(Press-News.org) The bulging, equator-belted midsection of Earth currently teems with a greater diversity of life than anywhere else -- a biodiversity that generally wanes when moving from the tropics to the mid-latitudes and the mid-latitudes to the poles.

As well-accepted as that gradient is, though, ecologists continue to grapple with the primary reasons for it. New research from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Yale University and Stanford University suggests that temperature can largely explain why the greatest variety of aquatic life resides in the tropics -- but also why it has not always and, amid record-fast global warming, soon may not again.

Published May 6 in the journal Current Biology, the study estimates that marine biodiversity tends to increase until the average surface temperature of the ocean reaches about 65 degrees Fahrenheit, beyond which that diversity slowly declines.

During intervals of Earth's history when the maximum surface temperature was lower than 80 degrees Fahrenheit, the greatest biodiversity was found around the equator, the study concluded. But when that maximum exceeded 80 degrees, marine biodiversity ebbed in the tropics, where those highest temperatures would have manifested, while peaking in waters at the mid-latitudes and the poles.

Marine life that could travel considerable distances likely migrated north or south from the tropics during periods of extreme heat, said co-author Will Gearty, a postdoctoral researcher of biological sciences at Nebraska. Stationary or slower-moving animals, such as sponges and sea stars, may have instead faced extinction.

"People have always theorized that the tropics are a cradle of diversity -- that it pops up and then is protected there," Gearty said. "There's also this idea that ... there's lots of migration toward the tropics, but not away from it. All of that centers around the idea that the highest diversity will always be in the tropics. And that's not what we see as we go back in time."

Gearty, Yale's Thomas Boag and Stanford's Richard Stockey went back about 145 million years, compiling estimated temperatures and fossil records of mollusks -- snails, clams, cephalopods and the like -- from 24 horizontal bands of Earth that were equal in surface area. The trio chose mollusk records for multiple reasons: They live (and lived) around the globe, in large enough numbers to accommodate statistical analyses, with hard enough shells to yield identifiable fossils, with enough variation that their diversity trends might generalize to fish, corals, crustaceans and an array of other marine animals.

That data allowed the team to derive the temperature-diversity relationship across 10 geologic intervals that covered most of the elapsed time from the Cretaceous period through the modern day.

"Temperature seems to account for a lot of the trend that we see in the fossil record," Gearty said. "There are certainly other factors, but this seems to be the first-order predictor of what's going on."

To investigate why temperature might be so influential and predictive, Stockey took the lead in developing a mathematical model. The model accounts for the fact that higher temperatures generally increase the amount of energy in an ecosystem, theoretically raising the ceiling on the biodiversity an ecosystem can sustain, at least to a point.

But it also factors in metabolism and the small matter of oxygen, which, by dissolving in water, makes aquatic life possible in the first place. Colder waters dissolve more oxygen, meaning that elevated temperatures naturally reduce the amount available to marine life and, by extension, potentially limit the biodiversity an ecosystem can support. Higher temperatures also raise the metabolic demands of organisms, increasing the minimum oxygen needed to sustain active marine animals.

"That means you require more oxygen in warmer waters," Gearty said. "And if the amount of oxygen available is not satisfying that increase in metabolism, you won't survive in that environment. So, to survive, you'll need to move to another environment where the temperature is lower."

The team applied its model to numerous marine species with varying metabolisms. As expected, metabolism influenced how the population of a given species would respond to a rise in temperature, along with the temperature threshold beyond which that population would decline. When the researchers averaged the effects of metabolism and oxygen availability across those species, they discovered that the resulting temperature-diversity relationship resembled -- and, in doing so, supported -- the one they derived from the fossil record.

"It shows a similar trend of this (biodiversity) increase and then decrease," Gearty said. "After many a day at the whiteboard just trying to figure out how to make it work, it all just came together very nicely at the end -- you know, a nice little bow on top."

Collectively, the study indicates that human-driven global warming could hit the inhabitants of tropical waters especially hard. The average surface temperature of tropical waters could jump by as many as 6 degrees Fahrenheit by the year 2300, according to one projection. And according to the fossil records analyzed for the study, similar temperature increases during the past 145 million years have sometimes permanently driven mollusk species from tropical waters. There are worrying signs that the expected trend is already underway, Gearty said.

Though the team had difficulty narrowing down the projected magnitude of the decline in biodiversity, Gearty said the worst-case projection called for the tropics losing up to 50% of their marine species by 2300. Some of the loss will take the form of migration. Yet the warming could spell doom for, say, corals and the thousands of marine species that they support, he said, as seen in the oft-fatal bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia.

"This (biodiversity loss) is already happening, and it will only keep happening unless we do something," Gearty said. "We can't really take back the buildup of carbon dioxide (in the atmosphere) that's already happened, so it's going to keep happening for some amount of time. But it's up to us to determine how long until it'll stop."

INFORMATION:

A key driver of patients' well-being and clinical trials for Parkinson's disease (PD) is the course the disease takes over time. However, nearly all that is known about the genetics of PD is related to susceptibility -- a person's risk for developing the disease in the future. A new study by investigators from Brigham and Women's Hospital published in Nature Genetics uncovers the genetic architecture of progression and prognosis, identifying five genetic locations (loci) associated with progression. The team also developed the first risk score for predicting ...

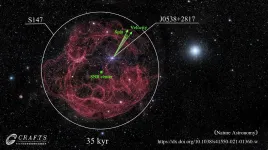

Pulsars - another name for fast-spinning neutron stars - originate from the imploded cores of massive dying stars through supernova explosion.

Now, more than 50 years after the discovery of pulsars and confirmation of their association with supernova explosions, the origin of the initial spin and velocity of pulsars is finally beginning to be understood.

Based on observations from the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST), Dr. YAO Jumei, member of a team led by Dr. LI Di from National Astronomical Observatories of Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC), found the first evidence for three-dimensional (3D) spin-velocity alignment in pulsars.

The study was published in Nature Astronomy on May 6. It also marks the beginning of in-depth pulsar research with FAST.

For decades, ...

While other medical systems across the country failed to maintain HIV screening volumes throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the University of Chicago Medicine maintained screening volumes by including universal HIV screening alongside COVID-19 testing in its busy emergency department, according to a new report published April 12 in JAMA Internal Medicine. Through targeted efforts to maintain infrastructure and enthusiasm for HIV screening, the number of HIV tests remained at pre-pandemic levels while the rate of acute HIV diagnoses actually increased.

Widespread screening to diagnose individuals newly infected with HIV is a key part of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) plan to ...

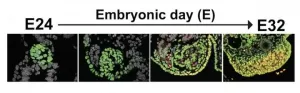

Early in human development, during the first trimester of gestation, a fetus may have XX or XY chromosomes that indicate its sex. Yet at this stage a mass of cells known as the bipotential gonad that ultimately develops into either ovaries or testes has yet to commit to its final destiny.

While researchers had studied the steps that go into the later stages of this process, little has been known about the precursors of the bipotential gonad. In a new study published in Cell Reports and co-led by Kotaro Sasaki of Penn's School of Veterinary Medicine, an international team lays ...

Although the fairy tale of the wicked stepmother is a tale as old as time, the effects of blending children with their new stepfamilies may not be as grim as once thought.

In fact, new research shows that stepparents are not at a disadvantage compared to their peers from single-parent households and actually experience better outcomes than their halfsiblings -- good news for the more than 113 million Americans that are part of a steprelationship.

Led by East Carolina University anthropologist Ryan Schacht and researchers from the University of Utah, the study, "Was Cinderella just a fairy tale? Survival differences between stepchildren and their half-siblings," is available in the May edition of the Philosophical Transactions ...

The European Alps is certainly one of the most scrutinized mountain range in the world, as it forms a true open-air laboratory showing how climate change affects biodiversity. Although many studies have independently demonstrated the impact of climate change in the Alps on either the seasonal activity (i.e. phenology) or the migration of plants and animals, no systematic analysis has been carried out on both consequences simultaneously. A European team of ecologists1, including Jonathan Lenoir, CNRS Researcher in the research unit Écologie et Dynamique des Systèmes Anthropisés (CNRS/University of Picardie Jules Verne), has just published a review that ...

Cells of all life forms are surrounded by a membrane that is made of phospholipids. One of these are the cardiolipins, which form a separate class due to their unique structure. When studying the enzyme that is responsible for producing cardiolipins in archaea (single-cell organisms that constitute a separate domain of life), biochemists at the University of Groningen made a surprising discovery. A single archaeal enzyme can produce a spectacular range of natural and non-natural cardiolipins, as well as other phospholipids. The results, which show potential for biotechnological applications, ...

Lessons Learned from India's Polio Vaccination Program Provide Valuable Insights for Future Mass Vaccination Initiatives.

Toronto - As India urgently scales up its vaccination campaign for the COVID-19 virus, a new study which examined the country's successful program to eliminate polio provides guidance on how this and future mass immunization campaigns can be successful, especially in vaccinating hard to reach groups.

The study, conducted by students and faculty with the Reach Alliance, a research initiative based at the University of Toronto's Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, says that medicine alone is insufficient for the elimination of disease.

The World Health Organization declared India polio-free in 2014. ...

AMHERST, Mass. - A team of researchers at the Center for Bioactive Delivery at the University of Massachusetts Amherst's Institute for Applied Life Sciences has engineered a nanoparticle that has the potential to revolutionize disease treatment, including for cancer. This new research, which appears today in Angewandte Chemie, combines two different approaches to more precisely and effectively deliver treatment to the specific cells affected by cancer.

Two of the most promising new treatments involve delivery of cancer-fighting drugs via biologics or antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs). Each has its own advantages and limitations. Biologics, such as protein-based ...

May 6, 2021 -- A significant level of symptoms of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress may follow COVID-19 independent of any previous psychiatric diagnoses, according to new research by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health with colleagues at Universidade Municipal de São Caetano do Sul in Brazil. Exposure to increased symptomatic levels of COVID-19 may be associated with psychiatric symptoms after the acute phase of the disease. This is the largest study to evaluate depressive, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms in tandem among patients who had mild COVID-19 ...