Tracking down the tiniest of forces: How T cells detect invaders

T cells use their antigen receptors like sticky fingers -- a team from TU Wien and MedUni Vienna was able to observe them doing so

2021-05-05

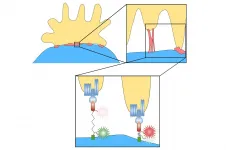

(Press-News.org) T-cells play a central role in our immune system: by means of their so-called T-cell receptors (TCR) they make out dangerous invaders or cancer cells in the body and then trigger an immune reaction. On a molecular level, this recognition process is still not sufficiently understood.

Intriguing observations have now been made by an interdisciplinary Viennese team of immunologists, biochemists and biophysicists. In a joint project funded by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund and the FWF, they investigated which mechanical processes take place when an antigen is recognized: As T cells move their TCRs pull on the antigen with a tiny force - about five pico-newtons (5 x 10-12 or 0.0000000005 newtons). This is not only sufficient to break the bonds between the TCRs and the antigen, it also helps T cells to find out whether they are interacting indeed with the antigen they are looking for. These results have now been published in the scientific journal "Nature Communications".

Tailor-made for a specific antigen

"Each T cell recognizes one specific antigen particularly well," explains Johannes Huppa, biochemist and immunology professor at MedUni Vienna.

"To do so, it features around 100,000 TCRs of the same kind on its surface."

When viruses attack our body, infected cells present various fragments of viral proteins on their surface. T cells examine such cells for the presence of such antigens. "This works according to the lock-and-key principle," explains Johannes Huppa. "For each antigen, the body must produce T cells with matching TCRs. Put simply, each T-cell recognizes only one specific antigen to then subsequently trigger an immune response."

That particular antigen, or more precisely, any antigenic protein fragment presented that exactly matches the T cell's TCR, can form a somewhat stable bond. The question that needs to be answered by the T cell is: how stable is the binding between antigen and receptor?

Like a finger on the sticky surface

"Let's say we wish to find out whether a surface is sticky - we then test how stable the bond is between the surface and our finger," says Gerhard Schütz, Professor of Biophysics at TU Wien. "We touch the surface and pull the finger away until it comes off. That's a good strategy because this pull-away behavior quickly and easily provides us information about the attractive force between the finger and the surface."

In principle, T-cells do exactly the same. T cells are not static, they deform continuously and their cell membrane is in constant motion. When a TCR binds to an antigen, the cell exerts a steadily increasing pulling force until the binding eventually breaks. This can provide information about whether it is the antigen that the cell is looking for.

A nano-spring for force measurement

"This process can actually be measured, even at the level of individual molecules," says Dr. Janett Göhring, who was active as coordinator and first author of the study at both MedUni Vienna and TU Vienna. "A special protein was used for this, which behaves almost like a perfect nano-spring, explain the two other first authors Florian Kellner and Dr. Lukas Schrangl from MedUni Vienna and TU Vienna respectively: "The more traction is exerted on the protein, the longer it becomes. With special fluorescent marker molecules, you can measure how much the length of the protein has changed, and that provides information about the forces that occur". In this way, the group was able to show that T cells typically exert a force of up to 5 pico-newtons - a tiny force that can nevertheless separate the receptor from the antigen. By comparison, one would have to pull on more than 100 million such springs simultaneously to feel stickiness with a finger.

"Understanding the behavior of T cells at the molecular level would be a huge leap forward for medicine. We are still leagues away from that goal," says Johannes Huppa. "But", adds Gerhard Schütz, "we were able to show that not only chemical but also mechanical effects play a role. They have to be considered together."

INFORMATION:

Original publication:

J. Göhring et al., Temporal analysis of T-cell receptor-imposed forces via quantitative single molecule FRET measurements, Nature Communications 12, 2502 (2021)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-22775-z

Contact:

Prof. Gerhard Schütz

Institut für Angewandte Physik

Technische Universität Wien

+43 1 58801 13480

gerhard.schuetz@tuwien.ac.at

Assoz. Prof. Johannes Huppa

Institut für Hygiene und Angewandte Immunologie

Medizinische Universität Wien

+43 1 40160 33004

johannes.huppa@meduniwien.ac.at

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-05

Larger bumblebees are more likely to go out foraging in the low light of dawn, new research shows.

University of Exeter scientists used RFID - similar technology to contactless card payments - to monitor when bumblebees of different sizes left and returned to their nest.

The biggest bees, and some of the most experienced foragers (measured by number of trips out), were the most likely to leave in low light.

Bumblebee vision is poor in low light, so flying at dawn or dusk raises the risk of getting lost or being eaten by a predator.

However, the bees benefit from extra foraging time and fewer competitors for pollen in the early morning.

"Larger bumblebees have bigger eyes than their smaller-sized nest mates and many other bees, and can therefore see better in dim light," said lead author ...

2021-05-05

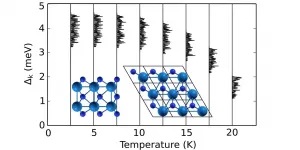

Superconductivity in two-dimensional (2D) systems has attracted much attention in recent years, both because of its relevance to our understanding of fundamental physics and because of potential technological applications in nanoscale devices such as quantum interferometers, superconducting transistors and superconducting qubits.

The critical temperature (Tc), or the temperature under which a material acts as a superconductor, is an essential concern. For most materials, it is between absolute zero and 10 Kelvin, that is, between -273 Celsius and -263 Celsius, too cold to be of any practical use. Focus has then been on finding materials with a higher Tc.

While researchers have discovered materials ...

2021-05-05

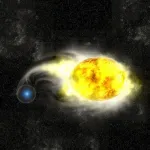

A curiously yellow pre-supernova star has caused astrophysicists to re-evaluate what's possible at the deaths of our Universe's most massive stars. The team describe the peculiar star and its resulting supernova in a new study published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

At the end of their lives, cool, yellow stars are typically shrouded in hydrogen, which conceals the star's hot, blue interior. But this yellow star, located 35 million light years from Earth in the Virgo galaxy cluster, was mysteriously lacking this crucial hydrogen layer at the time of its explosion.

"We haven't seen this scenario before," said Charles Kilpatrick, postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern ...

2021-05-05

How can a highly effective drug be transported to the precise location in the body where it is needed? In the journal Angewandte Chemie, chemists at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (HHU) together with colleagues in Aachen present a solution using a molecular cage that opens through ultrasonification.

Supramolecular chemistry involves the organization of molecules into larger, higher-order structures. When suitable building blocks are chosen, these systems 'self-assemble' from their individual components.

Certain supramolecular compounds are well suited for 'host-guest chemistry'. In such cases, a host structure encloses a guest molecule and can shield, protect and transport it away from its environment. This is a specialist field of Dr. Bernd M. Schmidt and ...

2021-05-05

The United States-Mexico border traverses through large expanses of unspoiled land in North America, including a newly discovered worldwide hotspot of bee diversity. Concentrated in 16 km2 of protected Chihuahuan Desert are more than 470 bee species, a remarkable 14% of the known United States bee fauna.

This globally unmatched concentration of bee species is reported by Dr. Robert Minckley of the University of Rochester and William Radke of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service in the open-access, peer-reviewed Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

Scientists studying native U.S. bees have long recognized that the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts of North America, home to species with interesting life histories, have high bee biodiversity. Exactly how many species ...

2021-05-05

Sanaria® PfSPZ-CVac" is a live vaccine consisting of infectious Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) malaria parasites that are injected into the subject at the same time as they receive an antimalarial drug. The parasites quickly enter the liver where they develop and multiply for 6 days, and then emerge into the blood As soon as the parasites leave the liver, the drug kills them immediately. Thus, the immune system of the vaccinated subject is primed against many parasite proteins and becomes highly effective at killing malaria parasites in the liver to block infection and prevent disease.

"With this study, we have reached a new important milestone in the development of an effective malaria vaccine. With only three immunizations over four weeks, we achieved very good protection ...

2021-05-05

Daniel Redhead, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and Chris von Rueden, from the University of Richmond, published a new study that describes coalition formation among men in Tsimané Amerindians living in Amazonian Bolivia, over a period of eight years. In two Tsimané communities, the authors describe the inter-personal conflicts that tend to arise between men, and the individual attributes and existing relationships that predict the coalitional support men receive in the event of conflicts.

Conflicts that arise between men concern disputes over access to forest for slash-and-burn horticulture, as well as accusations of theft, laziness, negligence, ...

2021-05-05

In about a quarter of patients with hereditary diseases, the cause of the disease remains unclear even after extensive genetic testing. One reason is that we still do not know enough about the function of many genes. Of the 30,000 known genes, just a little more than 4,000 have been found to be associated with hereditary diseases.

At the Department of Clinical Genetics of the University of Tartu Institute of Clinical Medicine, under the leadership of Professor Katrin Õunap, patients with hereditary diseases of unclear cause have been studied in various research projects since 2016. In collaboration with the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, these patients have undergone extensive genome-wide sequencing analyses at the level of the exome (the sequence of all genes), ...

2021-05-05

Knowing what species live in which parts of the world is critical to many fields of study, such as conservation biology and environmental monitoring. This is also how we can identify present or potential invasive and non-native pest species. Furthermore, summarizing what species are known to inhabit a given area is essential for the discovery of new species that have not yet been known to science.

For less well-studied groups and regions, distributional species checklists are often not available. Therefore, a series of such checklists is being published in the open-access, peer-reviewed Journal of Hymenoptera Research, in order ...

2021-05-05

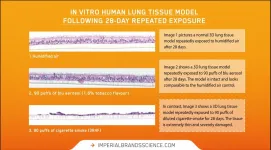

5 May 2021, Bristol - In one of the most advanced applications of in-vitro 3D human lung models in vape research to date, a new peer-reviewed Imperial Brands study shows that, unlike combustible cigarette smoke, blu aerosol had little to no impact on numerous toxicological endpoints under the conditions of test using laboratory models.

Published in the journal Current Research in Toxicology, the experiments compared the toxicological responses of an in vitro 3D lung model (MucilAir™ from Epithelix) after repeated exposure to undiluted whole blu aerosol (1.6% tobacco flavour) or diluted whole cigarette smoke (3R4F Kentucky Reference) over a 28-day period.

After repeatedly exposing the model to ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Tracking down the tiniest of forces: How T cells detect invaders

T cells use their antigen receptors like sticky fingers -- a team from TU Wien and MedUni Vienna was able to observe them doing so