In a study led by a University of Central Florida researcher and published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, researchers presented evidence of baby green sea turtles arriving at the Sargasso Sea after entering the ocean off the east coast of Florida.

The study was the first time that green sea turtles have been tracked during their early "lost years," which is defined as the time between hatching from their nests along Florida's Atlantic coast and heading into the ocean and their "teenage years," when they return to coastal habitats after several years in the open ocean. Not much is known about where sea turtles go during these years, which is where the "lost years" description comes from. The new findings echo the team's previous research that showed baby loggerhead sea turtles arrive at the Sargasso Sea.

The results are helping to solve the mystery of where the turtles go and will also inform efforts to conserve the threatened animals, especially during their delicate first years at sea.

Florida's Atlantic coastline is a major nesting area for green and loggerhead sea turtles, which are iconic species in conservation efforts and important for their role in helping maintain ocean ecosystems, says UCF Biology Associate Professor Kate Mansfield, who led the study in collaboration with Jeanette Wyneken at Florida Atlantic University.

Scientists have long assumed that after hatching and going into the ocean, baby sea turtles would passively drift in sea currents, such as those circulating around the Atlantic Ocean, and ride those currents until their later juvenile years.

"That green turtles and loggerheads would continue in the currents, but that some might leave the currents and go into the Sargasso Sea was not ever considered or predicted by long-held hypotheses and the assumptions in the field," Mansfield says. "We found that the green turtles actively oriented to go into the Sargasso Sea and in even greater numbers than the loggerheads tracked in our earlier work. Granted, our sample sizes aren't huge, but enough turtles made this journey that it really throws into question our long-held beliefs about the early lives of sea turtles."

The Sargasso Sea, located off the east coast of the U.S. in the North Atlantic Ocean, has often been featured erroneously in popular culture, such as in Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, as a place where ships could become derelict when trying to travel through thick mats of the floating, brown, Sargassum algae for which it is named. In reality, the Sargassum algae clumps together in distinct patches so it poses little threat to vessels navigating through the area.

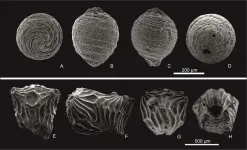

The researchers were able to track the turtles by attaching advanced, solar-powered tracking devices, about an inch in length, to their shells. This also required determining the optimum adhesive for applying the sensor, which was different for the green sea turtles than for loggerheads because of the greens' waxier-feeling shells. The tracking device is designed to fall off after a few months and does not hurt the turtles or inhibit the turtles' shell growth or behavior, Mansfield says.

In the current study, 21 green sea turtles less than a year old, had transmitters affixed and were released into the Gulf Stream ocean currents about 10 miles offshore from the beach where they were born. The turtle release dates were from 2012 to 2013, and the researchers were able to track the turtles for up to 152 days.

Of the 21 turtles, 14 departed the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic gyre of circulating currents and entered the western or northern Sargasso Sea region in the western Atlantic Ocean, according to the study. This is compared to seven out of 17 loggerhead turtles that left the Gulf Stream and entered the Sargasso Sea in the previous study.

Wyneken, a professor of biological sciences and director of Florida Atlantic University's Marine Science Laboratory at Gumbo Limbo Environmental Complex, worked with Mansfield to collect, raise, tag and release the turtles. She says the research is important because it sheds light on where the baby turtles go during a delicate period in their lives.

"These studies in which we learn where little sea turtles go to start growing up are fundamental to sound sea turtle conservation," Wyneken says. "If we don't know where they are and what parts of the ocean are important to them, we are doing conservation blindfolded."

Jiangang Luo, PhD, a scientist with the Tarpon Bonefish Research Center at the University of Miami's Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and study co-author, has a background in mathematical biology, oceanography and advanced scientific data visualization. As part of the research team, he helped process and analyze the data and graphed and animated the results.

"It feels great to see how the little turtles are traveling and utilizing the ocean," Luo says. "The ocean is our future, and we must have the ocean to save the sea turtles." The Sargasso Sea Commission, which works as a steward for the area with support from multiple governments and collaborating partners, will use data from the research as part of its upcoming ecosystem diagnostic project, says the commission's Programme Manager Teresa Mackey.

The project will quantify threats and their potential impact on the Sargasso Sea, including climate change, plastics pollution and commercial activities, as well as investigate ways to counter challenges the area faces and establish a baseline for ongoing monitoring and adaptive management.

"Dr. Mansfield's research into the critical habitat that this area provides for turtles early in their life cycle gives concrete evidence of the importance of the Sargasso Sea for endangered and critically endangered species and is one of the many reasons why conservation of this high-seas ecosystem is vitally important for marine biodiversity," Mackey says.

UCF's Marine Turtle Research Group, which Mansfield directs, has been one of the commission's collaborators since 2017.

Mansfield says next steps for the "lost years" research will include looking more closely at differences in orientation and swimming behavior between turtle species, understanding the role Sargassum plays in early sea turtle development, and testing newer, smaller, and more accurate tracking devices to learn more about the places the baby turtles go and how they interact with their environment.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded largely through the Florida Sea Turtle Specialty License Plate grants program, Disney Conservation Fund and the Save Our Seas Foundation.

Mansfield received her doctorate in marine science from William & Mary University's Virginia Institute of Marine Science. She joined UCF's Department of Biology, part of UCF's College of Sciences, in 2013. In addition to directing UCF's Marine Turtle Research Group, Mansfield is a member of UCF's Sustainable Coastal Systems cluster and National Center for Integrated Coastal Research. For the latest updates and to learn more about UCF's Marine Turtle Research Group, follow them at @UCFTurtleLab on Twitter and Instagram.

CONTACT: Robert H. Wells, Office of Research, robert.wells@ucf.edu