(Press-News.org) Inspired by nature, the researchers developing a new load-bearing material

Engineers have developed a new material that mimics human cartilage - the body's shock absorbing and lubrication system, and it could herald the development of a new generation of lightweight bearings.

Cartilage is a soft fibrous tissue found around joints which provides protection from the compressive loading generated by walking, running or lifting. It also provides a protective, lubricating layer allowing bones to pass over one another in a frictionless way. For years, scientists have been trying to create a synthetic material with the properties of cartilage.

To date, they have had mixed results.

But in a paper published in the journal Applied Polymer Materials, researchers at the University of Leeds and Imperial College London have announced that they have created a material that functions like cartilage.

The research team believes a cartilage-like material would have a wide-range of uses in engineering.

Cartilage is a bi-phasic porous material, meaning it exists in solid and fluid phases. It switches to its fluid phase by absorbing a viscous substance produced in the joints called synovial fluid. This fluid not only lubricates the joints but when held in the porous matrix of the cartilage, it provides a hydroelastic cushion against compressive forces.

Because the cartilage is porous, the synovial fluid eventually drains away and as it does, it helps dissipate the energy forces travelling through the body, protecting joints from wear and tear and impact injuries. At this point the cartilage returns to its sold phase, ready for the cycle to be repeated.

Dr Siavash Soltanahmadi, Research Fellow in the School of Mechanical Engineering at Leeds, who led the research, said: "Scientists and engineers have been trying for years to develop a material that has the amazing properties of cartilage. We have now developed a material for engineering applications that mimics some of the most important properties found in cartilage, and it has only been possible because we have found a way to mimic the way nature does it.

"There are many applications in engineering for a synthetic material that is soft but can withstand heavy loading with minimum wear and tear, such as in bearings. There is potential across engineering for a material that behaves like cartilage."

Earlier attempts at developing a synthetic cartilage system have focused on the use of hydrogels, materials that absorb water. Hydrogels are good at reducing friction but perform poorly when under compressive force.

One of the problems is that it takes time for the hydrogel to return to its normal shape after it has been compressed.

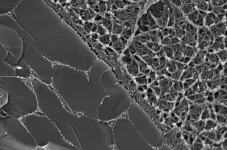

The researchers have overcome this problem by creating a synthetic porous material made of a hydrogel held in a matrix of polydimethylsiloxane or PDMS - a silicone-based polymer. The matrix keeps the shape of the hydrogel.

In the paper, the scientists report that the load-bearing behaviour of the hydrogel held in the PDMS matrix was 14 to 19 times greater than the hydrogel on its own. The equilibrium elastic modulus of the composite was 452 kPa at a strain range of 10%-30%, close to the values reported for the modulus of cartilage tested.

The hydrogel also provided a lubricating layer.

The scientists believe future applications of a new material based on the function of cartilage would challenge many traditional oil-lubricated engineering systems.

Dr Michael Bryant, Associate Professor in the School of Mechanical Engineering, who supervised the research, said; "The ability to use water as an effective lubricant has many applications from energy generation to medical devices. However this often requires a different approach when compared to traditional engineering systems which often use oil-based lubricants and hard-surface coatings.

"This project has helped us to better understand these requirements and develop new tools to address this need."

INFORMATION:

The paper, Fabrication of Cartilage-Inspired Hydrogel/Entangled Polymer-Elastomer Structures Possessing Poro-Elastic Properties, is published in the journal Applied Polymer Materials. (https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acsapm.1c00256)

The research was funded by the Leverhulme Trust - grant number: RPG-2017-281.

Notes to editors

For further details, please contact David Lewis in the press office at the University of Leeds: d.lewis@leeds.ac.uk or on 07710 013287

University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is one of the largest higher education institutions in the UK, with more than 38,000 students from more than 150 different countries, and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universities. The University plays a significant role in the Turing, Rosalind Franklin and Royce Institutes.

We are a top ten university for research and impact power in the UK, according to the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, and are in the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings 2020.

The University was awarded a Gold rating by the Government's Teaching Excellence Framework in 2017, recognising its 'consistently outstanding' teaching and learning provision. Twenty-six of our academics have been awarded National Teaching Fellowships - more than any other institution in England, Northern Ireland and Wales - reflecting the excellence of our teaching.??http://www.leeds.ac.uk?

Several weeks following the publication of the large real-world Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness study by the Clalit Research Institute in Collaboration with Harvard University in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), additional results focusing on vaccine effectiveness in specific sub-populations have now been published.

While the original publication demonstrated the effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine in the general population, outstanding questions remained regarding vaccine effectiveness in specific sub-populations of interest, including the elderly, multi-morbid ...

An international team led by a Skoltech researcher has developed a method of fabrication for biodegradable polymer microcapsules, made more efficient by turning to an unusual source of inspiration - traditional Russian dumpling, or pelmeni, making. The two papers were published in Materials and Design and ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.

Micro-sized capsules, which can be tailored to a variety of purposes, have proven very useful in targeted delivery of drugs and other bioactive compounds. To ensure optimal functioning, these have to be designed and manufactured with precision and in particular shapes, as non-spherical capsules turned out to be more efficient and effective than spherical ones.

"Non-spherical capsules could have side directed release ...

Students who have been exposed to interpersonal trauma — physical assault, sexual assault or unwanted sexual experiences — prior to college are more likely to engage in risky alcohol use. But romantic relationships mitigate these effects of trauma on a student’s drinking behavior, according to a new study led by Virginia Commonwealth University researchers.

The study investigates whether romantic relationships might play a role in mitigating or exacerbating the effects of trauma exposure on alcohol use among college students. It found that students who experienced interpersonal trauma during college consumed more alcohol than those without interpersonal trauma exposure, and that their drinking was more pronounced for those in a relationship with a partner with ...

A good night's sleep is essential for a healthy body and mind, for when we sleep is when the body resets, repairs, and refreshes itself. A lot of people, however, have trouble falling or staying asleep, a condition known as insomnia that affects up to 30% of the population. It is usually caused by an underlying psychiatric or clinical condition and is associated with a poorer quality of life. Recent genome wide analyses have revealed that a gene MEIS1 is linked with insomnia. Interestingly, this gene has also been implicated in restless leg syndrome and iron-deficiency anemia (IDA), the latter ...

For corn, using dairy manure and legume cover crops in crop rotations can reduce the need for inorganic nitrogen fertilizer and protect water quality, but these practices also can contribute to emissions of nitrous oxide -- a potent greenhouse gas.

That is the conclusion of Penn State researchers, who measured nitrous oxide emissions from the corn phases of two crop rotations -- a corn-soybean rotation and a dairy forage rotation -- under three different management regimens. The results of the study offer clues about how dairy farmers might reduce the amount of nitrogen fertilizer they apply to corn crops, saving money and contributing less to climate change.

The results are important because although nitrous ...

SAN FRANCISCO, CA--April 21, 2021--Not all cancer cells within a tumor are created equal; nor do all immune cells (or all liver or brain cells) in your body have the same job. Much of their function depends on their location. Now, researchers at Gladstone Institutes, UC San Francisco (UCSF), and UC Berkeley have developed a more efficient method than ever before to simultaneously map the specialized diversity and spatial location of individual cells within a tissue or a tumor.

The technique, called XYZeq, was described online this week in the journal Science Advances. It involves segmenting a tissue into a microscopic grid before analyzing RNA from intact cells in each square of the grid, in order to gain a clear understanding of how each particular cell is functioning within ...

In rare cases, people who have been fully vaccinated against COVID and are immune to the virus can nevertheless develop the disease. New findings from The Rockefeller University now suggest that these so-called breakthrough cases may be driven by rapid evolution of the virus, and that ongoing testing of immunized individuals will be important to help mitigate future outbreaks.

The research, published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine, reports results from ongoing monitoring within the Rockefeller University community where two fully vaccinated individuals tested positive for the coronavirus. Both had received two doses of either the Moderna or the Pfizer vaccine, with the second dose occurring more than two weeks before the positive test. One person was initially ...

Fast reactions to future events are crucial. A boxer, for example, needs to respond to her opponent in fractions of a second in order to anticipate and block the next attack. Such rapid responses are based on estimates of whether and when events will occur. Now, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics (MPIEA) and New York University (NYU) have identified the cognitive computations underlying this complex predictive behavior.

How does the brain know when to pay attention? Every future event carries two distinct kinds of uncertainty: ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - In the continuing search for dark matter in our universe, scientists believe they have found a unique and powerful detector: exoplanets.

In a new paper, two astrophysicists suggest dark matter could be detected by measuring the effect it has on the temperature of exoplanets, which are planets outside our solar system.

This could provide new insights into dark matter, the mysterious substance that can't be directly observed, but which makes up roughly 80% of the mass of the universe.

"We believe there should be about 300 billion exoplanets that are waiting to be discovered," said Juri Smirnov, a fellow at The Ohio ...

In the arms race "mankind against bacteria", bacteria are currently ahead of us. Our former miracle weapons, antibiotics, are failing more and more frequently when germs use tricky maneuvers to protect themselves from the effects of these drugs. Some species even retreat into the inside of human cells, where they remain "invisible" to the immune system. These particularly dreaded pathogens include multi-resistant staphylococci (MRSA), which can cause life-threatening diseases such as sepsis or pneumonia.

In order to track down the germs in their hidouts and eliminate them, a team of researchers from Empa and ETH Zurich is now developing nanoparticles that use a completely different mode ...