(Press-News.org) Wildfire smoke can trigger a host of respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms, ranging from runny nose and cough to a potentially life-threatening heart attack or stroke. A new study suggests that the dangers posed by wildfire smoke may also extend to the largest organ in the human body, and our first line of defense against outside threat: the skin.

During the two weeks in November 2018 when wildfire smoke from the Camp Fire choked the San Francisco Bay Area, health clinics in San Francisco saw an uptick in the number of patients visiting with concerns of eczema, also known as atopic dermatitis, and general itch, compared to the same time of the year in 2015 and 2016, the study found.

The findings suggest that even short-term exposure to hazardous air quality from wildfire smoke can be damaging to skin health. The report, carried out by physician researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, in collaboration with researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, appears on April 21 in the journal JAMA Dermatology.

"Existing research on air pollution and health outcomes has focused primarily on cardiac and respiratory health outcomes, and understandably so. But there is a gap in the research connecting air pollution and skin health," said study lead author Raj Fadadu, a student in the UC Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program. "Skin is the largest organ of the human body, and it's in constant interaction with the external environment. So, it makes sense that changes in the external environment, such as increases or decreases in air pollution, could affect our skin health."

Air Pollutants Can Slip through Skin Barriers

Air pollution from wildfires, which consists of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and gases, can impact both normal and eczema-prone skin in a variety of ways. These pollutants often contain chemical compounds that act like keys, allowing them to slip past the skin's outer barrier and penetrate into cells, where they can disrupt gene transcription, trigger oxidative stress or cause inflammation.

Eczema, or atopic dermatitis, is a chronic condition which affects the skin's ability to serve as an effective barrier against environmental factors. Because the skin's barrier has been compromised, people with this condition are prone to flare-ups of red, itchy skin in response to irritants, and may be even more prone to harm from air pollution.

"Skin is a very excellent physical barrier that separates us and protects us from the environment," said study senior author Dr. Maria Wei, a dermatologist and melanoma specialist at UCSF. "However, there are certain skin disorders, such as atopic dermatitis, in which the barrier is not fully functional. It's not normal even when you don't have a rash. So, it would make sense that when exposed to significant air pollution, people with this condition might see an effect on the skin."

Even Short Burst of Air Pollution During the Camp Fire Harms Skin Health

Earlier studies have found a link between atopic dermatitis and air pollution in cities with high background levels of air pollution from cars and industry. However, this is the first study to examine the impacts of a very short burst of extremely hazardous air from wildfires. Despite being located 175 miles away from the Camp Fire, San Francisco saw an approximately nine-fold increase in baseline PM2.5 levels during the time of the blaze.

To conduct the study, the team examined data from more than 8,000 visits to dermatology clinics by both adults and children between October of 2015, 2016 and 2018, and February of the following year. They found that, during the Camp Fire, clinic visits for atopic dermatitis and general itch increased significantly in both adult and pediatric patients.

"Fully 89 percent of the patients that had itch during the time of the Camp Fire did not have a known diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, suggesting that folks with normal skin also experienced irritation and/or absorption of toxins within a very short period of time," Wei said.

While skin conditions like eczema and itch may not be as life-threatening as the respiratory and cardiovascular impacts of wildfire smoke, they can still severely impact people's lives, the researchers say. The study also documented increased rates of prescribed medications, such as steroids, during times of high air pollution, suggesting that patients can experience severe symptoms.

Individuals can protect their skin during wildfire season by staying indoors, wearing clothing that covers the skin if they do go outside, and using emollients, which can strengthen the skin's barrier function. A new medication to treat eczema, called Tapinarof, is now in clinical trials and could also be a useful tool during times of bad air.

"A lot of the conversations about the health implications of climate change and air pollution don't focus on skin health, but it's important to recognize that skin conditions do affect people's quality of life, their social interactions and how they feel psychologically," Fadadu said. "I hope that these health impacts can be more integrated into policies and discussions about the wide-ranging health effects of climate change and air pollution."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors of the paper from UCSF are Barbara Grimes, PhD and Albert T. Young, a MD candidate. From UCB: Nicholas P. Jewell, PhD. Co-authors also include Katrina Abuabara, MD and John R. Balmes, MD, who both have a dual appointment at UCSF and UC Berkeley; and Jason Vargo, PhD of the California Department of Public Health.

Funding: The study was supported by the UCSF Summer Explore Fellowship, the Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association Summer Fellowship, and the UC Berkeley-UCSF Joint Medical Program Thesis Grant. For more funding details, please see the paper.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at END

A mechanistic understanding of brain development requires a systematic survey of neural progenitor cell types, their lineage specification and maturation of postmitotic neurons. Cumulative evidences based on single-cell transcriptomic analysis have revealed the heterogeneity of cortical neural progenitors, their temporal patterning and the developmental trajectories of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the developing neocortex. Nevertheless, the developmental hierarchy of the hypothalamus, which contains an astounding diversity of neurons that regulate endocrine, autonomic and behavioral functions, has not been well understood.

Recently, however, Prof. WU Qingfeng's ...

WHO Peter Libby, MD, cardiovascular medicine specialist at Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Mallinckrodt Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School; author of a new review paper published in Nature.

WHAT Atherosclerosis -- hardening of the arteries -- is now involved in the majority of deaths worldwide, and advances in our understanding of the biology of the disease are changing traditional views and opening up new avenues for treatment.

The picture of who may be at risk for a heart attack has evolved considerably in recent decades. At one time, a heart attack might have conjured up the image of a middle-aged white man with high cholesterol and high blood pressure who smoked cigarettes. Today, traditional concepts of what contributes to risk have changed. These ...

In 2016, an inflatable arch wreaked havoc at the Tour de France bicycle race when it deflated and collapsed on a cyclist, throwing him from his bike and delaying the race while officials scrambled to clear the debris from the road. Officials blamed a passing spectator's wayward belt buckle for the arch's collapse, but the real culprit was physics.

Today's inflatable structures, used for everything from field hospitals to sporting complexes, are monostable, meaning they need a constant input of pressure in order to maintain their inflated state. Lose that pressure and the structure ...

What is the cost of 1 ton of a greenhouse gas? When a climate-warming gas such as carbon dioxide or methane is emitted into the atmosphere, its impacts may be felt years and even decades into the future - in the form of rising sea levels, changes in agricultural productivity, or more extreme weather events, such as droughts, floods, and heat waves. Those impacts are quantified in a metric called the "social cost of carbon," considered a vital tool for making sound and efficient climate policies.

Now a new study by a team including researchers from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) ...

Despite our efforts to sort and recycle, less than 9% of plastic gets recycled in the U.S., and most ends up in landfill or the environment.

Biodegradable plastic bags and containers could help, but if they're not properly sorted, they can contaminate otherwise recyclable #1 and #2 plastics. What's worse, most biodegradable plastics take months to break down, and when they finally do, they form microplastics - tiny bits of plastic that can end up in our oceans, fish, and even our bodies.

Now, as reported in the journal Nature, scientists at the Department ...

A study that appeared today on Current Biology sheds new light on the continental migrations which shaped the genetic background of all present Europeans. The research generates new ancient DNA evidence and direct dating from a fragmentary fossil mandible belonging to an individual who lived ~17,000 years ago in northeastern Italy (Riparo Tagliente, Verona). The results backdate by about 3,000 years the diffusion in Southern Europe of a genetic component linked to Eastern Europe/Western Asia previously believed to have spread westwards during later major warming shifts.

"By looking into the past of this particular individual, ...

Astronomers using data from NASA and the ESA (European Space Agency) telescopes have released a new all-sky map of the outermost region of our galaxy. Known as the galactic halo, this area lies outside the swirling spiral arms that form the Milky Way's recognizable central disk and is sparsely populated with stars. Though the halo may appear mostly empty, it is also predicted to contain a massive reservoir of dark matter, a mysterious and invisible substance thought to make up the bulk of all the mass in the universe.

The data for the new map comes from ESA's Gaia mission and NASA's Near Earth Object Wide Field Infrared Survey Explorer, or NEOWISE, which operated from 2009 to 2013 under the moniker WISE. The study, led by astronomers at the Center for ...

Substantial cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions could be achieved by raising water levels in agricultural peatlands, according to a new study in the journal Nature.

Peatlands occupy just three per cent of the world's land surface area but store a similar amount of carbon to all terrestrial vegetation, as well as supporting unique biodiversity.

In their natural state, they can mitigate climate change by continuously removing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it securely under waterlogged conditions for thousands of years.

But many peatland areas have been substantially modified by human activity, including drainage for agriculture and forest plantations. This results in the ...

Scientists have found fragments of titanium blasting out of a famous supernova. This discovery, made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, could be a major step in pinpointing exactly how some giant stars explode.

This work is based on Chandra observations of the remains of a supernova called Cassiopeia A (Cas A), located in our galaxy about 11,000 light-years from Earth. This is one of the youngest known supernova remnants, with an age of about 350 years.

For years, scientists have struggled to understand how massive stars - those with masses over about 10 times that of the Sun - explode when they run ...

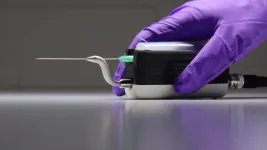

The diagnosis of diseases like cancer almost always needs a biopsy - a procedure where a clinician removes a piece of suspect tissue from the body to examine it, typically under a microscope. Many areas of diagnostic medicine, especially cancer management, have seen huge advances in technology, with genetic sequencing, molecular biology and artificial intelligence all rapidly increasing doctors' ability to work out what's wrong with a patient. However the technology of medical needles hasn't changed dramatically in 150 years, and - in the context of cancer management - needles are struggling to provide adequate tissue samples for new diagnostic techniques. Now researchers have shown that modifying the biopsy needle to vibrate rapidly ...