Understanding how DNA repairs itself may lead to better cancer treatment

High resolution electron microscopy imaging shows how damage-sensing proteins recognize DNA breaks and then bridge them together

2021-04-15

(Press-News.org) From cancer treatment to sunlight, radiation and toxins can severely damage DNA in both harmful and healthy cells. While the body has evolved to efficiently treat and restore damaged cells, the mechanisms that allow this natural repair remain misunderstood.

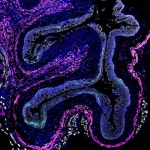

In a new study, Northwestern University researchers have used cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize this process by illuminating the mysterious cycle of DNA breakage sensing and repair. The researchers believe this new information could potentially form the basis for understanding how cells respond to chemotherapy and radiation and potentially even lead to improved cancer treatments.

Published Wednesday, April 14 in the journal Nature, the research offers new insight into how proteins work in concert to identify and resolve DNA double-strand breaks (DSB).

When a double strand break, or DSB -- the most severe form of DNA damage -- occurs, the repair pathway may insert or delete genes at the break site or potentially rearrange genes throughout the strand. In cases where chromosomal rearrangement occurs, catastrophic changes can lead to the development of cancer.

Using cryo-EM, researchers can obtain 3D images of macromolecular structures at atomic resolution. According to Yuan He, an assistant of molecular bioscience in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, cryo-EM's ability to image dynamic machinery "goes way beyond the capabilities" of other structural biology techniques.

Imaging DNA-protein complexes at various transitory phases allowed He's team to identify and create a model of a cell's repair pathway.

"There are many factors that work in concert to seal the nick," said He, the study's corresponding author. "We're taking the most straightforward way to solve the problem -- by looking at proteins as they identify and repair a break."

The resulting model shows that, at times, two copies of DSB recognition complexes can hold together and bridge DSBs as the complexes signal for other factors to come to the breaking site. In another essential state, proteins align the two strands of DNA for a ligase to come and seal the nick. The lab then proposed a model of this pathway, showing how DNA bridges and aligns as it transfers between states.

[VIDEO] As the bottom component of the DNA-protein structure comes under stress, DNA strands are bridged to close proximity; once the component returns to a more relaxed state, the movement then joins the two DNA strands together.

"Seeing is believing" is a common saying in molecular biology, and one He thinks applies to his research directly. By observing the elegant process directly, an observer can easily make connections and understand how the complex system works together. But before this technology was available, He said it was akin to a blind person identifying an elephant by touch.

"Breakthroughs are usually thought of for something big and complex," said Siyu Chen, a postdoctoral student in He's lab and first author on the paper. "The question we're answering is fundamental and straightforward: DNA has been broken apart -- so how do proteins join them together?"

The lab hopes findings have implications for how our cells come back from and respond to radiation and chemotherapy. Future research could bring more targeted therapies for this newly understood pathway.

INFORMATION:

Work in the He lab is supported by a Cornew Innovation Award from the Chemistry of Life Processes Institute at Northwestern University, an Institutional Research Grant from the American Cancer Society (award number IRG-15-173-21), and an H Foundation Core Facility Pilot Project Award (award number U54CA193419). The research was also supported by the National Institute of Health (award number R01GM135651, T32GM008382, and P01CA092584).

The paper is titled "Structural basis of long-range to short-range synaptic transition in NHEJ."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-15

The complex patterns of genetic ancestry uncovered from genomic data in health care systems can provide valuable insights into both genetic and environmental factors underlying many common and rare diseases--insights that are far more targeted and specific than those derived from traditional ethnic or racial labels like Hispanic or Black, according to a team of Mount Sinai researchers.

In a study in the journal Cell, the team reported that this information could be used to better understand and predict which populations are more susceptible to certain disorders--including cancers, asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease--and to potentially develop early interventions.

"This is the first time researchers have shown how ...

2021-04-15

Engaging in household chores may be beneficial for brain health in older adults. In a recent Baycrest study, older adults who spent more time on household chores showed greater brain size, which is a strong predictor of cognitive health.

"Scientists already know that exercise has a positive impact on the brain, but our study is the first to show that the same may be true for household chores," says Noah Koblinsky, lead author of the study, Exercise Physiologist and Project Coordinator at Baycrest's Rotman Research Institute (RRI). "Understanding how different forms ...

2021-04-15

LOS ANGELES (April 15, 2021) -- Researchers have discovered a new way to transform the tissues surrounding prostate tumors to help the body's immune cells fight the cancer. The discovery, made in human and mouse cells and in laboratory mice, could lead to improvements in immunotherapy treatments for prostate cancer, the second most common cancer in men in the US.

Using a technique called epigenetic reprogramming, investigators altered the tumor and tumor microenvironment by inhibiting expression of a protein known as enhancer of zeste homolog2, or EZH2, which is found at high levels in prostate cancer. This protein ...

2021-04-15

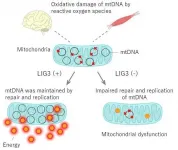

DNA ligase proteins, which facilitate the formation of bonds between separate strands of DNA, play critical roles in the replication and maintenance of DNA. The human genome encodes three different DNA ligase proteins, but only one of those proteins--DNA ligase III (LIG3)--is expressed in mitochondria. LIG3 is therefore crucial for mitochondrial health, and inactivation of the homologous protein in mice causes profound mitochondrial dysfunction and early embryonic mortality. In an article recently published in the peer-reviewed journal Brain, a team of European and Japanese scientists, led by Dr. Mariko Taniguchi-Ikeda from Fujita Health University Hospital, describes a set of seven patients with a novel ...

2021-04-15

Infection with parasitic intestinal worms (helminths) can apparently cause sexually transmitted viral in-fections to be much more severe elsewhere in the body. This is shown by a study led by the Universities of Cape Town and Bonn. According to the study, helminth-infected mice developed significantly more severe symptoms after infection with a genital herpes viruses (Herpes Simplex Virus). The researchers suspect that these results can also be transferred to humans. The results have now appeared in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

In sub-Saharan Africa, both worm infections and sexually transmitted viral diseases are extremely com-mon. These viral infections are also often particularly severe. It is possible that these findings ...

2021-04-15

LIBREVILLE, Gabon (April 15 2021) - A team of scientists led by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and working closely with experts from the Agence Nationale des Parcs Nationaux du Gabon (ANPN) compared methodologies to count African forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis), which were recently acknowledged by IUCN as a separate, Critically Endangered species from African savannah elephants. The study is part of a larger initiative in partnership with Vulcan Inc. to provide the first nationwide census in Gabon for more than 30 years. The results of the census are expected later this ...

2021-04-15

Fifty-five years ago, America's death toll from automobile crashes was sky-high. Nearly 50,000 people died every year from motor vehicle crashes, at a time when the nation's population was much smaller than today.

But with help from data generated by legions of researchers, the country's policymakers and industry made changes that brought the number killed and injured down dramatically.

Research led to changes in everything from road construction and driver's license rules, to hospital trauma care, to laws and social norms about wearing seatbelts and driving while drunk or using a cell phone.

Now, researchers at the University ...

2021-04-15

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have transformed cancer care to the point where the popular Cox proportional-hazards model provides misleading estimates of the treatment effect, according to a new study published April 15 in JAMA Oncology.

The study, "Development and Evaluation of a Method to Correct Misinterpretation of Clinical Trial Results With Long-term Survival," suggests that some of the published survival data for these immunotherapies should be re-analyzed for potential misinterpretation.

The study's senior author, Yu Shyr, PhD, the Harold L. Moses Chair ...

2021-04-15

Scientists at the University of Southampton have conducted a study that highlights the importance of studying a full range of organisms when measuring the impact of environmental change - from tiny bacteria, to mighty whales.

Researchers at the University's School of Ocean and Earth Science, working with colleagues at the universities of Bangor, Sydney and Johannesburg and the UK's National Oceanography Centre, undertook a survey of marine animals, protists (single cellular organisms) and bacteria along the coastline of South Africa.

Lead researcher and postgraduate student ...

2021-04-15

The dynamics of the neural activity of a mouse brain behave in a peculiar, unexpected way that can be theoretically modeled without any fine tuning, suggests a new paper by physicists at Emory University. Physical Review Letters published the research, which adds to the evidence that theoretical physics frameworks may aid in the understanding of large-scale brain activity.

"Our theoretical model agrees with previous experimental work on the brains of mice to a few percent accuracy -- a degree which is highly unusual for living systems," says Ilya Nemenman, Emory professor of physics and biology and senior author of the paper.

The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Understanding how DNA repairs itself may lead to better cancer treatment

High resolution electron microscopy imaging shows how damage-sensing proteins recognize DNA breaks and then bridge them together