(Press-News.org) Besides being underweight, babies born to women whose diet lacked sufficient protein during pregnancy tend to have kidney problems resulting from alterations that occurred while their organs were forming during the embryonic stage of their development.

In a study published in PLOS ONE, researchers affiliated with the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, discovered the cause of the problem at the molecular level and its link to epigenetic phenomena (changes in gene expression due to environmental factors such as stress, exposure to toxins or malnutrition, among others).

According to the authors, between 10% and 13% of the world population suffer from chronic kidney disease, a gradual irreversible loss of renal function that is associated with high blood pressure and cardiovascular disorder.

The study, conducted at the Obesity and Comorbidities Research Center (OCRC), resulted from PhD research by first author Letícia de Barros Sene with a fellowship from FAPESP.

OCRC is a Research, Innovation and Dissemination Center (RIDC) funded by FAPESP.

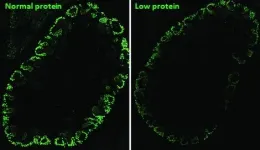

In the article, the researchers describe the molecular pathways involved in the proliferation and differentiation of embryonic and fetal kidney cells. They obtained this knowledge by sequencing microRNAs (often called miRNAs) from the offspring of rats fed a low-protein diet while gestating. MirRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression.

“We know low-protein intake during pregnancy tends to lead to a 28% decrease in the number of the offspring’s nephrons, the structures that filter blood in the kidneys. The resulting overloading of nephrons has several consequences. In the case of rats, pups become hypertensive only ten weeks after birth, when they are still considered young,” Patrícia Aline Boer, a member of the OCRC team and last author of the article, told Agência FAPESP. A healthy kidney has about a million nephrons.

Fetal programming

There has been a great deal of research in recent decades on the links between maternal health during pregnancy and child development, especially focusing on a field known as developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD).

“In humans, these links were first observed after World War Two as a result of what’s known as the ‘Dutch famine’ [Hongerwinter], when the Nazis blocked food supplies to the Netherlands. Scientific studies showed that babies born to women who starved while pregnant in this period were underweight and developed high blood pressure, alterations in response to stress, heart problems, propensity to diabetes, and increased insulin resistance,” said Boer, who is president of DOHaD Brazil.

Since then, this epigenetic phenomenon has been studied in greater depth using animal experiment models. To understand at the molecular level what triggered the reduction in the number of nephrons, the OCRC researchers analyzed expression of miRNAs and target genes in fetal kidneys (metanephros) of rats at 17 days of gestation.

“We know the drop in the number of nephrons isn’t a genetic but an epigenetic effect,” Boer said. “It’s caused by something in the environment. In this case, gene expression is altered by the stress of hypoproteinemia. The DNA sequence doesn’t change. The expression of some genes in the offspring is altered, and the alteration can be heritable – it can be transmitted to future generations. We studied mirRNAs because they’re very important to genetic expression and alterations not associated with changes in DNA.”

Compared analysis between rats fed a regular protein diet (17% of daily calorie intake) and a second group fed a low-protein diet (6%) during pregnancy revealed alterations in 44 miRNAs – seven of which in genes associated with the proliferation and differentiation of cells essential to nephron development, researchers found. Genetic sequencing, immunohistochemistry and morphological analysis demonstrated that maternal protein restriction changed the expression of miRNAs and proteins involved in renal development as early as the 17th day of gestation.

“Previous research showed a 28% reduction in nephrogenesis, and in our study, there was a 28% decrease in the cells that give rise to nephrons. The proportion was the same, which means there must be some kind of signaling during the embryonic period that the organ has to adapt to a low-protein intake,” Boer said.

Other examples of fetal adaptation to malnutrition leading to alterations in organ development can be found in nature, Boer explained. “In our study, we observed that stem cells [which will become nephrons] differentiate very rapidly and that there was more differentiation and less proliferation of the cells that form nephrons,” she said.

The article “Impact of gestational low-protein intake on embryonic kidney microRNA expression and in nephron progenitor cells of the male fetus” (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246289) by Letícia de Barros Sene, Wellerson Rodrigo Scarano, Adriana Zapparoli, José Antônio Rocha Gontijo and Patrícia Aline Boer is at: journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0246289.

Study shows how low-protein intake during pregnancy can cause renal problems in offspring

In an article published in PLOS ONE, scientists at a FAPESP-supported research center describe the impact of hypoproteinemia on the expression of microRNAs associated with kidney development in rat embryos.

2021-05-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Long-acting injectable medicine as potential route to COVID-19 therapy

2021-05-05

Researchers from the University of Liverpool have shown the potential of repurposing an existing and cheap drug into a long-acting injectable therapy that could be used to treat Covid-19.

In a paper published in the journal Nanoscale, researchers from the University's Centre of Excellence for Long-acting Therapeutics (CELT) demonstrate the nanoparticle formulation of niclosamide, a highly insoluble drug compound, as a scalable long-acting injectable antiviral candidate.

The team started repurposing and reformulating identified drug compounds with the potential for COVID-19 therapy candidates within weeks of the first lockdown. Niclosamide is just one of the drug compounds identified and has been shown to be highly effective against SARS-CoV-2 in a number of laboratory studies.

Using ...

Johns Hopkins scientists model Saturn's interior

2021-05-05

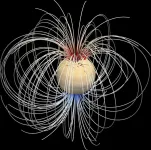

New Johns Hopkins University simulations offer an intriguing look into Saturn's interior, suggesting that a thick layer of helium rain influences the planet's magnetic field.

The models, published this week in AGU Advances, also indicate that Saturn's interior may feature higher temperatures at the equatorial region, with lower temperatures at the high latitudes at the top of the helium rain layer.

It is notoriously difficult to study the interior structures of large gaseous planets, and the findings advance the effort to map Saturn's hidden regions.

"By ...

Now available with a negative charge too

2021-05-05

The incorporation of boron into polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon systems leads to interesting chromophoric and fluorescing materials for optoelectronics, including organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDS) and field-effect transistors, as well as polymer-based sensors. In the journal Angewandte Chemie, a research team has now introduced a new anionic organoborane compound. Synthesis of the borafluorene succeeded through the use of carbenes.

Borafluorene is a particularly interesting boron-containing building block. It is a system of three carbon rings joined at the edges: two six-membered and one central five-membered ring, whose free tip is the boron atom. While neutral, radical, and cationic (positively ...

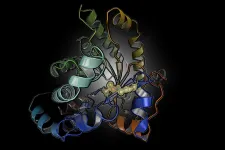

Fundamental regulation mechanism of proteins discovered

2021-05-05

Proteins perform a vast array of functions in the cell of every living organism with critical roles in almost every biological process. Not only do they run our metabolism, manage cellular signaling and are in charge of energy production, as antibodies they are also the frontline workers of our immune system fighting human pathogens like the coronavirus. In view of these important duties, it is not surprising that the activity of proteins is tightly controlled. There are numerous chemical switches that control the structure and, therefore, the function of proteins in response to changing environmental conditions and stress. ...

CHOP researchers discover new disease that prevents formation of antibodies

2021-05-05

Philadelphia, May 5, 2021--When Luke Terrio was about seven months old, his mother began to realize something was off. He had constant ear infections, developed red spots on his face, and was tired all the time. His development stagnated, and the antibiotics given to treat his frequent infections stopped working. His primary care doctor at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) ordered a series of blood tests and quickly realized something was wrong: Luke had no antibodies.

At first, the CHOP specialists treating Luke thought he might have X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), a rare immunodeficiency syndrome seen in children. However, as the CHOP research team continued investigating Luke's case, they realized Luke's condition was unlike any disease described ...

Revealing the impact of 70 years of pesticide use on European soils

2021-05-05

Pesticides have been used in European agriculture for more than 70 years, so monitoring their presence, levels and their effects in European soils quality and services is needed to establish protocols for the use and the approval of new plant protection products.

In an attempt to deal with this issue, a team led by the prof. Dr. Violette Geissen from Wageningen University (Netherlands) have analysed 340 soil samples originating from three European countries to compare the contentdistribution of pesticide cocktails in soils under organic farming practices and soils under conventional practices. This study was a combined effort of 3 EC funded projects addressing soil

quality: RECARE (http://www.recare-project.eu/), iSQAPER (http://www.isqaper-project.eu) ...

Tracking down the tiniest of forces: How T cells detect invaders

2021-05-05

T-cells play a central role in our immune system: by means of their so-called T-cell receptors (TCR) they make out dangerous invaders or cancer cells in the body and then trigger an immune reaction. On a molecular level, this recognition process is still not sufficiently understood.

Intriguing observations have now been made by an interdisciplinary Viennese team of immunologists, biochemists and biophysicists. In a joint project funded by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund and the FWF, they investigated which mechanical processes take place when an antigen is recognized: ...

Large bumblebees start work earlier

2021-05-05

Larger bumblebees are more likely to go out foraging in the low light of dawn, new research shows.

University of Exeter scientists used RFID - similar technology to contactless card payments - to monitor when bumblebees of different sizes left and returned to their nest.

The biggest bees, and some of the most experienced foragers (measured by number of trips out), were the most likely to leave in low light.

Bumblebee vision is poor in low light, so flying at dawn or dusk raises the risk of getting lost or being eaten by a predator.

However, the bees benefit from extra foraging time and fewer competitors for pollen in the early morning.

"Larger bumblebees have bigger eyes than their smaller-sized nest mates and many other bees, and can therefore see better in dim light," said lead author ...

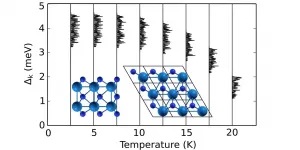

Superconductivity, high critical temperature found in 2D semimetal W2N3

2021-05-05

Superconductivity in two-dimensional (2D) systems has attracted much attention in recent years, both because of its relevance to our understanding of fundamental physics and because of potential technological applications in nanoscale devices such as quantum interferometers, superconducting transistors and superconducting qubits.

The critical temperature (Tc), or the temperature under which a material acts as a superconductor, is an essential concern. For most materials, it is between absolute zero and 10 Kelvin, that is, between -273 Celsius and -263 Celsius, too cold to be of any practical use. Focus has then been on finding materials with a higher Tc.

While researchers have discovered materials ...

Mysterious hydrogen-free supernova sheds light on stars' violent death throes

2021-05-05

A curiously yellow pre-supernova star has caused astrophysicists to re-evaluate what's possible at the deaths of our Universe's most massive stars. The team describe the peculiar star and its resulting supernova in a new study published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

At the end of their lives, cool, yellow stars are typically shrouded in hydrogen, which conceals the star's hot, blue interior. But this yellow star, located 35 million light years from Earth in the Virgo galaxy cluster, was mysteriously lacking this crucial hydrogen layer at the time of its explosion.

"We haven't seen this scenario before," said Charles Kilpatrick, postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

[Press-News.org] Study shows how low-protein intake during pregnancy can cause renal problems in offspringIn an article published in PLOS ONE, scientists at a FAPESP-supported research center describe the impact of hypoproteinemia on the expression of microRNAs associated with kidney development in rat embryos.