In their latest research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers discovered a way to stabilize the detonation needed for hypersonic propulsion by creating a special hypersonic reaction chamber for jet engines.

"There is an intensifying international effort to develop robust propulsion systems for hypersonic and supersonic flight that would allow flight through our atmosphere at very high speeds and also allow efficient entry and exit from planetary atmospheres," says study co-author Kareem Ahmed, an associate professor in UCF's Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. "The discovery of stabilizing a detonation -- the most powerful form of intense reaction and energy release -- has the potential to revolutionize hypersonic propulsion and energy systems."

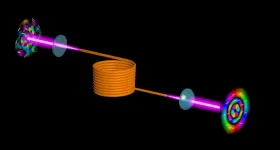

The system could allow for air travel at speeds of Mach 6 to 17, which is more than 4,600 to 13,000 miles per hour. The technology harnesses the power of an oblique detonation wave, which they formed by using an angled ramp inside the reaction chamber to create a detonation-inducing shock wave for propulsion. Unlike rotating detonation waves that spin, oblique detonation waves are stationary and stabilized.

The technology improves jet propulsion engine efficiency so that more power is generated while using less fuel than traditional propulsion engines, thus lightening the fuel load and reducing costs and emissions. In addition to faster air travel, the technology could also be used in rockets for space missions to make them lighter by requiring less fuel, travel farther and burn more cleanly.

Detonation propulsion systems have been studied for more than half a century but had not been successful due to the chemical propellants used or the ways they were mixed. Previous work by Ahmed's group overcame this problem by carefully balancing the rate of the propellants hydrogen and oxygen released into the engine to create the first experimental evidence of a rotating detonation.

However, the short duration of the detonation, often occurring for only micro or milliseconds, makes them difficult to study and impractical for use.

In the new study, however, the UCF researchers were able to sustain the duration of a detonation wave for three seconds by creating a new hypersonic reaction chamber, known as a hypersonic high-enthalpy reaction, or HyperREACT, facility. The facility contains a chamber with a 30-degree angle ramp near the propellent mixing chamber that stabilizes the oblique detonation wave.

"This is the first time a detonation has been shown to be stabilized experimentally," Ahmed says. "We are finally able to hold the detonation in space in oblique detonation form. It's almost like freezing an intense explosion in physical space."

Gabriel Goodwin, an aerospace engineer with the Naval Research Laboratory's Naval Center for Space Technology and study co-author, says their research is helping to answer many of the fundamental questions that surround oblique detonation wave engines.

Goodwin's role in the study was to use the Naval Research Laboratory's computational fluid dynamics codes to simulate the experiments performed by Ahmed's group.

"Studies such as this one are crucial to advancing our understanding of these complex phenomena and bringing us closer to developing engineering-scale systems," Goodwin says.

"This work is exciting and pushing the boundaries of both simulation and experiment," Goodwin says. "I'm honored to be a part of it."

The study's lead author is Daniel Rosato '19 '20MS, a graduate research assistant and a recipient of UCF's Presidential Doctoral Fellowship.

Rosato has been working on the project since he was an aerospace engineering undergraduate student and is responsible for experiment design, fabrication, and operation, as well as data analysis, with assistance from Mason Thorton, a study co-author and an undergraduate research assistant.

Rosato says the next steps for the research are the addition of new diagnostics and measurement tools to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomena they are studying.

"After that, we will continue exploring more experimental configurations to determine in more detail the criteria with which an oblique detonation wave can be stabilized," Rosato says.

If successful in advancing this technology, detonation-based hypersonic propulsion could be implemented into human atmospheric and space travel in the coming decades, the researchers say.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the long-term support of the Energy, Combustion and Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics Portfolio of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research in the area of detonation via grants 16RT0673/FA9550-16-1-0441 and 19RT0258/FA9550-19-0322 (Program Manager: Chiping Li), the National Science Foundation and the NASA Florida Space Grant Consortium.

Co-authors of the study included Jonathan Sosa '15 '18 '19PhD, a postdoctoral research scientist with UCF's Propulsion and Energy Research Laboratory and currently an aerospace engineer at U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, and Christian Bachman, an aerospace engineer at U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

Ahmed is an associate professor in UCF's Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, part of UCF's College of Engineering and Computer Science. He is also a faculty member of the Center for Advanced Turbomachinery and Energy Research and the Florida Center for Advanced Aero-Propulsion. He served more than three years as a senior aero/thermo engineer at Pratt & Whitney military engines working on advanced engine programs and technologies. He also served as a faculty member at Old Dominion University and Florida State University. At UCF, he is leading research in propulsion and energy with applications for power generation and gas-turbine engines, propulsion-jet engines, hypersonics and fire safety, as well as research related to supernova science and COVID-19 transmission control. He earned his doctoral degree in mechanical engineering from the State University of New York at Buffalo. He is an American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics associate fellow and a U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory and Office of Naval Research faculty fellow.

CONTACT: Robert H. Wells, Office of Research, robert.wells@ucf.edu