Alternative gene editing techniques called recombineering instead perform this bait-and-switch by introducing an alternate piece of DNA while a cell is replicating its genome, efficiently creating genetic mutations without breaking DNA. These methods are simple enough that they can be used in many cells at once to create complex pools of mutations for researchers to study. Figuring out what the effects of those mutations are, however, requires that each mutant be isolated, sequenced, and characterized: a time-consuming and impractical task.

Researchers at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and Harvard Medical School (HMS) have created a new gene editing tool called Retron Library Recombineering (RLR) that makes this task easier. RLR generates up to millions of mutations simultaneously, and "barcodes" mutant cells so that the entire pool can be screened at once, enabling massive amounts of data to be easily generated and analyzed. The achievement, which has been accomplished in bacterial cells, is described in a recent paper in PNAS.

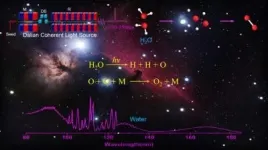

"RLR enabled us to do something that's impossible to do with CRISPR: we randomly chopped up a bacterial genome, turned those genetic fragments into single-stranded DNA in situ, and used them to screen millions of sequences simultaneously," said co-first author Max Schubert, Ph.D., a postdoc in the lab of Wyss Core Faculty member George Church, Ph.D. "RLR is a simpler, more flexible gene editing tool that can be used for highly multiplexed experiments, which eliminates the toxicity often observed with CRISPR and improves researchers' ability to explore mutations at the genome level."

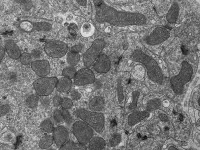

Retrons: from enigma to engineering tool Retrons are segments of bacterial DNA that undergo reverse transcription to produce fragments of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). Retrons' existence has been known for decades, but the function of the ssDNA they produce flummoxed scientists from the 1980s until June 2020, when a team finally figured out that retron ssDNA detects whether a virus has infected the cell, forming part of the bacterial immune system.

While retrons were originally seen as simply a mysterious quirk of bacteria, researchers have become more interested in them over the last few years because they, like CRISPR, could be used for precise and flexible gene editing in bacteria, yeast, and even human cells. "For a long time, CRISPR was just considered a weird thing that bacteria did, and figuring out how to harness it for genome engineering changed the world. Retrons are another bacterial innovation that might also provide some important advances," said Schubert. His interest in retrons was piqued several years ago because of their ability to produce ssDNA in bacteria - an attractive feature for use in a gene editing process called oligonucleotide recombineering.

Recombination-based gene editing techniques require integrating ssDNA containing a desired mutation into an organism's DNA, which can be done in one of two ways. Double-stranded DNA can be physically cut (with CRISPR-Cas9, for example) to induce the cell to incorporate the mutant sequence into its genome during the repair process, or the mutant DNA strand and a single-stranded annealing protein (SSAP) can be introduced into a cell that is replicating so that the SSAP incorporates the mutant strand into the daughter cells' DNA.

"We figured that retrons should give us the ability to produce ssDNA within the cells we want to edit rather than trying to force them into the cell from the outside, and without damaging the native DNA, which were both very compelling qualities," said co-first author Daniel Goodman, Ph.D., a former Graduate Research Fellow at the Wyss Institute who is now a Jane Coffin Childs Postdoctoral Fellow at UCSF.

Another attraction of retrons is that their sequences themselves can serve as "barcodes" that identify which individuals within a pool of bacteria have received each retron sequence, enabling dramatically faster, pooled screens of precisely-created mutant strains.

To see if they could actually use retrons to achieve efficient recombineering with retrons, Schubert and his colleagues first created circular plasmids of bacterial DNA that contained antibiotic resistance genes placed within retron sequences, as well as an SSAP gene to enable integration of the retron sequence into the bacterial genome. They inserted these retron plasmids into E. coli bacteria to see if the genes were successfully integrated into their genomes after 20 generations of cell replication. Initially, less than 0.1% of E. coli bearing the retron recombineering system incorporated the desired mutation.

To improve this disappointing initial performance, the team made several genetic tweaks to the bacteria. First, they inactivated the cells' natural mismatch repair machinery, which corrects DNA replication errors and could therefore be "fixing" the desired mutations before they were able to be passed on to the next generation. They also inactivated two bacterial genes that code for exonucleases - enzymes that destroy free-floating ssDNA. These changes dramatically increased the proportion of bacteria that incorporated the retron sequence, to more than 90% of the population.

Name tags for mutants Now that they were confident that their retron ssDNA was incorporated into their bacteria's genomes, the team tested whether they could use the retrons as a genetic sequencing "shortcut," enabling many experiments to be performed in a mixture. Because each plasmid had its own unique retron sequence that can function as a "name tag", they reasoned that they should be able to sequence the much shorter retron rather than the whole bacterial genome to determine which mutation the cells had received.

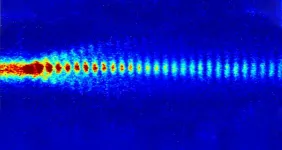

First, the team tested whether RLR could detect known antibiotic resistance mutations in E coli. They found that it could - retron sequences containing these mutations were present in much greater proportions in their sequencing data compared with other mutations. The team also determined that RLR was sensitive and precise enough to measure small differences in resistance that result from very similar mutations. Crucially, gathering these data by sequencing barcodes from the entire pool of bacteria rather than isolating and sequencing individual mutants, dramatically speeds up the process.

Then, the researchers took RLR one step further to see if it could be used on randomly-fragmented DNA, and find out how many retrons they could use at once. They chopped up the genome of a strain of E. coli highly resistant to another antibiotic, and used those fragments to build a library of tens of millions of genetic sequences contained within retron sequences in plasmids. "The simplicity of RLR really shone in this experiment, because it allowed us to build a much bigger library than what we can currently use with CRISPR, in which we have to synthesize both a guide and a donor DNA sequence to induce each mutation," said Schubert.

This library was then introduced into the RLR-optimized E coli strain for analysis. Once again, the researchers found that retrons conferring antibiotic resistance could be easily identified by the fact that they were enriched relative to others when the pool of bacteria was sequenced.

"Being able to analyze pooled, barcoded mutant libraries with RLR enables millions of experiments to be performed simultaneously, allowing us to observe the effects of mutations across the genome, as well as how those mutations might interact with each other," said senior author George Church, who leads the Wyss Institute's Synthetic Biology Focus Area and is also a Professor of Genetics at HMS. "This work helps establish a road map toward using RLR in other genetic systems, which opens up many exciting possibilities for future genetic research."

Another feature that distinguishes RLR from CRISPR is that the proportion of bacteria that successfully integrate a desired mutation into their genome increases over time as the bacteria replicate, whereas CRISPR's "one shot" method tends to either succeed or fail on the first try. RLR could potentially be combined with CRISPR to improve its editing performance, or could be used as an alternative in the many systems in which CRISPR is toxic.

More work remains to be done on RLR to improve and standardize editing rate, but excitement is growing about this new tool. RLR's simple, streamlined nature could enable the study of how multiple mutations interact with each other, and the generation of a large number of data points that could enable the use of machine learning to predict further mutational effects.

"This new synthetic biology tool brings genome engineering to an even higher levels of throughput, which will undoubtedly lead to new, exciting, and unexpected innovations," said Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., the Wyss Institute's Founding Director. Ingber is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at HMS and Boston Children's Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

INFORMATION:

Additional authors of the paper include Timothy Wannier from HMS, Divjot Kaur from the University of Warwick, Fahim Farzadfard and Timothy Lu from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Seth Shipman from the Gladstone Institute of Data Science and Biotechnology.

This research was supported by the United States Department of Energy (DE-FG02-02ER63445) and by the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship.