(Press-News.org) Woods Hole, Mass. (May 12, 2021) -- Low-to-mid latitude land surfaces at low elevation cooled on average by 5.8 ± 0.6 degrees C during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), based on an analysis of noble gases dissolved in groundwater, according to a new study published in Nature.

Temperature estimates in the study are substantially lower than indicated by some notable marine and low-elevation terrestrial studies that have relied on various proxies to reconstruct past temperatures during the LGM, a period about 20,000 years ago that represents the most recent extended period of globally stable climate that was substantially cooler than present.

"The real significance of our paper is that prior work has badly underestimated the cooling in the last glacial period, which has low-balled estimates of the Earth's climate sensitivity to greenhouse gases," said paper co-author Jeffrey Severinghaus, a professor of geosciences at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego. "The main reason that prior work was flawed was that it relied heavily on species abundances in the past. But just like humans, species tend to migrate to where the climate suits them. Think, for instance, of snowbirds moving from Canada to Arizona in winter. So, species aren't very good thermometers."

The paper does broadly support a recent marine proxy study by Tierney et al. published last year that found substantially greater low-latitude cooling than previous efforts and, in turn, suggested greater climate sensitivity than prior studies. That earlier paper suggested the equilibrium response of Earth's global-mean surface temperature is 3.4 degrees C per doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide, in line with the consensus range of estimates from state-of-the-art climate models, but somewhat higher than the usual best estimate of 3.0 degrees C.

"The rather high climate sensitivity that our results suggest is not good news regarding future global warming, which may be stronger than expected using previous best estimates. In particular, our global review reinforces the finding of several single noble gas case studies that the tropics were substantially cooler during the last glacial maximum than at present. The unpleasant implication for the future is that the warmest regions of the world are not immune to further heating," commented co-author Werner Aeschbach, a professor at the Institute of Environmental Physics, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany.

The paper made use of a technique in which measurements of noble gases dissolved in ancient groundwater enable direct and quantitative determination of past surface temperature. Noble gases in the atmosphere are chemically and biologically inactive and have no appreciable sinks or sources over the 40,000-year timescales relevant to this study. They dissolve into groundwater, and their equilibrium concentrations depend strongly on temperature. The authors compiled four decades worth of groundwater noble gas data from every continent except Antarctica, along with previously unpublished measurements from some key tropical locations to produce a global record of noble gas-derived temperatures (NGTs) of the LGM.

"Noble gas paleo temperature records are so powerful because they are based on a physical principle and are not much influenced by life--which always complicates everything-- and short term extreme events." said journal article co-author Martin Stute, a professor in the Environmental Science Department at Barnard College and an adjunct senior research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. "They provide a temperature average over hundreds to thousands of years. It is remarkable, and rewarding for me, how consistent noble gas paleo temperature reconstructions are in low latitudes from the early studies that I led in the 1990s to the most recent ones."

The study bolsters the method of analyzing noble gases to reconstruct paleo temperatures and provides more confidence in climate models, according to the authors.

"Another key goal of our study was to evaluate the overall accuracy of the so-called 'noble gas paleo-thermometer' for reconstructing temperatures on land during the last glacial period. Naturally, our ability to confidently use this tool to understand the past is related to how well it works in the present. By comparing modern temperature observations to independent estimates using noble gases in relatively young groundwater, we found that the noble gas thermometer is remarkably accurate over a wide temperature range from around 2 to 33 degrees C (36 to 91 degrees F). This adds a good deal of confidence to our estimates of cooling during the LGM," said the paper's lead author, Alan Seltzer, an assistant scientist in the Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Seltzer added that the new analysis is important because climate models "provide an important tool that policy makers can use to decide on how to prepare for future environmental changes. This study alleviates the concern that, based on LGM proxy data, models might over-predict the global mean temperature response to carbon dioxide. In fact, based on both our study and the recent marine-proxy compilation, it is becoming clear that paleoclimate proxies and models are in agreement."

INFORMATION:

About Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate an understanding of the ocean's role in the changing global environment. WHOI's pioneering discoveries stem from an ideal combination of science and engineering--one that has made it one of the most trusted and technically advanced leaders in basic and applied ocean research and exploration anywhere. WHOI is known for its multidisciplinary approach, superior ship operations, and unparalleled deep-sea robotics capabilities. We play a leading role in ocean observation and operate the most extensive suite of data-gathering platforms in the world. Top scientists, engineers, and students collaborate on more than 800 concurrent projects worldwide--both above and below the waves--pushing the boundaries of knowledge and possibility. For more information, please visit http://www.whoi.edu

Authors: Alan M. Seltzer 1*, Jessica Ng2, Werner Aeschbach3, Rolf Kipfer4,5, Justin T. Kulongoski2, Jeffrey P. Severinghaus2, and Martin Stute6,7

Affiliations:

1Marine Chemistry & Geochemistry Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA

2 Geosciences Research Division, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, CA, USA

3Institute of Environmental Physics, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany

4Department Water Resources and Drinking Water Department, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Eawag, Dübendorf, Switzerland

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) affects between one and two of every 10,000 new-born babies. This genetic disease leads to the formation of benign tumours which can massively impair the proper functioning of vital organs such as the kidneys, the liver and the brain. The disease affects different patients to varying degrees and is triggered by mutations in one of two genes, the TSC1 or TSC2 gene. An interdisciplinary team of researchers led by biochemists Prof. Daniel Kümmel and Dr. Andrea Oeckinghaus from the University of Münster (Germany) examined the "tumour suppressor protein TSC1" and, for the first time, gained insights into its hitherto unclear functions. The team identified a new mechanism, in a central cellular process, which regulates ...

University of Cincinnati researchers studied the teeth of prehistoric horses and bison in the Arctic to learn more about their diets compared to modern species.

What they found suggests the Arctic 40,000 years ago maintained a broader diversity of plants that, in turn, supported both more -- and more diverse -- big animals.

The Arctic today is spartan compared to the wildlife-rich landscape during the ice ages of the Pleistocene epoch between 12,000 and 2.6 million years ago when wild horses, mammoths, bison and other big animals roamed the steppes and grasslands of what is now northern Canada, northern Europe, Alaska and Siberia. Short-faced bears, ground sloths and even cave lions called the 49th State home.

The Arctic supported greater populations ...

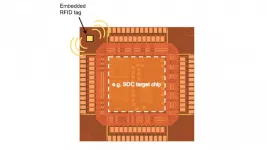

Researchers at North Carolina State University have made what is believed to be the smallest state-of-the-art RFID chip, which should drive down the cost of RFID tags. In addition, the chip's design makes it possible to embed RFID tags into high value chips, such as computer chips, boosting supply chain security for high-end technologies.

"As far as we can tell, it's the world's smallest Gen2-compatible RFID chip," says Paul Franzon, corresponding author of a paper on the work and Cirrus Logic Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at NC State.

Gen2 RFID chips are state of the art and are already in widespread use. One of the things that sets ...

Meat that is certified organic by the U.S. Department of Agriculture is less likely to be contaminated with bacteria that can sicken people, including dangerous, multidrug-resistant organisms, compared to conventionally produced meat, according to a study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The findings highlight the risk for consumers to contract foodborne illness--contaminated animal products and produce sicken tens of millions of people in the U.S. each year--and the prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms that, when they lead to illness, can complicate treatment.

The researchers found that, compared to conventionally processed meats, organic-certified meats were 56 percent less likely to be contaminated with ...

Loss of smell, or anosmia, is one of the earliest and most commonly reported symptoms of COVID-19. But the mechanisms involved had yet to be clarified. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS, Inserm, Université de Paris and the Paris Public Hospital Network (AP-HP) determined the mechanisms involved in the loss of smell in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 at different stages of the disease. They discovered that SARS-CoV-2 infects sensory neurons and causes persistent epithelial and olfactory nervous system inflammation. Furthermore, ...

Many people live with chronic pain, and in some cases, cannabis can provide relief. But the drug also can significantly impact memory and other cognitive functions. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Journal of Medicinal Chemistry have developed a peptide that, in mice, allowed Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main component of Cannabis sativa, to fight pain without the side effects.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 20% of adults in the U.S. experienced chronic pain in 2019. Opioids, the mainstay for ...

Alexandria, Va., USA -- COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in March 2020 and given an incomplete understanding of the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 at that time, the American Dental Association recommended that dental offices refrain from providing non-emergency services. As a result, 198,000 dentists in the United States closed their doors to patients. The study "Sources of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Microorganisms in Dental Aerosols," published in the Journal of Dental Research (JDR), sought to inform infection-control science by identifying the source of bacteria and viruses in aerosol generating dental procedures.

Researchers at The Ohio State University College of Dentistry, Division of Periodontology, Columbus, USA, tracked the origins of microbiota in aerosols generated during treatment ...

Are you empathic, generous and altruistic? In short, do you possess that specific personality trait defined as agreeableness in the language of psychologists? New research from SISSA recently published in the journal NeuroImage sheds light on brain mechanisms underlying this trait.

The study showed that detached and individualistic subjects seem to process information associated with social and non-social contexts in similar ways, as demonstrated by similar activation patterns in the prefrontal cortex, whereas in more agreeable subjects the activation patterns ...

Peri-implantitis, a condition where tissue and bone around dental implants becomes infected, besets roughly one-quarter of dental implant patients, and currently there's no reliable way to assess how patients will respond to treatment of this condition.

To that end, a team led by the University of Michigan School of Dentistry developed a machine learning algorithm, a form of artificial intelligence, to assess an individual patient's risk of regenerative outcomes after surgical treatments of peri-implantitis.

The algorithm is called FARDEEP, which stands for Fast and Robust Deconvolution of Expression ...

When Museums closed their doors in March 2020 for the first COVID-19 lockdown in the UK a majority moved their activities online to keep their audiences interested. Researchers from WMG, University of Warwick have worked with OUMNH, to analyse the success of the exhibitions, and say the way Museums operate will change forever.Caption: Compton Verney's homepage for the Cranach exhibition which opened in March 2020 Credit: Compton Verney

The cultural impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been analysed by researchers from WMG, University of Warwick in collaboration with OUMNH (Oxford University Museum of Natural History) who in the paper, 'Digital Responses ...