Soil bacteria evolve with climate change

2021-04-28

(Press-News.org) While evolution is normally thought of as occurring over millions of years, researchers at the University of California, Irvine have discovered that bacteria can evolve in response to climate change in 18 months. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, biologists from UCI found that evolution is one way that soil microbes might deal with global warming.

Soil microbiomes - the collection of bacteria and other microbes in soil - are a critical engine of the global carbon cycle; microbes decompose the dead plant material to recycle nutrients back into the ecosystem and release carbon back into the atmosphere. Multiple environmental factors influence the composition and functioning of soil microbiomes, but these responses are usually studied from an ecological perspective, asking which microbial species increase or decrease in abundance as environmental conditions change. In the current study, the UCI team investigated if bacterial species in the soil also evolve when their environment changes.

"We know that evolution can occur very fast in bacteria, as in response to antibiotics, but we do not know how important evolution might be for bacteria in the environment with ongoing climate change," said Dr. Alex Chase, the lead author of the study and a former graduate student at UCI.

Several inherent characteristics should enable soil microbes to adapt rapidly to new climate conditions. Microbes are abundant and can reproduce in only hours, so a rare genetic mutation that allows for adaptation to new climate conditions might occur by chance over a short time frame. However, most of what is known about bacterial evolution is from controlled laboratory experiments, where bacteria are grown in flasks with artificial food. It was unclear whether evolution happens fast enough in soils to be relevant to the effects of current rates of climate change.

"Current predictions about how climate change will affect microbiomes make the assumption that microbial species are static. We therefore wanted to test whether bacteria can evolve rapidly in natural settings such as soil," explained Dr. Chase.

To measure evolution in a natural environment, the researchers deployed a first-ever bacterial evolution experiment in the field, using a soil bacterium called Curtobacterium. The researchers used 125 "microbial cages" filled with microbial food made up of dead plant material. (The cages allow the transport of water, but not other microbes.) The cages then exposed the bacteria to a range of climate conditions across an elevation gradient in Southern California. The team conducted two parallel experiments over 18 months measuring both the ecological and evolutionary responses in the bacteria.

"The microbial cages allowed us to control the types of bacteria that were present, while exposing them to different environmental conditions in different sites. We could then test, for instance, how the warm and arid conditions of the desert site affected the genetic diversity of a single Curtobacterium species," said Dr. Chase.

After 18 months, the scientists sequenced bacterial DNA from the microbial cages of the experiments. In the first experiment containing a diverse soil microbiome, different Curtobacterium species changed in abundance, an expected ecological response. In the second experiment over the same time frame, the genetic diversity of a single Curtobacterium bacterium changed, revealing an evolutionary response to the same environmental conditions. The authors conclude that both ecological and evolutionary processes have the potential to contribute to how a soil microbiome responds to changing climate conditions.

"The study shows that we can observe rapid evolution in soil microbes, and this is an exciting achievement. Our next goal is to understand the importance of evolutionary adaptation for soil ecosystems under future climate change," said co-author Jennifer Martiny, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology who co-directs the UCI Microbiome Initiative.

INFORMATION:

Researchers who contributed to this work were: Alexander Chase, Claudia Weihe, and Jennifer Martiny.

The study was supported by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography Postdoctoral Scholar Fellowship, the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research.

About the University of California, Irvine: Founded in 1965, UCI is the youngest member of the prestigious Association of American Universities and is ranked among the nation's top 10 public universities by U.S. News & World Report. The campus has produced three Nobel laureates and is known for its academic achievement, premier research, innovation and anteater mascot. Led by Chancellor Howard Gillman, UCI has more than 36,000 students and offers 224 degree programs. It's located in one of the world's safest and most economically vibrant communities and is Orange County's second-largest employer, contributing $7 billion annually to the local economy and $8 billion statewide. For more on UCI, visit http://www.uci.edu.

Media access: Radio programs/stations may, for a fee, use an on-campus ISDN line to interview UCI faculty and experts, subject to availability and university approval. For more UCI news, visit news.uci.edu. Additional resources for journalists may be found at communications.uci.edu/for-journalists.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-04-28

The neurotransmitter noradrenaline, which plays a key role in the fight-or-flight stress response, impairs immune responses by inhibiting the movements of various white blood cells in different tissues, researchers report April 28th in the journal Immunity. The fast and transient effect occurred in mice with infections and cancer, but for now, it's unclear whether the findings generalize to humans with various health conditions.

"We found that stress can cause immune cells to stop moving and prevents immune cells from protecting against disease," says senior study author University of Melbourne's Scott Mueller (@SMuellerLab) of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute). "This is novel because it was not known that ...

2021-04-28

Psychedelic drugs have shown promise for treating neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. However, due to their hallucinatory side effects, some researchers are trying to identify drugs that could offer the benefits of psychedelics without causing hallucinations. In the journal Cell on April 28, researchers report they have identified one such drug through the development of a genetically encoded fluorescent sensor--called psychLight--that can screen for hallucinogenic potential by indicating when a compound activates the serotonin 2A receptor.

"Serotonin reuptake inhibitors have long been used for treating depression, but we don't ...

2021-04-28

A genetically encoded sensor to detect hallucinogenic compounds has been developed by researchers at the University of California, Davis. Named psychLight, the sensor could be used in discovering new treatments for mental illness, in neuroscience research and to detect drugs of abuse. The work is published April 28 in the journal Cell.

Compounds related to psychedelic drugs such as LSD and dimethyltryptamine (DMT) show great promise for treating disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorder. These drugs are called psychoplastogens ...

2021-04-28

It's one of the most audacious projects in biology today - reading the entire genome of every bird, mammal, lizard, fish, and all other creatures with backbones.

And now comes the first major payoff from the Vertebrate Genome Project (VGP): near complete, high-quality genomes of 25 species, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigator Erich Jarvis with scores of coauthors report April 28, 2021, in the journal Nature. These species include the greater horseshoe bat, the Canada lynx, the platypus, and the kākāp? parrot - one of the first high-quality ...

2021-04-28

Researchers have big ideas for the potential of quantum technology, from unhackable networks to earthquake sensors. But all these things depend on a major technological feat: being able to build and control systems of quantum particles, which are among the smallest objects in the universe.

That goal is now a step closer with the publication of a new method by University of Chicago scientists. Published April 28 in Nature, the paper shows how to bring multiple molecules at once into a single quantum state--one of the most important goals in quantum physics.

"People have been trying to do this for decades, so we're very excited," said senior author Cheng Chin, a professor of physics at UChicago who said he has wanted ...

2021-04-28

PITTSBURGH, April 28, 2021 - It is not every day that scientists come across a phenomenon so fundamental that it is observed across fruit flies, rodents and humans.

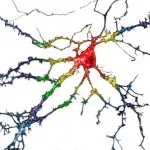

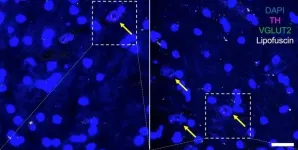

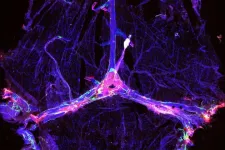

In a paper published today in Aging Cell, neuroscientists from the University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences discovered that a single protein--a glutamate transporter on the membrane of vesicles that carry dopamine in neurons--is key to regulating sex differences in the brain's vulnerability to age-related neuron loss.

The protein--named VGLUT--was more abundant in dopamine neurons of female fruit flies, rodents and human beings than in males, correlating with females' greater resilience to age-related neuron loss and mobility deficiencies, the researchers found. Excitingly, ...

2021-04-28

DURHAM, N.C. -- A multidecade study of young adults living in the United Kingdom has found higher rates of mental illness symptoms among those exposed to higher levels of traffic-related air pollutants, particularly nitrogen oxides, during childhood and adolescence.

Previous studies have identified a link between air pollution and the risk of specific mental disorders, including depression and anxiety, but this study looked at changes in mental health that span all forms of disorder and psychological distress associated with exposure to traffic-related air pollutants.

The findings, which will appear April ...

2021-04-28

Experimental Alzheimer's drugs have shown little success in slowing declines in memory and thinking, leaving scientists searching for explanations. But new research in mice has shown that some investigational Alzheimer's therapies are more effective when paired with a treatment geared toward improving drainage of fluid -- and debris -- from the brain, according to a study led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The findings, published April 28 in the journal Nature, suggest that the brain's drainage system -- known as the meningeal lymphatics -- plays a pivotal but underappreciated role in neurodegenerative disease, and that repairing faulty drains could be a key to unlocking the potential of certain Alzheimer's therapies.

"The ...

2021-04-28

Is forest harvesting increasing in Europe? Yes, but not as much as reported last July in a controversial study published in Nature.

The study Abrupt increase in harvested forest area over Europe after 2015, used satellite data to assess forest cover and claimed an abrupt increase of 69% in the harvested forest in Europe from 2016. The authors, from the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC), suggested that this increase resulted from expanding wood markets encouraged by EU bioeconomy and bioenergy policies. The publication triggered a heated debate, both scientific ...

2021-04-28

What The Study Did: Length, readability and complexity of informed consent documents for the COVID-19 vaccine phase III randomized clinical trials were assessed in this quality improvement study.

Authors: Ezekiel J. Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10843)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Soil bacteria evolve with climate change