Recolonization of Europe after the last ice age started earlier than previously thought

2021-04-21

(Press-News.org) A study that appeared today on Current Biology sheds new light on the continental migrations which shaped the genetic background of all present Europeans. The research generates new ancient DNA evidence and direct dating from a fragmentary fossil mandible belonging to an individual who lived ~17,000 years ago in northeastern Italy (Riparo Tagliente, Verona). The results backdate by about 3,000 years the diffusion in Southern Europe of a genetic component linked to Eastern Europe/Western Asia previously believed to have spread westwards during later major warming shifts.

"By looking into the past of this particular individual, who was one of the first settlers of the southern Alps after the Last Glacial peak, we found evidence that the previously documented genetic replacement which changed the makeup of Southern European Hunter Gatherers started at least 17,000 years ago," said lead author Eugenio Bortolini (University of Bologna), "much earlier than we previously thought, and in a very different scenario".

The ancient genome obtained at Riparo Tagliente is in fact of particular importance, "since it supports the persistence of exchange networks and the movement of people across southern Europe immediately after the Last Glacial Maximum, well before the onset of much warmer climatic shifts," said Luca Pagani (University of Padova and Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu), co-first author of the work.

This individual, whose half-mandible had been found at Riparo Tagliente in 1963, shares genetic affinities with an Iberian individual who lived up to 19,000 years ago, and maternal and paternal genetic affinities with southern Italian and European individuals who lived around 14,000 years ago, suggesting that population movements may have spread these genetic variants in Southern Europe even before the occupation of Riparo Tagliente, and may have been intermittent but persisting during colder phases. "Direct dating of human fossils is once again critical to disentangle and interpret complex archaeological contexts", adds Sahra Talamo, coauthor of the study.

The analysis of the mandible also allowed the authors to unveil some details concerning this particular settler of Riparo Tagliente: "The fragment belongs to a young male affected by cementoma, a quite rare anomaly in the development of dental tissue" adds Gregorio Oxilia, co-first author of the study, "and might shed light on the distribution of such conditions in pre-Neolithic societies".

The research was coordinated by the University of Bologna (Italy) in close collaboration with a vast international network including the University of Padova (Italy), the Institute of Genomics of the University of Tartu (Estonia), the University of Tu?bingen (Germany), the University of Ferrara (Italy), the Institute of Genetics and Biophysics of the National Research Council of Italy, KU Leuven (Belgium), Institució Milà i Fontanals of the Spanish National Research Council, Sequentia Biotech (Spain), University of Venice Ca' Foscari (Italy), The "Abdus Salam" International Centre for Theoretical Physics (Trieste, Italy), Monash University (Melbourne , Australia), University of Florence (Italy), and several professional dentist surgeons. Excavations at Riparo Tagliente which made this study possible are led and supervised by Federica Fontana and coordinated by the University of Ferrara.

"This finding opens important questions concerning the role and impact of population movements on the major cultural transitions documented by archaeologists in Southern Europe" concludes Stefano Benazzi, senior author of the study, "some of which temporally coincide with the date emerged for the individual found at Riparo Tagliente. Future research will dig more into these new hypotheses concerning the ancestry of modern Europeans".

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-21

Astronomers using data from NASA and the ESA (European Space Agency) telescopes have released a new all-sky map of the outermost region of our galaxy. Known as the galactic halo, this area lies outside the swirling spiral arms that form the Milky Way's recognizable central disk and is sparsely populated with stars. Though the halo may appear mostly empty, it is also predicted to contain a massive reservoir of dark matter, a mysterious and invisible substance thought to make up the bulk of all the mass in the universe.

The data for the new map comes from ESA's Gaia mission and NASA's Near Earth Object Wide Field Infrared Survey Explorer, or NEOWISE, which operated from 2009 to 2013 under the moniker WISE. The study, led by astronomers at the Center for ...

2021-04-21

Substantial cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions could be achieved by raising water levels in agricultural peatlands, according to a new study in the journal Nature.

Peatlands occupy just three per cent of the world's land surface area but store a similar amount of carbon to all terrestrial vegetation, as well as supporting unique biodiversity.

In their natural state, they can mitigate climate change by continuously removing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it securely under waterlogged conditions for thousands of years.

But many peatland areas have been substantially modified by human activity, including drainage for agriculture and forest plantations. This results in the ...

2021-04-21

Scientists have found fragments of titanium blasting out of a famous supernova. This discovery, made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, could be a major step in pinpointing exactly how some giant stars explode.

This work is based on Chandra observations of the remains of a supernova called Cassiopeia A (Cas A), located in our galaxy about 11,000 light-years from Earth. This is one of the youngest known supernova remnants, with an age of about 350 years.

For years, scientists have struggled to understand how massive stars - those with masses over about 10 times that of the Sun - explode when they run ...

2021-04-21

The diagnosis of diseases like cancer almost always needs a biopsy - a procedure where a clinician removes a piece of suspect tissue from the body to examine it, typically under a microscope. Many areas of diagnostic medicine, especially cancer management, have seen huge advances in technology, with genetic sequencing, molecular biology and artificial intelligence all rapidly increasing doctors' ability to work out what's wrong with a patient. However the technology of medical needles hasn't changed dramatically in 150 years, and - in the context of cancer management - needles are struggling to provide adequate tissue samples for new diagnostic techniques. Now researchers have shown that modifying the biopsy needle to vibrate rapidly ...

2021-04-21

PHILADELPHIA--Piperlongumine, a chemical compound found in the Indian Long Pepper plant (Piper longum), is known to kill cancerous cells in many tumor types, including brain tumors. Now an international team including researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania has illuminated one way in which the piperlongumine works in animal models -- and has confirmed its strong activity against glioblastoma, one of the least treatable types of brain cancer.

The researchers, whose findings were published this month in END ...

2021-04-21

Scientists have spotted the largest flare ever recorded from the sun's nearest neighbor, the star Proxima Centauri.

The research, which appears today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, was led by the University of Colorado Boulder and could help to shape the hunt for life beyond Earth's solar system.

CU Boulder astrophysicist Meredith MacGregor explained that Proxima Centauri is a small but mighty star. It sits just four light-years or more than 20 trillion miles from our own sun and hosts at least two planets, one of which may look something like ...

2021-04-21

RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. -- With Army funding, scientists invented a way to make compostable plastics break down within a few weeks with just heat and water. This advance will potentially solve waste management challenges at forward operating bases and offer additional technological advances for American Soldiers.

The new process, developed by researchers at University of California, Berkeley and the University of Massachusetts Amherst, involves embedding polyester-eating enzymes in the plastic as it's made.

When exposed to heat and water, an enzyme shrugs off its polymer shroud and starts chomping the plastic polymer into its building blocks -- in the case of biodegradable plastics, which are made primarily of the polyester known as polylactic acid, or PLA, ...

2021-04-21

Women at high risk of breast cancer face cost-associated barriers to care even when they have health insurance, a new study has found.

The findings suggest the need for more transparency in pricing of health care and policies to eliminate financial obstacles to catching cancer early.

The study led by researchers at The Ohio State University included in-depth interviews with 50 women - 30 white, 20 Black - deemed at high risk of breast cancer based on family history and other factors. It appears in the Journal of Genetic Counseling.

The researchers considered it a given that women without any insurance would face serious barriers to preventive care including genetic counseling and testing, prophylactic mastectomy and ...

2021-04-21

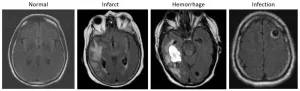

OAK BROOK, Ill. - An artificial intelligence-driven system that automatically combs through brain MRIs for abnormalities could speed care to those who need it most, according to a study published in Radiology: Artificial Intelligence.

MRI produces detailed images of the brain that help radiologists diagnose various diseases and damage from events like a stroke or head injury. Its increasing use has led to an image overload that presents an urgent need for improved radiologic workflow. Automatic identification of abnormal findings in medical images offers a potential solution, enabling improved patient care and accelerated patient discharge.

"There are an increasing number of MRIs that are performed, ...

2021-04-21

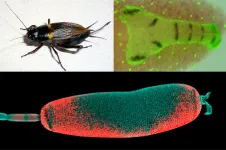

Certain signalling proteins, which are responsible for the development of innate immune function in almost all animals are also required for the formation of the dorsal-ventral (back-belly) axis in insect embryos. A new study by researchers from the University of Cologne's Institute of Zoology suggests that the relevance of these signalling proteins for insect axis formation has increased independently several times during evolution. For example, the research team found similar evolutionary patterns in the Mediterranean field cricket as in the fruit fly Drosophila, although the two insects are only very distantly related and previous observations suggested different evolutionary ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Recolonization of Europe after the last ice age started earlier than previously thought