(Press-News.org) Researchers from the UCLA School of Dentistry have discovered a key molecule that allows cancer stem cells to bypass the body's natural immune defenses, spurring the growth and spread of head and neck squamous cell cancers. Their study, conducted in mice, also demonstrates that inhibiting this molecule derails cancer progression and helps eliminate these stem cells.

Published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, the findings could help pave the way for more effective targeted treatments for this highly invasive type of cancer, which is characterized by frequent resistance to therapies, rapid metastasis and a high mortality rate.

Cancer stem cells, also known as tumor-initiating cells, are considered to be the original source of cancerous tissues -- the cells that give rise to all other cancer cells. Their ability to survive and proliferate in the early stages of cancer development, as well as during tumor growth and metastasis, suggests they have an intrinsic ability to evade detection by the body's immune surveillance system. The researchers set out to better understand how and why this happens.

When the immune system is functioning properly, the body's natural infection-fighting T cells help to identify and ward off carcinogenic cells, foreign viruses and other invaders. However, it is known that some cancer cells elude this immune response by means of protein molecules on their surface known as "checkpoints," which bind to similar molecules on the T cells, essentially nullifying the immune cells' cancer-killing capabilities.

To help rectify this, immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors can be administered; these drugs turn off the cancer cells' checkpoint receptors, allowing T cells to perform their normal job. In several types of cancer, including melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer, this approach has proven effective, decreasing the size of tumors and slowing their spread. Yet results for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas have been mixed, indicating that something else may be occurring that mutes the immune system's response.

To begin the study, the researchers tested a common checkpoint inhibitor that uses anti-PD1 antibodies on a well-defined mouse model of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The drug, they found, did very little to slow the spread of the cancer.

At the same time, they discovered that cancer stem cells in head and neck tumors had a notably elevated expression of the gene CD276, which encodes a protein molecule on the cell surface. They also found that CD276 expression was highest along the outer layers of tumors, suggesting that the CD276 molecule functions as a checkpoint that shields both the stem cells and cells in the interior of the tumor from the body's T cell response to the cancer.

Similar to the use of checkpoint inhibitors, the researchers next administered anti-CD276 antibodies to a mouse model of the disease to see if this treatment could turn off the checkpoint and inhibit the growth and spread of the cancer. After a month, they witnessed a significant decrease in the number of cancerous lesions and cancer stem cells.

"Not only did we see a reduction in cancer stem cells and tumors in our model when we introduced the CD276 antibodies, but we also noticed that the total number of tumors that metastasized to the lymph nodes was significantly reduced," said Dr. Cun-Yu Wang, the study's corresponding author and a professor of oral biology and medicine. "We were able to show that by blocking the gene CD276, we could effectively stop the growth of tumors derived from cancer stem cells."

Dr. Paul Krebsbach, dean of the UCLA School of Dentistry and a study co-author said, "These findings suggest that by focusing our attention on the CD276 gene and the immune response process, there is the potential for promising preventive therapeutic approaches against head and neck squamous cell carcinoma."

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Wang is the Dr. No-Hee Park Professor of Dentistry, a professor at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering and a member of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA.

Additional authors included Cheng Wang, Yang Li, Lingfei Jia, Jiong Li, Peng Deng and Wuchang Zhang, all of whom are part of the Laboratory of Molecular Signaling at the dentistry school and members of the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Broad Stem Cell Research Center. Dr. Paul Krebsbach and Jin koo Kim are both from the UCLA School of Dentistry.

A hot topic symposia session during thePediatric Academic Societies (PAS) 2021 Virtual Meeting will provide a forum for policy and physician experts to predict major child health legislative and policy changes which will occur over the next four years.

The outcome of the presidential election has significant impact on the child health policy agenda. The goal of the session is to prepare academic pediatricians so they can be ideally positioned to promote or impede specific policies which are not evidenced-based to improve child health.

"The subject matter ...

The emergence and spread of new forms of resistance remains a concern that urgently demand new antibiotics. Transcription is a vital process in bacterial cell, where genetic information in DNA is transcribed to RNA for the translation of proteins that perform cellular function. Hence, transcription serves as a promising target to develop new antibiotics because inhibition the transcription process should effectively kill the bacteria. Bacterial RNA Polymerase, the core enzyme for transcription, must load the DNA and separate the double-stranded DNA to single stranded DNA to read the genetic information to initiate transcription. This process is also called DNA melting and is facilitated ...

ORLANDO, May 5, 2021 - New research indicates that the legendary Sargasso Sea, which includes part of the Bermuda Triangle and has long featured in fiction as a place where ships go derelict, may actually be an important nursery habitat for young sea turtles.

In a study led by a University of Central Florida researcher and published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, researchers presented evidence of baby green sea turtles arriving at the Sargasso Sea after entering the ocean off the east coast of Florida.

The study was the first time that green sea turtles have been tracked during their early "lost years," which is defined ...

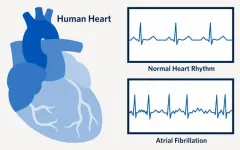

A UBC Okanagan researcher is urging people to learn and then heed the symptoms of Atrial Fibrillation (AF). Especially women.

Dr. Ryan Wilson, a post-doctoral fellow in the School of Nursing, says AF is the most commonly diagnosed arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) in the world. Despite that, he says many people do not understand the pre-diagnosis symptoms and tend to ignore them. In fact, 77 per cent of the women in his most recent study had experienced symptoms for more than a year before receiving a diagnosis.

While working in a hospital emergency department (ED), Dr. Wilson noted that many patients came in with AF symptoms that included, but were not limited to, shortness of breath, feeling of butterflies (fluttering) in the chest, dizziness or general fatigue. Many women ...

Seeing through smog and fog. Mapping out a person's blood vessels while monitoring heart rate at the same time--without touching the person's skin. Seeing through silicon wafers to inspect the quality and composition of electronic boards. These are just some of the capabilities of a new infrared imager developed by a team of researchers led by electrical engineers at the University of California San Diego.

The imager detects a part of the infrared spectrum called shortwave infrared light (wavelengths from 1000 to 1400 nanometers), which is right outside of the visible spectrum (400 to 700 nanometers). Shortwave infrared imaging is not to be confused with thermal imaging, which detects much longer infrared wavelengths ...

A new Tel Aviv University study has revealed, for the first time, that bats know the speed of sound from birth. In order to prove this, the researchers raised bats from the time of their birth in a helium-enriched environment in which the speed of sound is higher than normal. They found that unlike humans, who map the world in units of distance, bats map the world in units of time. What this means is that the bat perceives an insect as being at a distance of nine milliseconds, and not one and a half meters, as was thought until now.

The Study was published in PNAS.

In order to determine ...

PULLMAN, Wash. -- A count of the Western Monarch butterfly population last winter saw a staggering drop in numbers, but there are hopeful signs the beautiful pollinators are adapting to a changing climate and ecology.

The population, counted by citizen scientists at Monarch overwintering locations in southern California, dropped from around 300,000 three years ago to just 1,914 in 2020, leading to an increasing fear of extinction. However, last winter large populations of monarchs were found breeding in the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas. Prior to last winter, it was unusual to find winter breeding by monarchs ...

The idea of deriving health benefits from live microorganisms is well known, but some non-living microorganisms, too, can have beneficial health effects. Yet even with an increasing number of scientific papers published on non-viable microbes for health, the category is not well defined and different terms are used in different contexts.

Now, a group of international experts has clarified this concept in a recently END ...

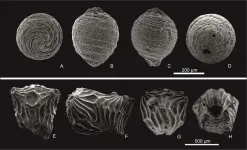

A study published in Cretaceous Research expands the paleontological richness of continental fossils of the Lower Cretaceous with the discovery of a new water plant (charophytes), the species Mesochara dobrogeica. The study also identifies a new variety of carophytes from the Clavator genus (in particular, Clavator ampullaceus var. latibracteatus) and reveals a set of paleobiographical data from the Cretaceous much richer than other continental records such as dinosaurs'.

Among the authors of the study are Josep Sanjuan, Alba Vicente, Jordi Pérez-Cano and Carles Martín-Closas, members of the Faculty of Earth Sciences and the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRBio) of the University of Barcelona, in collaboration with the expert Marius Stoica, ...

Ishikawa, Japan - Inside our cells, and those of the most well-known lifeforms, exist a variety of complex compounds known as "molecular motors." These biological machines are essential for various types of movement in living systems, from the microscopic rearrangement or transport of proteins within a single cell to the macroscopic contraction of muscle tissues. At the crossroads between robotics and nanotechnology, a goal that is highly sought after is finding ways to leverage the action of these tiny molecular motors to perform more sizeable tasks in a controllable manner. However, achieving this goal will certainly be challenging. "So far, even though researchers ...