Study led by Penn Medicine reveals new mechanism of lung tissue regeneration

Findings could impact understanding of regenerative lung therapies and why COVID-19 and other viruses affect children differently than adults

2021-05-10

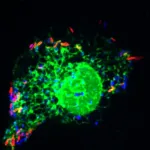

(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA-- New research performed in mice models at Penn Medicine shows, mechanistically, how the infant lung regenerates cells after injury differently than the adult lung, with alveolar type 1 (AT1) cells reprograming into alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells (two very different lung alveolar epithelial cells), promoting cell regeneration, rather than AT2 cells differentiating into AT1 cells, which is the most widely accepted mechanism in the adult lung. These study findings, published today in Cell Stem Cell, show that the long-held assumption that AT1 and AT2 cells behave the same way in children and in adults is untrue.

The lung alveolus is where gas is exchanged between the environment and blood. While scientists have known about two very different lung alveolar epithelial cells since the 1940s, there had not been much insight into them on a molecular level before now. Furthermore, these findings reveal the molecular pathway that allows for this transformation. The Penn researchers also showed that by turning off this pathway, they could reprogram adult AT1 cells into AT2 cells. This unveils a previously unappreciated level of age-dependent cell plasticity, which could explain, in part, why pediatric lungs are not as heavily impacted by COVID-19 as adult lungs, and is a major step forward in understanding lung regeneration as a form of lung therapy.

"COVID-19 has led to millions of people contracting a terrible and damaging respiratory infection, which causes severe lung injury. Some of these patients are likely to have long-term chronic lung issues, with some severe enough to need a lung transplant. We are hopeful that our research on how these alveolar cells respond to acute injury will provide new targets that could be leveraged for the development of future therapies to treat acute lung injury, and that one day we will know how to manipulate these cell pathways so that lung tissue can regenerate and heal itself, without the need for organ transplant," said the study's senior author, Edward Morrisey, PhD, the Robinette Foundation Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine and the Director of the Penn-CHOP Lung Biology Institute (LBI) in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The researchers analyzed changes in gene expression and the epigenome in mouse AT1 and AT2 cells across the lifespan. They compared these changes to those observed after acute lung injury and found that the current paradigm of how adult lungs repair themselves did not hold true for immature or mature mouse lungs.

"Scientists have long assumed that the one-way process of cell differentiation that has been well documented in the adult lung would also hold true in the infant lung, but those assumptions were overturned. We discovered that in pediatric lungs the direction of differentiation is in reverse after injury, whereas in the adult it's much more of a two-way street. In all of these contexts, it is controlled by a pathway called Hippo signaling," said the study's first author, Ian J. Penkala, a University of Pennsylvania VMD/PhD student who works in the Morrisey Lab.

In the adult lung, regeneration of the lung cells is driven by the AT2 cell population expanding and differentiating into AT1 cells. The researchers also showed that after some acute lung injuries, adult AT1 cells can robustly reprogram into AT2 cells. However, in infant mice, AT2 cells do not efficiently regenerate AT1 cells after acute lung injury. Rather, AT1 cells reprogram into AT2 cells after injury, and it is these reprogrammed AT2 cells that can ultimately proliferate after injury.

Mouse lungs are somewhat similar to human lungs in that they both have AT1 and AT2 cells, increasing the likelihood that the conclusions in this study also hold true for human lungs. Research is expanding the mechanisms that can develop future therapies for acute lung injury. Normally lungs have the ability to repair and regenerate as they are constantly exposed to pollution and microbes from the external environment. The next phase in this research would be to determine whether harnessing the Hippo pathway can help promote the lung's natural ability to regenerate after injury.

"What this discovery provides is insight into a cell pathway that we can manipulate, possibly in the future with pharmaceutical therapies. This helps us build a map of how lung cells respond, and could have major implications down the line on how we care for patients with chronic lung disease," Morrisey said.

INFORMATION:

This work was funded through grants from the BREATH Consortium of the Longfonds Foundation of the Netherlands, the Parker B. Francis Foundation, and the Ayla Gunner Prushansky Research Fund, and grants from the National Institutes of Health (F31 HL140785, K08 HL140129, R01 HL087825, R01 HL132999, and U01 HL134745).

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-10

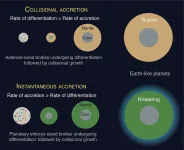

HOUSTON - (May 10, 2021) - The prospects for life on a given planet depend not only on where it forms but also how, according to Rice University scientists.

Planets like Earth that orbit within a solar system's Goldilocks zone, with conditions supporting liquid water and a rich atmosphere, are more likely to harbor life. As it turns out, how that planet came together also determines whether it captured and retained certain volatile elements and compounds, including nitrogen, carbon and water, that give rise to life.

In a study published in Nature Geoscience, Rice graduate student and lead author Damanveer Grewal and Professor Rajdeep Dasgupta show the competition between the time it takes for material to accrete into a protoplanet and the time the protoplanet ...

2021-05-10

ITHACA, N.Y. - Voyager 1 - one of two sibling NASA spacecraft launched 44 years ago and now the most distant human-made object in space - still works and zooms toward infinity.

The craft has long since zipped past the edge of the solar system through the heliopause - the solar system's border with interstellar space - into the interstellar medium. Now, its instruments have detected the constant drone of interstellar gas (plasma waves), according to Cornell University-led research published in Nature Astronomy.

Examining data slowly sent back from more than 14 billion miles away, Stella Koch Ocker, a Cornell doctoral student in astronomy, has uncovered the emission. "It's very faint and monotone, because ...

2021-05-10

Speech problems such as stammering or stuttering plague millions of people worldwide, including 3 million Americans. President Biden himself struggled with stuttering as a child and has largely overcome it with speech therapy. The cause of stuttering has long been a mystery, but researchers at Tufts University are beginning to unlock its causes and a strategy to develop potential treatments using a very curious model system - songbirds. In a study published today in Current Biology, the researchers were able to observe that a simple, reversible pharmacological treatment in zebra finches can stimulate rapid firing in a part of the brain that leads ...

2021-05-10

Numerous disease development processes are linked to epigenetic modulation. One protein involved in the process of modulation and identified as an important cancer marker is BRD4. A recent study by the research group of Giulio Superti-Furga, Principal Investigator and Scientific Director at the CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, now shows that the supply of purines as well as the purine synthesis of a cell can influence BRD4 activity and thus play a role in the carcinogenesis process. The findings were published in Nature Metabolism.

Chromatin is a ...

2021-05-10

New Curtin University research has found a bias among scientists toward colourful and visually striking plants, means they are more likely to be chosen for scientific study and benefit from subsequent conservation efforts, regardless of their ecological importance.

Co-author John Curtin Distinguished Professor Kingsley Dixon from Curtin's School of Molecular and Life Sciences was part of an international team that looked for evidence of an aesthetic bias among scientists by analysing 113 plant species found in global biodiversity hotspot the Southwestern Alps and mentioned in 280 research papers published between 1975 and 2020.

Professor Dixon said the study tested whether there was a relationship between research focus on plant species and characteristics ...

2021-05-10

In cancer, a lot of biology goes awry: Genes mutate, molecular processes change dramatically, and cells proliferate uncontrollably to form entirely new tissues that we call tumors. Multiple things go wrong at different levels, and this complexity is partly what makes cancer so difficult to research and treat.

So it stands to reason that cancer researchers focus their attention where all cancers begin: the genome. If we can understand what happens at the level of DNA, then we can perhaps one day not just treat but even prevent cancers altogether.

This drive has led a ...

2021-05-10

In the last few years, several technology companies including Google, Microsoft, and IBM, have massively invested in quantum computing systems based on microwave superconducting circuit platforms in an effort to scale them up from small research-oriented systems to commercialized computing platforms. But fulfilling the potential of quantum computers requires a significant increase in the number of qubits, the building blocks of quantum computers, which can store and manipulate quantum information.

But quantum signals can be contaminated by thermal noise generated by the movement of electrons. To prevent this, superconducting quantum systems must operate at ultra-low temperatures - less ...

2021-05-10

NEW YORK, NY (May 10, 2021)--Scientists have discovered that many esophageal cancers turn on ancient viral DNA that was embedded in our genome hundreds of millions of years ago.

"It was surprising," says Adam Bass, MD, the Herbert and Florence Irving Professor of Medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, who led the study published May 10 in Nature Genetics.

"We weren't specifically searching for the viral elements, but the finding opens up a huge new array of potential cancer targets that I think will be extremely exciting as ways to enhance immunotherapy."

Fossil ...

2021-05-10

DALLAS - May 10, 2021 - Scientists at UT Southwestern have discovered a key protein that helps the bacteria that causes Legionnaires' disease to set up house in the cells of humans and other hosts. The findings, published in Science, could offer insights into how other bacteria are able to survive inside cells, knowledge that could lead to new treatments for a wide variety of infections.

"Many infectious bacteria, from listeria to chlamydia to salmonella, use systems that allow them to dwell within their host's cells," says study leader Vincent Tagliabracci, Ph.D., assistant professor of molecular biology at UTSW and member of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center. "Better understanding the tools they use to make this happen is teaching us some interesting biochemistry and ...

2021-05-10

Many have assumed that the rates of major abdominal surgeries in adults over 65 is increasing over time as the U.S. population ages and as new technology renders surgical procedures safer for older adults. Contrary to this popular belief, a new study from the University of Chicago Medicine found the frequency of abdominal surgery in older adults is decreasing, especially among adults over the age of 85. The study, which examined data from 2002 to 2014, was published May 10 in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society.

While the research was not able to determine the exact reasons for this shift, the results indicate that improvements ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Study led by Penn Medicine reveals new mechanism of lung tissue regeneration

Findings could impact understanding of regenerative lung therapies and why COVID-19 and other viruses affect children differently than adults