(Press-News.org) Researchers have big ideas for the potential of quantum technology, from unhackable networks to earthquake sensors. But all these things depend on a major technological feat: being able to build and control systems of quantum particles, which are among the smallest objects in the universe.

That goal is now a step closer with the publication of a new method by University of Chicago scientists. Published April 28 in Nature, the paper shows how to bring multiple molecules at once into a single quantum state--one of the most important goals in quantum physics.

"People have been trying to do this for decades, so we're very excited," said senior author Cheng Chin, a professor of physics at UChicago who said he has wanted to achieve this goal since he was a graduate student in the 1990s. "I hope this can open new fields in many-body quantum chemistry. There's evidence that there are a lot of discoveries waiting out there."

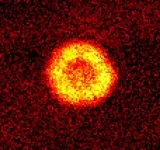

One of the essential states of matter is called a Bose-Einstein condensate: When a group of particles cooled to nearly absolute zero share a quantum state, the entire group starts behaving as though it were a single atom. It's a bit like coaxing an entire band to march entirely in step while playing in tune--difficult to achieve, but when it happens, a whole new world of possibilities can open up.

Scientists have been able to do this with atoms for a few decades, but what they'd really like to do is to be able to do it with molecules. Such a breakthrough could serve as the underpinning for many forms of quantum technology.

But because molecules are larger than atoms and have many more moving parts, most attempts to harness them have dissolved into chaos. "Atoms are simple spherical objects, whereas molecules can vibrate, rotate, carry small magnets," said Chin. "Because molecules can do so many different things, it makes them more useful, and at the same time much harder to control."

Chin's group wanted to take advantage of a few new capabilities in the lab that had recently become available. Last year, they began experimenting with adding two conditions.

The first was cooling the entire system down even further--down to 10 nanokelvins, a split hair above absolute zero. Then they packed the molecules into a crawl space so that they were pinned flat. "Typically, molecules want to move in all directions, and if you allow that, they are much less stable," said Chin. "We confined the molecules so that they are on a 2D surface and can only move in two directions."

The result was a set of virtually identical molecules--lined up with exactly the same orientation, the same vibrational frequency, in the same quantum state.

The scientists described this molecular condensate as like a pristine sheet of new drawing paper for quantum engineering. "It's the absolute ideal starting point," Chin said. "For example, if you want to build quantum systems to hold information, you need a clean slate to write on before you can format and store that information."

So far, they've been able to link up to a few thousand molecules together in such a state, and are beginning to explore its potential.

"In the traditional way to think about chemistry, you think about a few atoms and molecules colliding and forming a new molecule," Chin said. "But in the quantum regime, all molecules act together, in collective behavior. This opens a whole new way to explore how molecules can all react together to become a new kind of molecule.

"This has been a goal of mine since I was a student," he added, "so we're very, very happy about this result."

INFORMATION:

The first author on the study was graduate student Zhendong Zhang; the other two authors were Shanxi University's Liangchao Chen (formerly a visiting scholar at UChicago) and graduate student Kaixuan Yao.

Citation: "Atomic Bose-Einstein condensate to molecular Bose-Einstein condensate transition." Zhang, Chen, Yao and Chin, Nature, April 28, 2021.

Funding: National Science Foundation, Army Research Office, University of Chicago Materials Research Science and Engineering Center.

PITTSBURGH, April 28, 2021 - It is not every day that scientists come across a phenomenon so fundamental that it is observed across fruit flies, rodents and humans.

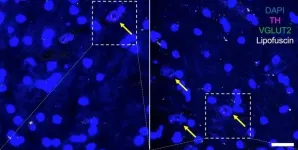

In a paper published today in Aging Cell, neuroscientists from the University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences discovered that a single protein--a glutamate transporter on the membrane of vesicles that carry dopamine in neurons--is key to regulating sex differences in the brain's vulnerability to age-related neuron loss.

The protein--named VGLUT--was more abundant in dopamine neurons of female fruit flies, rodents and human beings than in males, correlating with females' greater resilience to age-related neuron loss and mobility deficiencies, the researchers found. Excitingly, ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- A multidecade study of young adults living in the United Kingdom has found higher rates of mental illness symptoms among those exposed to higher levels of traffic-related air pollutants, particularly nitrogen oxides, during childhood and adolescence.

Previous studies have identified a link between air pollution and the risk of specific mental disorders, including depression and anxiety, but this study looked at changes in mental health that span all forms of disorder and psychological distress associated with exposure to traffic-related air pollutants.

The findings, which will appear April ...

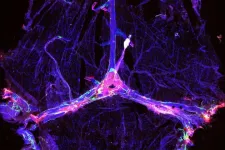

Experimental Alzheimer's drugs have shown little success in slowing declines in memory and thinking, leaving scientists searching for explanations. But new research in mice has shown that some investigational Alzheimer's therapies are more effective when paired with a treatment geared toward improving drainage of fluid -- and debris -- from the brain, according to a study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The findings, published April 28 in the journal Nature, suggest that the brain's drainage system -- known as the meningeal lymphatics -- plays a pivotal but underappreciated role in neurodegenerative disease, and that repairing faulty drains could be a key to unlocking the potential of certain Alzheimer's therapies.

"The ...

Is forest harvesting increasing in Europe? Yes, but not as much as reported last July in a controversial study published in Nature.

The study Abrupt increase in harvested forest area over Europe after 2015, used satellite data to assess forest cover and claimed an abrupt increase of 69% in the harvested forest in Europe from 2016. The authors, from the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC), suggested that this increase resulted from expanding wood markets encouraged by EU bioeconomy and bioenergy policies. The publication triggered a heated debate, both scientific ...

What The Study Did: Length, readability and complexity of informed consent documents for the COVID-19 vaccine phase III randomized clinical trials were assessed in this quality improvement study.

Authors: Ezekiel J. Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10843)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author ...

What The Study Did: The number of applicants and number of applications submitted per applicant to internal medicine residency and subspecialty fellowships for 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared with five prior application cycles in this study.

Authors: Laura A. Huppert, M.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8199)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated racial/ethnic differences in the performance of statistical models that use health record data to predict the risk of suicide after an outpatient mental health visit.

Authors: R. Yates Coley, Ph.D., of the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0493)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest ...

What The Study Did: The association between undergoing gender-affirming surgery and mental health outcomes was looked at in this study.

Authors: Anthony N. Almazan, B.A., of Harvard Medical School in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0952)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study and commentary ...

Enhancing the brain's lymphatic system when administering immunotherapies may lead to better clinical outcomes for Alzheimer's disease patients, according to a new study in mice. Results published April 28 in Nature suggest that treatments such as the immunotherapies BAN2401 or aducanumab might be more effective when the brain's lymphatic system can better drain the amyloid-beta protein that accumulates in the brains of those living with Alzheimer's. Major funding for the research was provided by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), part of the National Institutes of Health, and all study data is now freely available ...

For the first time, scientists are able to study changes in the DNA of any human tissue, following the resolution of long-standing technical challenges by scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. The new method, called nanorate sequencing (NanoSeq), makes it possible to study how genetic changes occur in human tissues with unprecedented accuracy.

The study, published today (28 April) in Nature, represents a major advance for research into cancer and ageing. Using NanoSeq to study samples of blood, colon, brain and muscle, the research also challenges the idea that cell division is the main mechanism ...