRF. Efthmion proposed combining hydrogen peroxide with plasma, which allowed boosting the disinfection properties of the plasma device.

PPPL, on Princeton University's Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, N.J., is devoted to creating new knowledge about the physics of plasmas -- ultra-hot, charged gases -- and to developing practical solutions for the creation of fusion energy. The Laboratory is managed by the University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science, which is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.

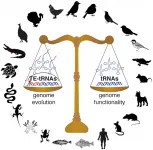

Birds have been shaped by evolution in many ways that have made them distinct from their vertebrate cousins. Over millions of years of evolution, our feathered friends have taken to the skies, accompanied by unique changes to their skeleton, musculature, respiration, and even reproductive systems. Recent genomic analyses have identified another unique aspect of the avian lineage: streamlined genomes. Although bird genomes contain roughly the same number of protein-coding genes as other vertebrates, their genomes are smaller, containing less noncoding DNA. Scientists are still exploring the potential consequences of this genome reduction on bird biology. In a new ...

UPTON, NY--Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) have developed a new mathematical model for predicting how COVID-19 spreads. This model not only accounts for individuals' varying biological susceptibility to infection but also their levels of social activity, which naturally change over time. Using their model, the team showed that a temporary state of collective immunity--what they coined "transient collective immunity"--emerged during early, fast-paced stages of the epidemic. However, subsequent "waves," ...

An alloy is typically a metal that has a few per cent of at least one other element added. Some aluminium alloys have a seemingly strange property.

"We've known that aluminium alloys can become stronger by being stored at room temperature - that's not new information," says Adrian Lervik, a physicist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

The German metallurgist Alfred Wilm discovered this property way back in 1906. But why does it happen? So far the phenomenon has been poorly understood, but now Lervik and his colleagues from NTNU and SINTEF, the largest independent research institute in Scandinavia, have tackled that question.

Lervik recently completed his doctorate at NTNU's Department of Physics. His work explains an important part of this ...

Patients who have preexisting respiratory conditions such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and live in areas with high levels of air pollution have a greater chance of hospitalization if they contract COVID-19, says a University of Cincinnati researcher.

Angelico Mendy, MD, PhD, assistant professor of environmental and public health sciences, at the UC College of Medicine, looked at the health outcomes and backgrounds of 1,128 COVID-19 patients at UC Health, the UC-affiliated health care system in Greater Cincinnati.

Mendy led a team of researchers in an individual-level study which used a statistical model to evaluate the association between long-term exposure to particulate matter less or equal to 2.5 micrometers -- it refers to a mixture of tiny particles and ...

Researchers have found a long-sought enzyme that prevents cancer by enabling the breakdown of proteins that drive cell growth, and that causes cancer when disabled.

Publishing online in Nature on April 14, the new study revolves around the ability of each human cell to divide in two, with this process repeating itself until a single cell (the fertilized egg) becomes a body with trillions of cells. For each division, a cell must follow certain steps, most of which are promoted by proteins called cyclins.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the work revealed that an enzyme called AMBRA1 labels a key class of cyclins for destruction by cellular machines that break down proteins. The work finds that the enzyme's control of cyclins is essential ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Eurasian Blackcaps are spunky and widespread warblers that breed across much of Europe. Many of them migrate south to the Mediterranean region and Africa after the breeding season. But thanks to a changing climate and an abundance of food resources offered by people across the United Kingdom and Ireland, some populations of Blackcaps have recently been heading north for the winter, spending the colder months in backyard gardens of the British Isles.

New research published this week in Global Change Biology shows some of the ways that bird feeders, fruit-bearing plants, and a warming world are changing both the movements and the physiology of the Blackcaps that spend the winter in Great Britain and Ireland.

"Many migratory birds are ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Most young women already know that tanning is dangerous and sunbathe anyway, so a campaign informing them of the risk should take into account their potential resistance to the message, according to a new study.

Word choice and targeting a specific audience are part of messaging strategy, but there is also psychology at play, researchers say - especially when the message is telling people something they don't really want to hear.

"A lot of thought goes into the content, but possibly less thought goes into the style," said Hillary Shulman, senior author of the study and an assistant ...

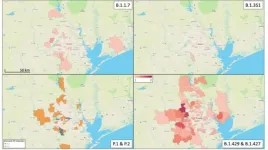

Philadelphia, April 14, 2021 - In late 2020, several concerning SARS-CoV-2 variants emerged globally. They are believed to be more easily transmissible, and there is concern that some may reduce the effectiveness of antibody treatments and vaccines. An extensive genome sequencing program run by the Houston Methodist health system has identified all six of the currently identified SARS-CoV-2 variants in their patients. A new study appearing in The American Journal of Pathology, published by Elsevier, finds that the variants are widely spread across the Houston metropolitan area.

"Before the SARS-CoV-2 virus arrived in Houston, we planned an integrated strategy to confront ...

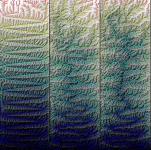

A new study by former University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign graduate student Jeffrey Kwang, now at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Abigail Langston, of Kansas State University; and Illinois civil and environmental engineering professor Gary Parker takes a closer look at the vertical and lateral – or depth and width – components of river erosion and drainage patterns. The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“A tree’s dendritic structure exists to provide fresh ends for leaves to grow and collect as much light as possible,” Parker said. “If you chop off some branches, they will regrow in a dendritic pattern. ...

LA JOLLA, CALIF. - April 14, 2021 - Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute have shown that two existing drug candidates--JAK inhibitors and Mepron--hold potential as treatments for a deadly acute myeloid leukemia (AML) subtype that is more common in children. The foundational study, published in the journal Blood, is a first step toward finding effective treatments for the hard-to-treat blood cancer.

"While highly successful therapies have been found for other blood cancers, most children diagnosed with this AML subtype are still treated with harsh, toxic chemotherapies," says Ani Deshpande, Ph.D., assistant professor in Sanford Burnham Prebys' ...