CHOP-led research study identifies key target in treatment-resistant hemophilia A

Study implicates BAFF in the 30% of patients who do not respond to coagulation protein therapy, a finding that could lead to better treatments and outcomes

2021-04-15

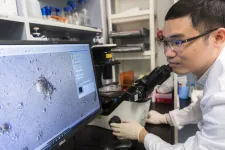

(Press-News.org) Philadelphia, April 15, 2021--Researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have identified a key target that may be responsible for treatment failure in about 30% of patients with hemophilia A. The target, known as B cell activating factor (BAFF), appears to promote antibodies against and inhibitors of the missing blood clotting factor that is given to these patients to control their bleeding episodes. The findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, raise the possibility of using anti-BAFF therapies, potentially in combination with immune tolerance therapies, to tame the immune response in some patients with severe hemophilia A.

Hemophilia A is the most common inherited bleeding disorder, affecting 1 in 10,000 men worldwide. The condition is the result of a missing coagulation factor known as factor VIII (FVIII), which leads to uncontrolled bleeding episodes, joint disease, and increased risk of death. To control the disease, patients receive infusions of the FVIII protein to replace the missing coagulation factor, but for reasons scientists haven't fully understood, approximately 30% of patients with severe hemophilia A develop neutralizing antibodies known as FVIII inhibitors that prevent the treatment from working, which negatively affects disease management.

Some patients resistant to FVIII protein replacement therapy receive immune tolerance induction (ITI), wherein high doses of FVIII are given over a period of one to two years to build up tolerance. However, ITI is demanding on patients and families, and the treatment - which is both costly and invasive - isn't always effective.

To both uncover the mechanism behind the anti-FVIII immune response and expose a potential target, the researchers explored the possible role of BAFF in regulating FVIII inhibitors. Prior studies have shown that high plasma BAFF levels are implicated in some autoimmune diseases, as well as antibody-mediated transplant rejections. Using both adult and pediatric hemophilia A patient samples and hemophilia A mouse models, the researchers explored their hypothesis that BAFF may play a role in the generation and maintenance of FVIII antibodies.

The research team, led by CHOP and Indiana University School of Medicine, found that BAFF levels were elevated in pediatric and adult patients who were resistant to FVIII replacement therapy; after successful ITI, those BAFF levels decreased to levels similar to non-inhibitor patients. In patients for whom ITI was unsuccessful, BAFF levels remained elevated. Working in mouse models, the researchers found that giving the mice prophylactic anti-BAFF therapy before FVIII treatment prevented inhibitors. In mice with established inhibitors, the researchers found that treating the mice with both anti-BAFF and rituximab, a chimeric antibody that depletes mature B cells, dramatically reduced FVIII inhibitor titers by, at least in part, reducing FVIII-specific plasma cells.

"Our data suggest that BAFF may regulate the generation and maintenance of FVIII inhibitors, as well as anti-FVIII B cells," said co-senior author Valder R. Arruda, MD, PhD, a researcher in the Division of Hematology at CHOP and director of CHOP's NIH-funded Center for the Investigation of Factor VIII Immunogenicity. "Given that an FDA-approved anti-BAFF antibody is currently used to suppress the immune response in autoimmune diseases, future research should explore the use of this treatment in combination with rituximab to achieve better outcomes for hemophilia A patients resistant to FVIII protein replacement therapy."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Dr. Bhavya Doshi, MD from the Division of Hematology at CHOP and collaborators from Indiana University School of Medicine, the research included contributions by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, the Center for Bleeding Disorders and Coagulation at Careggi University Hospital, the Aflac Cancer Center and Blood Disorders Center at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory School of Medicine, and Tulane University School of Medicine.

Doshi BS et al. "B cell activating factor modulates the factor VIII immune response in hemophilia A," Journal of Clinical Investigation, April 15, 2021, DOI: 10.1172/JCI142906

<

About Children's Hospital of Philadelphia: Children's Hospital of Philadelphia was founded in 1855 as the nation's first pediatric hospital. Through its long-standing commitment to providing exceptional patient care, training new generations of pediatric healthcare professionals, and pioneering major research initiatives, Children's Hospital has fostered many discoveries that have benefited children worldwide. Its pediatric research program is among the largest in the country. In addition, its unique family-centered care and public service programs have brought the 595-bed hospital recognition as a leading advocate for children and adolescents. For more information, visit http://www.chop.edu

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-15

Philadelphia, April 15, 2021 - Early and accurate diagnosis leads to optimal recovery from concussion. Over the past year across a series of studies, the Minds Matter Concussion Program research team at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) has systematically evaluated the use of the visio-vestibular examination (VVE) and its ability to enhance concussion diagnosis and management. The latest of these studies published online today in the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine.

The VVE involves a series of brief eye movement and balance tests intended to identify deficits in brain function involving the visual and vestibular systems. Researchers found that the VVE presents several advantages over current clinical measures, moving beyond subjective symptoms ...

2021-04-15

April 15, 2021 - Decades after their days on the gridiron, middle-aged men who played football in high school are not experiencing greater problems with concentration, memory, or depression compared to men who did not play football, reports a study in Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"Men who played high-school football did not report worse brain health compared with those who played other contact sports, noncontact sports, or did not participate in sports during high school," according to the new research, led by Grant L. Iverson, PhD, of Harvard Medical School. The study offers reassurance that playing high-school football is not, in itself, a risk factor for cognitive or mood ...

2021-04-15

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive type of breast cancer with a high fatality rate. Currently, chemotherapy is the major treatment option, but the clinical result is unsatisfactory. A research team led by biologists at City University of Hong Kong (CityU) has identified and characterised a set of specific super-enhancers that stimulate the activity of the related critical cancer genes. The research has also discovered that the deletion of certain specific super-enhancers can reduce tumour cell growth. The latest findings may help discover new effective drug targets for TNBC patients to improve their survival chance.

Traditionally, cancer research ...

2021-04-15

A key portion of MIT's campus overlaps with Kendall Square, the bustling area in East Cambridge where students, residents, and tech employees scurry around in between classes, meetings, and meals. Where are they all going? Is there a way to make sense of this daily flurry of foot traffic?

In fact, there is: MIT Associate Professor Andres Sevtsuk has made Kendall Square the basis of a newly published model of pedestrian movement that could help planners and developers better grasp the flow of foot traffic in all cities.

Sevtsuk's work emphasizes the functionality of a neighborhood's elements, above and beyond its physical form, making the model one that could be ...

2021-04-15

A new scientific discovery in Australia by Flinders University has recorded for the first time how ghost currents and sediments can 'undo' the force of gravity.

The new theory, just published in the Journal of Marine Systems, helps explain obscure events in which suspended sediment particles mysteriously move upward, not downward, on the slope of submarine canyons of the deep sea.

While this activity seems to contradict the laws of gravity, Flinders University physical oceanographer Associate Professor Jochen Kaempf has found an answer, devising the first scientific explanation of the observed upslope sediment transport.

"To put it simply, the vehicle of this transport are currents that, while carrying ...

2021-04-15

Many long for a return to a post-pandemic "normal," which, for some, may entail concerts, travel, and large gatherings. But how to keep safe amid these potential public health risks?

One possibility, according to a new study, is dogs. A proof-of-concept investigation published today in the journal PLOS ONE suggests that specially trained detection dogs can sniff out COVID-19-positive samples with 96% accuracy.

"This is not a simple thing we're asking the dogs to do," says Cynthia Otto, senior author on the work and director of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine Working Dog Center. "Dogs have to ...

2021-04-15

Do freshwater snails make good tennis players? One of them certainly has the name for it.

Enter Travunijana djokovici, a new species of aquatic snail named after famous Serbian tennis player Novak Djokovic.

Slovak biospeleologist Jozef Grego and Montenegrin zoologist Vladimir Pesic of the University of Montenegro discovered the new snail in a karstic spring near Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro, during a field trip in April 2019. Their scientific article, published in the open-access, peer-reviewed journal Subterranean Biology, says they named it after Djokovic "to acknowledge his inspiring enthusiasm and energy."

"To discover some of the world's rarest animals that inhabit the unique underground habitats of the Dinaric karst, to reach inaccessible cave and spring habitats ...

2021-04-15

WASHINGTON (April 15, 2021) -- Clusters of a virus known to cause stomach flu are resistant to detergent and ultraviolet disinfection, according to new research co-led by END ...

2021-04-15

Since the 1970s, the Standard Model of Physics has served as the basis from which particle physics are investigated. Both experimentalists and theoretical physicists have tested the Standard Model's accuracy, and it has remained the law of the land when it comes to understanding how the subatomic world behaves.

This week, cracks formed in that foundational set of assumptions. Researchers of the "Muon g-2" collaboration from the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (FNAL) in the United States published further experimental findings that show that muons--heavy subatomic relatives of electrons--may have a larger "magnetic moment" than earlier Standard Model estimates had predicted, indicating that an unknown particle or force might be influencing ...

2021-04-15

The DNA molecule is not naked in the nucleus. Instead, it is folded in a very organized way by the help of different proteins to establish a unique spatial organization of the genetic information. This 3D spatial genome organization is fundamental for the regulation of our genes and has to be established de novo by each individual during early embryogenesis. Researchers at the MPI of Immunobiology and Epigenetics in Freiburg in collaboration with colleagues from the Friedrich Mischer Institute in Basel now reveal a yet unknown and critical role of the protein HP1a in the 3D genome re-organization after fertilisation. The study published in the scientific journal Nature identifies HP1a as an epigenetic regulator that is involved in establishing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] CHOP-led research study identifies key target in treatment-resistant hemophilia A

Study implicates BAFF in the 30% of patients who do not respond to coagulation protein therapy, a finding that could lead to better treatments and outcomes