(Press-News.org) Quick: Pick your three favorite fast-food restaurants.

If you're like many people, McDonald's, Wendy's, and Burger King may come to mind--even if you much prefer In-N-Out or Chick-fil-A.

A new study from UC Berkeley's Haas School of Business and UC San Francisco's Department of Neurology found that when it comes to making choices, we surprisingly often forget about the things we like best and are swayed by what we remember. The paper, publishing this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, combines insights from economics and psychology with decision-making experiments and fMRI brain scans to examine how our imperfect memories affect our decision making.

"Life is not a multiple-choice test," says Berkeley Haas Assoc. Prof. Ming Hsu, director of UC Berkeley's Neuroeconomics Laboratory, who co-wrote the paper with Dr. Andrew Kayser, associate professor of neurology at UCSF, and lead author Zhihao Zhang, a Haas postdoctoral scholar. "Yet researchers traditionally give people a menu of options and ask them to choose."

The findings break away from traditional economic models that assume people make rational decisions from all available options. In most situations, rather than choosing from a ready-made list, we conjure choices from our memory.

"While everyone knows that human memory is limited--and there's a thriving market for reminder apps and Post-it Notes--scientists know surprisingly little about how this limit impacts our decisions," says Zhang. Answering this question could hold implications for everything from conducting consumer research and crafting public policy to managing neurodegenerative diseases.

To measure the influence of memory on decisions, the researchers examined people's choices for different types of consumer goods, such as fast food, fruit, sneakers, and salad dressing. For each, they asked one group of participants to name as many favorite brands or items in the category as they could. They asked a second group to choose their preferences from a menu of options. Based on those results, they created a mathematical method to predict which items people would choose in an open-ended situation.

The most surprising takeaway was just how often people seemed to forget to mention items they liked best, choosing less-preferred, but more easily remembered items. "A lot of people name McDonald's as their favorite, but many of those people don't actually like McDonald's as much as other brands," says Kayser. In an open-ended situation, 30% of people said McDonald's is their preferred fast food; yet for those given a list of restaurants, only half that many (15%) chose the Golden Arches, with the other half instead choosing restaurants such as In-N-Out or Chick-fil-A.

The researchers found similarly large differences between people's preferences in open ended versus list-based choices in all the other types of consumer goods tested, both branded and non-branded items, such as fruit. "The magnitude of these changes was very surprising," says Hsu. "The fact that so many people don't mention their favorites really argues against the notion that we usually act in our own best interest, as standard economic models might have us believe."

To gain a deeper scientific understanding of how memory impacts decisions, the researchers next constructed a new mathematical model that combines economic models of decision-making with psychological models of memory recall. "Very little attention has been paid to connecting these two areas," says Zhang. "By taking the best features of each, we found that we could make amazingly accurate predictions of how often people fail to choose their more preferred options due to their imperfect memories."

In fact, the predictions were so accurate that the researchers thought they had made a mistake. "We only came to trust the findings after checking and repeating the experiments multiple times," he said.

Understanding the role memory plays in decision making has implications for millions of people managing neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, says Kayser, who researches behavioral neurology.

"We know that memory declines as Alzheimer's disease progresses. We also see that decision-making capacity diminishes in areas such as financial management. But we don't yet have good models of how they might be linked, or even good ways to measure changes in decision-making capacity," he says. "For neurologists, these are urgent questions."

To nail down the role of memory retrieval in decision making, the researchers scanned the brains of a group of participants using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging). Past neuroscientific research has shown that decision-making--which involves valuation--and memory are served by different brain systems.

"When people made open-ended choices in our experiments, we saw increased activity in memory retrieval regions of the brain and enhanced communication with valuation regions," says Zhang. That didn't happen when participants simply picked choices from a list: The valuation part lit up, but memory systems showed much less activity.

This provides neural evidence for the direct involvement of memory systems in open-ended decisions, and sheds light on the nature of suboptimal decisions in these situations.

"Based on these findings, it's possible that Alzheimer's patients are particularly vulnerable when decisions are open-ended," says Kayser, "If so, this could motivate development of decision support systems that can alleviate these vulnerabilities."

The research could also provide a more targeted way of designing "nudges" that help people expand their options without mandating specific choices. For example, "If we want consumers to switch to more sustainable species of fish, it might help to find a way to get people to consider other types of seafood they may have overlooked otherwise," says Hsu.

INFORMATION:

Additional Information

Paper title: "Retrieval-Constrained Valuation: Toward Prediction of Open-Ended Decisions"

Authors: Zhihao Zhang, Shichun Wang, Maxwell Good, Siyana Hristova, Andrew Kayser & Ming Hsu

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

About the Haas School of Business: http://www.haas.berkeley.edu

About Zhihao Zhang: https://zhihao-zhang.wixsite.com/zhihao-zhang

About Ming Hsu: https://haas.berkeley.edu/faculty/hsu-ming/

About Andrew Kayser: https://profiles.ucsf.edu/andy.kayser

Autoimmune diseases have something in common with horses, bachelor's degrees and daily flossing habits: women are more likely to have them.

One reason for autoimmune diseases' prevalence in women may be sex-based differences in inflammation. In a new study, West Virginia University researcher Jonathan Busada investigated how sex hormones affect stomach inflammation in males and females. He found that androgens--or male sex hormones--may help to keep stomach inflammation in check.

"Stomach cancer is primarily caused by rampant inflammation," said Busada, an assistant professor in the School of ...

Brown bears that are more inclined to grate and rub against trees have more offspring and more mates, according to a University of Alberta study. The results suggest there might be a fitness component to the poorly understood behaviour.

"As far as we know, all bears do this dance, rubbing their back up against the trees, stomping the feet and leaving behind odours of who they are, what they are, what position they're in, and possibly whether they are related," said Mark Boyce, an ecologist in the Department of Biological Sciences.

"What we were able to show is that both males and females have more offspring if they rub, more surviving offspring if they rub and they have more mates if they rub."

The research team led by Boyce ...

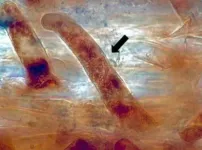

Citrus greening disease was first discovered in Florida in 2005. Since then, production of oranges in the United States for processing has declined by 72 percent between the 2007-2008 growing season and the 2017-2018 growing season, primarily in Florida. The disease was discovered in California in 2012, and now the state is beginning to see a rapid increase of citrus greening disease.

As there is currently no cure for citrus greening disease, many growers are concerned about its rapid spread and many plant pathologists are focused on learning more about the complicated nature of this disease. To add to this growing body of knowledge about citrus greening disease, a group of scientists working in California, ...

Annually, more than 350,000 children in the world are affected by pediatric cancer. Radiation has improved outcomes dramatically, but the damage caused to healthy tissue can affect the long-term health of a child. While clinicians and radiation specialists design treatments using the most up-to-date information available, there hasn't been a single guiding source of data to make evidence-based decisions that are specific for children. Now, a volunteer international research collaboration is working toward providing evidence-based guidelines for radiation therapy dosing for children. Results from this effort will help in minimizing side effects while continuing to provide ...

LA JOLLA, CA--Scientists at Scripps Research have unveiled a new Ebola virus vaccine design, which they say has several advantages over standard vaccine approaches for Ebola and related viruses that continue to threaten global health.

In the new design, described in a paper in Nature Communications, copies of the Ebola virus outer spike protein, known as the glycoprotein, are tethered to the surface of a spherical carrier particle. The resulting structure resembles the spherical appearance of common RNA viruses that infect humans--and is starkly different from the snake-like shape of the Ebola virus.

The scientists say the design is intended to stimulate a better protective immune response than standard vaccine approaches, ...

New Brunswick, N.J. (May 12, 2021) - A Rutgers study finds that symbiotic bacteria that colonize root cells may be managed to produce hardier crops that need less fertilizer.

The study appears in the journal Microorganisms.

Bacteria stimulate root hair growth in all plants that form root hairs, so the researchers examined the chemical interactions between bacteria inside root cells and the root cell.

They found that bacteria are carried in seeds and absorbed from soils, then taken into root cells where the bacteria produce ethylene, a plant growth hormone that ...

Environmental enrichment -- with infrastructure, unfamiliar odors and tastes, and toys and puzzles -- is often used in zoos, laboratories, and farms to stimulate animals and increase their wellbeing. Stimulating environments are better for mental health and cognition because they boost the growth and function of neurons and their connections, the glia cells that support and feed neurons, and blood vessels within the brain. But what are the deeper molecular mechanisms that first set in motion these large changes in neurophysiology? That's the subject of a recent study in END ...

East Hanover, NJ. May 12, 2021. A team of specialists in regenerative rehabilitation conducted a successful pilot study investigating micro-fragmented adipose tissue (MFAT) injection for rotator cuff disease in wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. They demonstrated that MFAT injection has lasting pain-relief effects. The article, "A pilot study to evaluate micro-fragmented adipose tissue injection under ultrasound guidance for the treatment of refractory rotator cuff disease in wheelchair users with spinal cord injury," (doi: 10.1080/10790268.2021.1903140) was published ahead of print on April 8, 2021, by the Journal ...

Severe symptoms of COVID-19, leading often to death, are thought to result from the patient's own acute immune response rather than from damage inflicted directly by the virus. Immense research efforts are therefore invested in figuring out how the virus manages to mount an effective invasion while throwing the immune system off course. A new study, published today in Nature, reveals a multipronged strategy that the virus employs to ensure its quick and efficient replication, while avoiding detection by the immune system. The joint labor of the research groups of Dr. Noam Stern-Ginossar at the Weizmann Institute of Science and Dr. Nir Paran and Dr. Tomer ...

New science about the fate of freshwater ecosystems released today by the journal Sustainability finds that only 17 percent of rivers globally are both free-flowing and within protected areas, leaving many of these highly-threatened systems¬--and the species that rely on them --at risk.

"Populations of freshwater species have already declined by 84 percent on average since 1970, with degradation of rivers a leading cause of this decline. As a critical food source for hundreds of millions of people, we need to reverse this trend," said Ian Harrison, freshwater specialist at Conservation International, adjunct professor ...