(Press-News.org) Almost 80% of South Africans speak one of the SEB family languages as their first language. Their origins can be traced to farmers of West-Central Africa whose descendants over the past two millennia spread south of the equator and finally into Southern Africa.

Since then, varying degrees of sedentism [the practice of living in one place for a long time], population movements and interaction with Khoe and San communities, as well as people speaking other SEB languages, ultimately generated what are today distinct Southern African languages such as isiZulu, isiXhosa and Sesotho.

Despite these linguistic differences, these groups are treated mostly as a single group in genetic studies.

Understanding genetic diversity in a population is critical to the success of disease genetic studies. If two genetically distinct populations are treated as one, the methods normally used to find disease genes could become error prone.

Consideration of these genetic differences is critical to providing a reliable understanding of the genetics of complex diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, in South Africans.

Dr Dhriti Sengupta and Dr Ananyo Choudhury in the Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience (SBIMB) at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, were joint lead authors of the paper published in Nature Communications on 7 April 2021.

The study comprised a multidisciplinary team of geneticists, bioinformaticians, linguists, historians and archaeologists from Wits University (Michèle Ramsay, Scott Hazelhurst, Shaun Aron and Gavin Whitelaw), the University of Limpopo, and partners in Belgium, Sweden and Switzerland.

"South Eastern Bantu-speakers have a clear linguistic division - they speak more than nine distinct languages - and their geography is clear: some of the groups are found more frequently in the north, some in central, and some in southern Africa. Yet despite these characteristics, the SEB groups have so far been treated as a single genetic entity," says Choudhury.

The study found that SEB speaking groups are too different to be treated as a single genetic unit.

"So if you are treating say, Tsonga and Xhosa, as the same population - as was often done until now - you might get a completely wrong gene implicated for a disease," says Sengupta.

ABOUT THE STUDY

The study, titled: "Genetic substructure and complex demographic history of South African Bantu speakers" aimed to find out whether the SEB speakers are indeed a single genetic entity or if they have enough genetic differences to be grouped into smaller units.

Genetic data from more than 5000 participants speaking eight different southern African languages were generated and analysed.

These languages are isiZulu, isiXhosa, siSwati, Xitsonga, Tshivenda, Sepedi, Sesotho and Setswana.

Participants were recruited from research sites in Soweto in Gauteng, Agincourt in Mpumalanga, and Dikgale in Limpopo province.

Genetic differences reflect geography, language and history

The study detected major variations in genetic contribution from the Khoe and San into SEB speaking groups; some groups have received a lot of genetic influx from Khoe and San people, while others have had a very little genetic exchange with these groups.

This variation ranged on average from about 2% in Tsonga to more than 20% in Xhosa and Tswana.

This suggests that SEB speaking groups are too different to be treated as a single genetic unit.

"The study showed that there could be substantial errors in disease gene discovery and disease risk estimation if the differences between South-Eastern-Bantu speaking groups are not taken into consideration," says Sengupta.

The genetic data also show major differences in the history of these groups over the last 1000 years. Genetic exchanges were found to have occurred at different points in time, suggesting a unique journey of each group across the southern African landscape over the past millennium.

These genetic differences are strong enough to impact the outcomes of biomedical genetic research.

Sengupta emphasises, however, that ethnolinguistic identities are complex and cautioned against extrapolating broad conclusions from the findings regarding genetic differences.

"Although genetic data showed differences [separation] between groups, there was also a substantial amount of overlap [similarity]. So while findings regarding differences could have huge value from a research perspective, they should not be generalised," she says.

A GENETIC BLUEPRINT FOR FUTURE HEALTH

A common approach to identify if a genetic variant causes or predisposes us to a disease is to take a set of individuals with a disease (e.g., high blood pressure or diabetes) and another set of healthy individuals without the disease, and then compare the occurrence of many genetic variants in the two sets.

If a variant shows a notable frequency difference between the two sets it is assumed that the genetic variant could be associated with the disease.

"However, this approach depends entirely on the underlying assumption that the two groups consist of genetically similar individuals. One of the major highlights of our study is the observation that Bantu-speakers from two geographic regions - or two ethnolinguistic groups - cannot be treated as if they are the same when it comes to disease genetic studies," says Choudhury.

Future studies, especially those testing a small number of variants, need to be more nuanced and have balanced ethnolinguistic and geographic representation, he says.

This study is the second landmark study in African population genetics, published in the last six months, led by researchers in the Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Wits University.

Professor Michèle Ramsay, director of the SBIMB and corresponding author of the study, says: "The in-depth analysis of several large African genetic datasets has just begun. We look forward to mining these datasets to provide new insights into key population histories and the genetics of complex diseases in Africa".

INFORMATION:

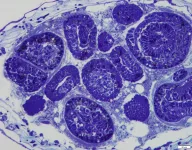

The Cyclostomata is an ancient group of aquatic colonial suspension-feeders from the phylum Bryozoa. The fact that they have unique placentae has been discovered by researchers at St Petersburg University and the University of Vienna. The coenocytes, i.e. large multinucleate cell structures, originate via nuclear multiplication and cytoplasmic growth among the cells surrounding the early embryo. Interestingly, the coenocytes are commonly found among fungi and plants, yet are quite rare in animals. It is the first time coenocytes have been discovered in placenta.

Biologists are well aware that the cells of the living organisms are incredibly different in the way that they behave. They may happen to form a ...

Targeted therapy in early stages of breast cancer can pave the way for a notable higher success rate, shows a study from the University of Bergen, Norway (UiB).

PARP (Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase) inhibitors represent an established targeted therapy for multiple cancer types, including cancers of the prostate, ovary and rare cases of breast cancer.

PARP inhibitors take advantage of defects in a central mechanism of DNA damage repair, observed in these cancers. While such compounds have been successfully applied in ovarian and prostate cancers, to this end only a small minority of patients with breast ...

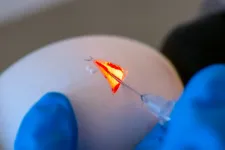

Researchers at the TUM have demonstrated a way to efficiently study molecular mechanisms of disease resistance or biomedical issues in farm animals. Researchers are now able to introduce specific gene mutations into a desired organ or even correct existing genes without creating new animal models for each target gene. This reduces the number of animals required for research..

CRISPR/Cas9 enables desired gene manipulations

CRISPR/Cas9 is a tool to rewrite DNA information. Genes can be inactivated or specifically modified using this method. The CRISPR/Cas9 system consists of two components.

The gRNA (guide RNA) is a short sequence that binds specifically to the ...

Although the problem of gender discrimination is already found in the music industry, music recommendation algorithms would be increasing the gender gap. Andrés Ferraro and Xavier Serra, researchers of the Music Technology research group (MTG) of the UPF Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC), with Christine Bauer, of the University of Utrecht (Netherlands), have recently published a paper on gender balance in music recommendation systems in which they ask themselves how the system should work to avoid gender bias.

At the outset, the authors identified that gender justice was one of the artists' main concerns

Initially, the work by Ferraro, Serra and Bauer ...

MINNEAPOLIS/ST.PAUL (04/20/2021) -- University of Minnesota Medical School researchers have offered new ways to think about the immune system thanks to a recent study published in END ...

PHILADELPHIA - Renter protection policies that have curbed mass evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic have played a key role in preventing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in U.S. cities, according to a new study published in Nature Communications.

Using an epidemiological model to predict how evictions and eviction moratoria would impact the epidemic, the researchers found, for instance, that in a city of 1 million in which 1 percent of households experience eviction monthly, this could lead to up to 49,000 excess COVID-19 infections. In Philadelphia alone, a fivefold increase in ...

An overgrowth of yeast in the gut within the first few months of life may cause changes to the immune system that increase the risk of asthma later on, shows a study published today in eLife.

Asthma is a common and sometimes difficult-to-manage, life-long lung condition that affects one in 10 children in developed countries. The findings explain a possible cause of asthma and may help scientists develop new strategies to prevent or treat the condition.

The period just after birth is a critical window for the development of a healthy immune system and gut microbiome. ...

Charcot Marie Tooth and Dejerine-Sottas syndrome are groups of diseases that involve the breakdown of the myelin sheath covering nerve axons.

As this myelin sheath breaks down, people who have these disorders suffer nerve damage in the arms and legs--those with Dejerine-Sottas disease may never walk or may lose the ability to walk by the time they are teenagers.

Researchers have known that a protein called PMP22, which is important for nerve myelin, is likely involved in the disease. But because the protein is so small and part of the cell membrane, ...

Scientists have produced a comprehensive roadmap of muscle aging in mice that could be used to find treatments that prevent decline in muscle mobility and function, according to a report published today in eLife.

The study reveals which molecules in the muscle are most significantly altered at different life stages, and shows that a molecule called Klotho, when administered to mice in old, but not very old, age, was able to improve muscle strength.

Age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function - called sarcopenia - is associated with loss of mobility and increased risk of falls. Yet, although scientists know how sarcopenia affects the appearance and behaviour of muscle tissues, the underlying molecular mechanisms for sarcopenia remain poorly understood. Current treatments ...

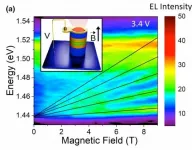

Diodes are widely used electronic devices that act as one-way switches for current. A well-known example is the LED (light-emitting diode), but there is a special class of diodes designed to make use of the phenomenon known as “quantum tunneling”. Called resonant-tunneling diodes (RTDs), they are among the fastest semiconductor devices and are used in countless practical applications, such as high-frequency oscillators in the terahertz band, wave emitters, wave detectors, and logic gates, to take only a few examples. RTDs are also sensitive to light and can be used as photodetectors or optically active elements in optoelectronic circuits.

Quantum tunneling (or the tunnel ...