Fundamental regulation mechanism of proteins discovered

A research team led by Göttingen University find novel switch in proteins with wide-ranging implications for medical treatments

2021-05-05

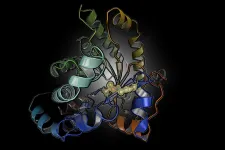

(Press-News.org) Proteins perform a vast array of functions in the cell of every living organism with critical roles in almost every biological process. Not only do they run our metabolism, manage cellular signaling and are in charge of energy production, as antibodies they are also the frontline workers of our immune system fighting human pathogens like the coronavirus. In view of these important duties, it is not surprising that the activity of proteins is tightly controlled. There are numerous chemical switches that control the structure and, therefore, the function of proteins in response to changing environmental conditions and stress. The biochemical structures and modes of operation of these switches were thought to be well understood. So a team of researchers at the University of Göttingen were surprised to discover a completely novel, but until now overlooked, on/off switch that seems to be a ubiquitous regulatory element in proteins in all domains of life. The results were published in Nature.

The researchers investigated a protein from the human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae that causes gonorrhea, a bacterial infection with over 100 million cases worldwide. This disease is typically treated with antibiotics but increasing rates of antibiotic resistance pose a serious threat. In order to identify new treatments, they studied the structure and mechanism of a protein that is a key player in carbon metabolism of the pathogen. Surprisingly, the protein can be switched on and off by oxidation and reduction (known as a "redox switch). The scientists suspected this was caused by a common and well-established "disulfide switch" formed between two cysteine amino acids. When they deciphered the X-ray structures of the protein in the "on" and "off" state at the DESY particle accelerator in Hamburg, Germany, they were hit by an even bigger surprise. The chemical nature of the switch was completely unknown: it is formed between a lysine and a cysteine amino acid with a bridging oxygen atom.

"I couldn't believe my eyes," says Professor Kai Tittmann, who led the study, when he remembers seeing the structure of the novel switch for the first time. "We thought initially that this must have formed artificially as a by-product of the experimental process as this chemical entity was unknown." However, numerous repetitions of the experiments always gave the same result and an analysis of the protein structure database further disclosed that there are many other proteins that very likely possess this switch, which apparently escaped earlier detection as the resolution of the protein structure analysis was insufficient to detect it for certain. The researchers admit that good fortune was on their side because the crystals they measured allowed the protein structure to be determined at extremely high resolution, meaning the novel switch couldn't be missed. "The extensive screening for high-quality protein crystals has really paid off, I couldn't be happier," says Marie Wensien, first author of the paper.

The researchers believe the discovery of the novel protein switch will impact the life sciences in numerous ways, for instance in the field of protein design. It will also open new avenues in medical applications and drug design. Many human proteins with established roles in severe diseases are known to be redox-controlled and the newly discovered switch is likely to play a central role in regulating their biological function as well.

INFORMATION:

Researchers from the Göttingen Center for Molecular Biosciences (GZMB), the Faculty of Chemistry of the University of Göttingen, the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry and the Hannover Medical School contributed to the study.

Original publication: Marie Wensien et al. A lysine-cysteine redox switch with an NOS bridge regulates enzyme function. Nature 2021. DoI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03513-3

Contact:

Professor Kai Tittmann

University of Göttingen

Department of Molecular Enzymology

Julia-Lermontowa-Weg 3, 37077 Göttingen

Tel: +49 (0)551-39177811

Email: ktittma@gwdg.de

http://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/sh/198266.html

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-05

Philadelphia, May 5, 2021--When Luke Terrio was about seven months old, his mother began to realize something was off. He had constant ear infections, developed red spots on his face, and was tired all the time. His development stagnated, and the antibiotics given to treat his frequent infections stopped working. His primary care doctor at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) ordered a series of blood tests and quickly realized something was wrong: Luke had no antibodies.

At first, the CHOP specialists treating Luke thought he might have X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), a rare immunodeficiency syndrome seen in children. However, as the CHOP research team continued investigating Luke's case, they realized Luke's condition was unlike any disease described ...

2021-05-05

Pesticides have been used in European agriculture for more than 70 years, so monitoring their presence, levels and their effects in European soils quality and services is needed to establish protocols for the use and the approval of new plant protection products.

In an attempt to deal with this issue, a team led by the prof. Dr. Violette Geissen from Wageningen University (Netherlands) have analysed 340 soil samples originating from three European countries to compare the contentdistribution of pesticide cocktails in soils under organic farming practices and soils under conventional practices. This study was a combined effort of 3 EC funded projects addressing soil

quality: RECARE (http://www.recare-project.eu/), iSQAPER (http://www.isqaper-project.eu) ...

2021-05-05

T-cells play a central role in our immune system: by means of their so-called T-cell receptors (TCR) they make out dangerous invaders or cancer cells in the body and then trigger an immune reaction. On a molecular level, this recognition process is still not sufficiently understood.

Intriguing observations have now been made by an interdisciplinary Viennese team of immunologists, biochemists and biophysicists. In a joint project funded by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund and the FWF, they investigated which mechanical processes take place when an antigen is recognized: ...

2021-05-05

Larger bumblebees are more likely to go out foraging in the low light of dawn, new research shows.

University of Exeter scientists used RFID - similar technology to contactless card payments - to monitor when bumblebees of different sizes left and returned to their nest.

The biggest bees, and some of the most experienced foragers (measured by number of trips out), were the most likely to leave in low light.

Bumblebee vision is poor in low light, so flying at dawn or dusk raises the risk of getting lost or being eaten by a predator.

However, the bees benefit from extra foraging time and fewer competitors for pollen in the early morning.

"Larger bumblebees have bigger eyes than their smaller-sized nest mates and many other bees, and can therefore see better in dim light," said lead author ...

2021-05-05

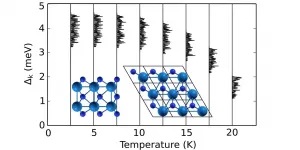

Superconductivity in two-dimensional (2D) systems has attracted much attention in recent years, both because of its relevance to our understanding of fundamental physics and because of potential technological applications in nanoscale devices such as quantum interferometers, superconducting transistors and superconducting qubits.

The critical temperature (Tc), or the temperature under which a material acts as a superconductor, is an essential concern. For most materials, it is between absolute zero and 10 Kelvin, that is, between -273 Celsius and -263 Celsius, too cold to be of any practical use. Focus has then been on finding materials with a higher Tc.

While researchers have discovered materials ...

2021-05-05

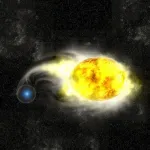

A curiously yellow pre-supernova star has caused astrophysicists to re-evaluate what's possible at the deaths of our Universe's most massive stars. The team describe the peculiar star and its resulting supernova in a new study published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

At the end of their lives, cool, yellow stars are typically shrouded in hydrogen, which conceals the star's hot, blue interior. But this yellow star, located 35 million light years from Earth in the Virgo galaxy cluster, was mysteriously lacking this crucial hydrogen layer at the time of its explosion.

"We haven't seen this scenario before," said Charles Kilpatrick, postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern ...

2021-05-05

How can a highly effective drug be transported to the precise location in the body where it is needed? In the journal Angewandte Chemie, chemists at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf (HHU) together with colleagues in Aachen present a solution using a molecular cage that opens through ultrasonification.

Supramolecular chemistry involves the organization of molecules into larger, higher-order structures. When suitable building blocks are chosen, these systems 'self-assemble' from their individual components.

Certain supramolecular compounds are well suited for 'host-guest chemistry'. In such cases, a host structure encloses a guest molecule and can shield, protect and transport it away from its environment. This is a specialist field of Dr. Bernd M. Schmidt and ...

2021-05-05

The United States-Mexico border traverses through large expanses of unspoiled land in North America, including a newly discovered worldwide hotspot of bee diversity. Concentrated in 16 km2 of protected Chihuahuan Desert are more than 470 bee species, a remarkable 14% of the known United States bee fauna.

This globally unmatched concentration of bee species is reported by Dr. Robert Minckley of the University of Rochester and William Radke of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service in the open-access, peer-reviewed Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

Scientists studying native U.S. bees have long recognized that the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts of North America, home to species with interesting life histories, have high bee biodiversity. Exactly how many species ...

2021-05-05

Sanaria® PfSPZ-CVac" is a live vaccine consisting of infectious Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) malaria parasites that are injected into the subject at the same time as they receive an antimalarial drug. The parasites quickly enter the liver where they develop and multiply for 6 days, and then emerge into the blood As soon as the parasites leave the liver, the drug kills them immediately. Thus, the immune system of the vaccinated subject is primed against many parasite proteins and becomes highly effective at killing malaria parasites in the liver to block infection and prevent disease.

"With this study, we have reached a new important milestone in the development of an effective malaria vaccine. With only three immunizations over four weeks, we achieved very good protection ...

2021-05-05

Daniel Redhead, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and Chris von Rueden, from the University of Richmond, published a new study that describes coalition formation among men in Tsimané Amerindians living in Amazonian Bolivia, over a period of eight years. In two Tsimané communities, the authors describe the inter-personal conflicts that tend to arise between men, and the individual attributes and existing relationships that predict the coalitional support men receive in the event of conflicts.

Conflicts that arise between men concern disputes over access to forest for slash-and-burn horticulture, as well as accusations of theft, laziness, negligence, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Fundamental regulation mechanism of proteins discovered

A research team led by Göttingen University find novel switch in proteins with wide-ranging implications for medical treatments