(Press-News.org) Early in human development, during the first trimester of gestation, a fetus may have XX or XY chromosomes that indicate its sex. Yet at this stage a mass of cells known as the bipotential gonad that ultimately develops into either ovaries or testes has yet to commit to its final destiny.

While researchers had studied the steps that go into the later stages of this process, little has been known about the precursors of the bipotential gonad. In a new study published in Cell Reports and co-led by Kotaro Sasaki of Penn's School of Veterinary Medicine, an international team lays out the detailed development of this key facet of sexual determination in two mammalian models.

"Using single-cell transcriptome data, we can get a lot of information about gene expression at each developmental stage," says Sasaki. "We can define what the default process is and how it might go awry in some cases. This has never been done in traditional developmental biology. Now we can understand development in molecular terms."

Disorders of sex development (DSD) occur when internal and external reproductive structures develop differently from what would be expected based on an individuals' genetics. For example someone with XY chromosomes might develop ovaries. These conditions often affect fertility and are associated with an increased risk of germ cell tumors.

"These disorders oftentimes create psychological and physical distress for patients," Sasaki says. "That's why understanding gonadal development is important."

To understand atypical development, Sasaki and colleagues in the current study sought to layout the steps of typical development, working with a mouse model and a monkey model.

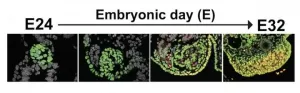

The researchers began by examining mouse embryos throughout embryonic development, using molecular markers to track the location of different proteins suspected to be involved in the formation of reproductive structures. They noticed that by day nine of a mouse's embryonic development, a structure called the posterior intermediate mesoderm (PIM) lit up brightly with the marker for a gene critical to the development of gonads, kidneys, and the hormone-producing adrenal glands, which are located adjacent to the kidneys.

Zeroing in on the PIM and its progeny cells, the team found that, by day 10.5, these also expressed a marker known to be associated with the bipotential gonad.

"People have previously studied the origin of the urogenital organs and the kidney and based on that believed that their origins were very close," Sasaki says. "So our hypothesis was that the PIM was the origin of the gonads as well as the kidneys."

To identify the origin of the gonad, they performed lineage tracing, in which scientists label cells in order to track their descendents, which indeed supported the connection between the PIM and the gonads.

To further confirm that the PIM played a similar role in an organism closer to humans in reproductive biology, the researchers made similar observations in embryos from cynomolgus monkeys. Though the developmental timing was different from the mouse, as was expected, the PIM again appeared to give rise to the bipotential gonad.

Digging even deeper into the molecular mechanism of the transition between the PIM and bipotential gonad, the researchers used a cutting-edge technique: single-cell sequencing analysis, whereby they can identify which genes are being turned on during each developmental stage.

Not only were they able to identify genes that were turned on--many of which had never before been associated with reproductive development--but they observed a transition state between the PIM and bipotential gonad, called the coelomic epithelium. Comparing the mice and monkey embryos, the researchers came up with a group of genes that were conserved, or shared between the species. "Some of these genes are already known to be important for the development of mouse and human ovaries and testes," Sasaki says, "and some have been implicated in the development of DSDs."

He notes that in roughly half of patients with DSDs, however, the genetic cause is unknown. "So this database we're assembling may now be used to predict some additional genes that are important in DSD and could be used for screening and diagnosis of DSDs, or even treatment and prevention."

The study also illuminated the relationship between the origin of the kidneys, adrenal glands, and gonads. "They all originate from the PIM, but the timing and positioning is different," Sasaki says.

The adrenal glands, he says, develop from the anterior portion of the PIM, or that section closer to the head and arise early, while the kidney arises later from the posterior portion of the PIM. The gonadal glands span the PIM, with some regions developing earlier and others later.

In future studies, Sasaki and colleagues would like to continue teasing out the details and stages of gonadal development. Sasaki's ultimate goal is to coax a patient's own stem cells to grow into reproductive organs in the lab.

"Some patients with DSDs don't have ovaries and testes, and some cancer patients undergo chemotherapy and completely lose their ovary function," Sasaki says. "If you could induce a stem cell to grow into an ovary in the lab, you could provide a replacement therapy for these patients, allowing them to regain normal hormone levels and even fertility. With a precise molecular map to the developing gonad in hand, we are now one step closer to the this goal."

INFORMATION:

Kotaro Sasaki is an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences in the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

Sasaki's coauthors on the study were Penn's Keren Cheng and Yasunari Seita; Kyoto University's Akiko Oguchi, Yasuhiro Murakawa, Ikuhiro Okamoto, Hiroshi Ohta, Yukihiro Yabuta, Takuya Yamamoto, and Mitinori Saitou; and Shiga University of Medical Science's Chizuru Iwatani and Hideaki Tsuchiya. Sasaki and Saitou were corresponding authors.

The study was supported by a JST-ERATO Grant (JPMJER1104), Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research from JSPS (17H06098), the Pythias Fund, and the Open Philanthropy Fund from Silicon Valley Community Foundation (2019-197906).

Although the fairy tale of the wicked stepmother is a tale as old as time, the effects of blending children with their new stepfamilies may not be as grim as once thought.

In fact, new research shows that stepparents are not at a disadvantage compared to their peers from single-parent households and actually experience better outcomes than their halfsiblings -- good news for the more than 113 million Americans that are part of a steprelationship.

Led by East Carolina University anthropologist Ryan Schacht and researchers from the University of Utah, the study, "Was Cinderella just a fairy tale? Survival differences between stepchildren and their half-siblings," is available in the May edition of the Philosophical Transactions ...

The European Alps is certainly one of the most scrutinized mountain range in the world, as it forms a true open-air laboratory showing how climate change affects biodiversity. Although many studies have independently demonstrated the impact of climate change in the Alps on either the seasonal activity (i.e. phenology) or the migration of plants and animals, no systematic analysis has been carried out on both consequences simultaneously. A European team of ecologists1, including Jonathan Lenoir, CNRS Researcher in the research unit Écologie et Dynamique des Systèmes Anthropisés (CNRS/University of Picardie Jules Verne), has just published a review that ...

Cells of all life forms are surrounded by a membrane that is made of phospholipids. One of these are the cardiolipins, which form a separate class due to their unique structure. When studying the enzyme that is responsible for producing cardiolipins in archaea (single-cell organisms that constitute a separate domain of life), biochemists at the University of Groningen made a surprising discovery. A single archaeal enzyme can produce a spectacular range of natural and non-natural cardiolipins, as well as other phospholipids. The results, which show potential for biotechnological applications, ...

Lessons Learned from India's Polio Vaccination Program Provide Valuable Insights for Future Mass Vaccination Initiatives.

Toronto - As India urgently scales up its vaccination campaign for the COVID-19 virus, a new study which examined the country's successful program to eliminate polio provides guidance on how this and future mass immunization campaigns can be successful, especially in vaccinating hard to reach groups.

The study, conducted by students and faculty with the Reach Alliance, a research initiative based at the University of Toronto's Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, says that medicine alone is insufficient for the elimination of disease.

The World Health Organization declared India polio-free in 2014. ...

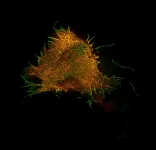

AMHERST, Mass. - A team of researchers at the Center for Bioactive Delivery at the University of Massachusetts Amherst's Institute for Applied Life Sciences has engineered a nanoparticle that has the potential to revolutionize disease treatment, including for cancer. This new research, which appears today in Angewandte Chemie, combines two different approaches to more precisely and effectively deliver treatment to the specific cells affected by cancer.

Two of the most promising new treatments involve delivery of cancer-fighting drugs via biologics or antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs). Each has its own advantages and limitations. Biologics, such as protein-based ...

May 6, 2021 -- A significant level of symptoms of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress may follow COVID-19 independent of any previous psychiatric diagnoses, according to new research by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health with colleagues at Universidade Municipal de São Caetano do Sul in Brazil. Exposure to increased symptomatic levels of COVID-19 may be associated with psychiatric symptoms after the acute phase of the disease. This is the largest study to evaluate depressive, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms in tandem among patients who had mild COVID-19 ...

Quantum computers or quantum sensors consist of materials that are completely different to their classic predecessors. These materials are faced with the challenge of combining contradicting properties that quantum technologies entail, as for example good accessibility of quantum bits with maximum shielding from environmental influences. In this regard, so-called two-dimensional materials, which only consist of a single layer of atoms, are particularly promising.

Researchers at the new Center for Applied Quantum Technologies and the 3rd Institute of Physics at the University of Stuttgart have now succeeded in identifying promising quantum bits in these materials. They were able to show that the quantum bits can be generated, read out and coherently controlled in a very ...

The Marburg virus, a relative of the Ebola virus, causes a serious, often-fatal hemorrhagic fever. Transmitted by the African fruit bat and by direct human-to-human contact, Marburg virus disease currently has no approved vaccine or antivirals to prevent or treat it.

A team of researchers is working to change that. In a new paper in the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, investigators from Penn's School of Veterinary Medicine, working together with scientists from the Fox Chase Chemical Diversity Center and the Texas Biomedical Research Institute, report encouraging results from tests of an experimental ...

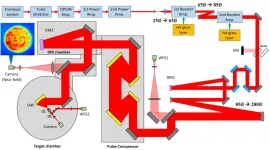

WASHINGTON -- Researchers have demonstrated a record-high laser pulse intensity of over 1023 W/cm2 using the petawatt laser at the Center for Relativistic Laser Science (CoReLS), Institute for Basic Science in the Republic of Korea. It took more than a decade to reach this laser intensity, which is ten times that reported by a team at the University of Michigan in 2004. These ultrahigh intensity light pulses will enable exploration of complex interactions between light and matter in ways not possible before.

The powerful laser can be used to examine phenomena believed to be responsible for ...

Recently, laser scientists at the Center for Relativistic Laser Science (CoReLS) within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) in South Korea realized the unprecedented laser intensity of 1023 W/cm2. This has been a milestone that has been pursued for almost two decades by many laser institutes around the world.

An ultrahigh intensity laser is an important research tool in several fields of science, including those which explore novel physical phenomena occurring under extreme physical conditions. Since the demonstration of the 1022 W/cm2 intensity laser by a team at the ...