(Press-News.org) In two landmark studies, researchers have used cutting-edge genomic tools to investigate the potential health effects of exposure to ionizing radiation, a known carcinogen, from the 1986 accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in northern Ukraine. One study found no evidence that radiation exposure to parents resulted in new genetic changes being passed from parent to child. The second study documented the genetic changes in the tumors of people who developed thyroid cancer after being exposed as children or fetuses to the radiation released by the accident.

The findings, published around the 35th anniversary of the disaster, are from international teams of investigators led by researchers at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health. The studies were published online in Science on April 22.

"Scientific questions about the effects of radiation on human health have been investigated since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and have been raised again by Chernobyl and by the nuclear accident that followed the tsunami in Fukushima, Japan," said Stephen J. Chanock, M.D., director of NCI's Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (DCEG). "In recent years, advances in DNA sequencing technology have enabled us to begin to address some of the important questions, in part through comprehensive genomic analyses carried out in well-designed epidemiological studies."

The Chernobyl accident exposed millions of people in the surrounding region to radioactive contaminants. Studies have provided much of today's knowledge about cancers caused by radiation exposures from nuclear power plant accidents. The new research builds on this foundation using next-generation DNA sequencing and other genomic characterization tools to analyze biospecimens from people in Ukraine who were affected by the disaster.

The first study investigated the long-standing question of whether radiation exposure results in genetic changes that can be passed from parent to offspring, as has been suggested by some studies in animals. To answer this question, Dr. Chanock and his colleagues analyzed the complete genomes of 130 people born between 1987 and 2002 and their 105 mother-father pairs.

One or both of the parents had been workers who helped clean up from the accident or had been evacuated because they lived in close proximity to the accident site. Each parent was evaluated for protracted exposure to ionizing radiation, which may have occurred through the consumption of contaminated milk (that is, milk from cows that grazed on pastures that had been contaminated by radioactive fallout). The mothers and fathers experienced a range of radiation doses.

The researchers analyzed the genomes of adult children for an increase in a particular type of inherited genetic change known as de novo mutations. De novo mutations are genetic changes that arise randomly in a person's gametes (sperm and eggs) and can be transmitted to their offspring but are not observed in the parents.

For the range of radiation exposures experienced by the parents in the study, there was no evidence from the whole-genome sequencing data of an increase in the number or types of de novo mutations in their children born between 46 weeks and 15 years after the accident. The number of de novo mutations observed in these children were highly similar to those of the general population with comparable characteristics. As a result, the findings suggest that the ionizing radiation exposure from the accident had a minimal, if any, impact on the health of the subsequent generation.

"We view these results as very reassuring for people who were living in Fukushima at the time of the accident in 2011," said Dr. Chanock. "The radiation doses in Japan are known to have been lower than those recorded at Chernobyl."

In the second study, researchers used next-generation sequencing to profile the genetic changes in thyroid cancers that developed in 359 people exposed as children or in utero to ionizing radiation from radioactive iodine (I-131) released by the Chernobyl nuclear accident and in 81 unexposed individuals born more than nine months after the accident. Increased risk of thyroid cancer has been one of the most important adverse health effects observed after the accident.

The energy from ionizing radiation breaks the chemical bonds in DNA, resulting in a number of different types of damage. The new study highlights the importance of a particular kind of DNA damage that involves breaks in both DNA strands in the thyroid tumors. The association between DNA double-strand breaks and radiation exposure was stronger for children exposed at younger ages.

Next, the researchers identified the candidate "drivers" of the cancer in each tumor -- the key genes in which alterations enabled the cancers to grow and survive. They identified the drivers in more than 95% of the tumors. Nearly all the alterations involved genes in the same signaling pathway, called the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, including the genes BRAF, RAS, and RET.

The set of affected genes is similar to what has been reported in previous studies of thyroid cancer. However, the researchers observed a shift in the distribution of the types of mutations in the genes. Specifically, in the Chernobyl study, thyroid cancers that occurred in people exposed to higher radiation doses as children were more likely to result from gene fusions (when both strands of DNA are broken and then the wrong pieces are joined back together), whereas those in unexposed people or those exposed to low levels of radiation were more likely to result from point mutations (single base-pair changes in a key part of a gene).

The results suggest that DNA double-strand breaks may be an early genetic change following exposure to radiation in the environment that subsequently enables the growth of thyroid cancers. Their findings provide a foundation for further studies of radiation-induced cancers, particularly those that involve differences in risk as a function of both dose and age, the researchers added.

"An exciting aspect of this research was the opportunity to link the genomic characteristics of the tumor with information about the radiation dose -- the risk factor that potentially caused the cancer," said Lindsay M. Morton, Ph.D., deputy chief of the Radiation Epidemiology Branch in DCEG, who led the study.

"The Cancer Genome Atlas set the standard for how to comprehensively profile tumor characteristics," Dr. Morton continued. "We extended that approach to complete the first large genomic landscape study in which the potential carcinogenic exposure was well-characterized, enabling us to investigate the relationship between specific tumor characteristics and radiation dose."

She noted that the study was made possible by the creation of the Chernobyl Tissue Bank about two decades ago -- long before the technology had been developed to conduct the kind of genomic and molecular studies that are common today.

"These studies represent the first time our group has done molecular studies using the biospecimens that were collected by our colleagues in Ukraine," Dr. Morton said. "The tissue bank was set up by visionary scientists to collect tumor samples from residents in highly contaminated regions who developed thyroid cancer. These scientists recognized that there would be substantial advances in technology in the future, and the research community is now benefiting from their foresight."

INFORMATION:

About the National Cancer Institute (NCI): NCI leads the National Cancer Program and NIH's efforts to dramatically reduce the prevalence of cancer and improve the lives of cancer patients and their families, through research into prevention and cancer biology, the development of new interventions, and the training and mentoring of new researchers. For more information about cancer, please visit the NCI website at END

Researchers have found that a natural molecule can effectively block the binding of a subset of human antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. The discovery may help explain why some COVID-19 patients can become severely ill despite having high levels of antibodies against the virus.

In their research, published in Science Advances today (22 April 2021), teams from the Francis Crick Institute, in collaboration with researchers at Imperial College London, Kings College London and UCL (University College London), found that biliverdin and bilirubin, natural molecules present in the body, can suppress the ...

Researchers have identified another potential target for neutralizing antibodies on the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein that is masked by metabolites in the blood. As a result of this masking, the target may be inaccessible to antibodies, because they must compete with metabolite molecules to bind to the otherwise open region, the study authors speculate. This competitive binding activity may represent another method of immune evasion by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Although further validation work is needed, the findings suggest that strategies to unmask this region - thus making it more visible and accessible to antibodies - may help lead to new vaccine designs. ...

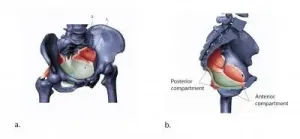

AUSTIN, Texas -- Despite advances in medicine and technology, childbirth isn't likely to get much easier on women from a biological perspective.

Engineers at The University of Texas at Austin and University of Vienna revealed in new research a series of evolutionary trade-offs that have created a near-perfect balance between supporting childbirth and keeping organs intact on a day-to-day basis. Human reproduction is unique because of the comparatively tight fit between the birth canal and baby's head, and it is likely to stay that way because of these competing biological imperatives.

The size of the pelvic floor and canal is key to keeping this balance. These opposing duties have constrained the ability of the pelvic floor to evolve over time to make childbirth easier because doing ...

Not all cancerous tumors are created equal. Some tumors, known as "hot" tumors, show signs of inflammation, which means they are infiltrated with T cells working to fight the cancer. Those tumors are easier to treat, as immunotherapy drugs can then amp up the immune response.

"Cold" tumors, on the other hand, have no T-cell infiltration, which means the immune system is not stepping in to help. With these tumors, immunotherapy is of little use.

It's the latter type of tumor that researchers Michael Knitz and radiation oncologist and University of Colorado Cancer Center member Sana Karam, MD, PhD, address in new research published this week in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. Working with mouse models in Karam's specialty area of head and neck cancers, Knitz and ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- As NASA's Perseverance rover begins its search for ancient life on the surface of Mars, a new study suggests that the Martian subsurface might be a good place to look for possible present-day life on the Red Planet.

The study, published in the journal Astrobiology, looked at the chemical composition of Martian meteorites -- rocks blasted off of the surface of Mars that eventually landed on Earth. The analysis determined that those rocks, if in consistent contact with water, would produce the chemical energy needed to support microbial communities similar to those that survive in the unlit depths of the Earth. Because these meteorites may be representative ...

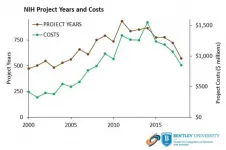

The unprecedented development of COVID-19 vaccines less than a year after discovery of this virus was enabled by more than $17 billion of research on vaccine technologies funded by the NIH prior to the pandemic, according to new research from Bentley University's Center for Integration of Science and Industry. The article, titled "NIH funding for vaccine readiness before the COVID-19 pandemic," demonstrates the critical role this broad foundation of government-funded research plays in ensuring vaccine readiness.

The report, published today in the journal Vaccine, ...

DALLAS - April 22, 2021 - Being Black or Hispanic, living in high-poverty neighborhoods, and having Medicaid or no insurance coverage are associated with higher mortality in men and women under 40 with cancer, a review by UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers found.

"Survival is not different because of biology. It's not different because of patient-level factors," says Caitlin Murphy, Ph.D., lead author of the study and an assistant professor of population and data sciences and internal medicine at UT Southwestern. "No matter which way we looked at the data, we still saw consistent and alarming differences in survival by race - and these are teens and young adults."

Other findings based on an ...

Machine learning could provide up an extra hour of warning time for debris flows along the Illgraben torrent in Switzerland, researchers report at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)'s 2021 Annual Meeting.

Debris flows are mixtures of water, sediment and rock that move rapidly down steep hills, triggered by heavy precipitation and often containing tens of thousands of cubic meters of material. Their destructive potential makes it important to have monitoring and warning systems in place to protect nearby people and infrastructure.

In her presentation at SSA, Ma?gorzata Chmiel of ETH Zürich described a machine learning approach to detecting and alerting against debris flows for the Illgraben torrent, a site in the European Alps that experiences significant debris flows and torrential ...

It seems like a smooth slab of stainless steel, but look a little closer, and you'll see a simplified cross-section of the Los Angeles sedimentary basin.

Caltech researcher Sunyoung Park and her colleagues are printing 3D models like the metal Los Angeles proxy to provide a novel platform for seismic experiments. By printing a model that replicates a basin's edge or the rise and fall of a topographic feature and directing laser light at it, Park can simulate and record how seismic waves might pass through the real Earth.

In her presentation at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)'s 2021 Annual Meeting, Park explained why these physical models can address some of the drawbacks of numerical modeling of ground motion in some cases.

Small-scale, complex structures in ...

Days after the 4 August 2020 massive explosion at the port of Beirut in Lebanon, researchers were on the ground mapping the impacts of the explosion in the port and surrounding city.

The goal was to document and preserve data on structural and façade damage before rebuilding, said University of California, Los Angeles civil and environmental engineer Jonathan Stewart, who spoke about the effort at the Seismological Society of America (SSA)'s 2021 Annual Meeting.

The effort also provided an opportunity to compare NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory satellite surveys of the blast effects with data collected from the ground surveys. Stewart and his colleagues concluded that satellite-based Damage Proxy Maps were effective at identifying severely damaged buildings and undamaged ...