(Press-News.org) MISSOULA - Only an anthropologist would treasure millennia-old human feces found in dry caves.

Just ask Dr. Meradeth Snow, a University of Montana researcher and co-chair of UM's Department of Anthropology. She is part of an international team, led by the Harvard Medical School-affiliated Joslin Diabetes Center, that used human "paleofeces" to discover that ancient people had far different microorganisms living in their guts than we do in modern times.

Snow said studying the gut microbes found in the ancient fecal material may offer clues to combat diseases like diabetes that afflict people living in today's industrialized societies.

"We need to have some specific microorganisms in the right ratios for our bodies to operate effectively," Snow said. "It's a symbiotic relationship. But when we study people today - anywhere on the planet - we know that their gut microbiomes have been influenced by our modern world, either through diet, chemicals, antibiotics or a host of other things. So understanding what the gut microbiome looked like before industrialization happened helps us understand what's different in today's guts."

This new research was published May 12 in the prestigious journal Nature. The article is titled "Reconstruction of ancient microbial genomes from the human gut." Snow and UM graduate student Tre Blohm are among the 28 authors of the piece, who hail from institutions around the globe.

Snow said the feces they studied came from dry caves in Utah and northern Mexico. So what does the 1,000-year-old human excrement look like?

"The caves these paleofeces came from are known for their amazing preservation," she said. "Things that would normally degrade over time look almost brand new. So the paleofeces looked like, well, feces that are very dried out."

Snow and Blohm worked hands-on with the precious specimens, suiting up in a clean-room laboratory at UM to avoid contamination from the environment or any other microorganisms - not an easy task when the tiny creatures are literally in and on everything. They would carefully collect a small portion that allowed them to separate out the DNA from the rest of the material. Blohm then used the sequenced DNA to confirm the paleofeces came from ancient people.

The senior author of the Nature paper is Aleksandar Kostic of the Joslin Diabetes Center. In previous studies of children living in Finland and Russia, he and his partners revealed that kids living in industrialized areas - who are much more likely to develop Type 1 diabetes than those in non-industrialized areas - have very different gut microbiomes.

"We were able to identify specific microbes and microbial products that we believe hampered a proper immune education in early life," Kostic said. "And this leads later on to higher incidents of not just Type 1 diabetes, but other autoimmune and allergic diseases."

Kostic wanted to find a healthy human microbiome without the effects of modern industrialization, but he became convinced that couldn't happen with any modern living people, pointing out that even tribes in the remote Amazon are contracting COVID-19.

So that's when the researchers turned to samples collected from arid environments in the North American Southwest. The DNA from eight well-preserved ancient gut samples were compared with the DNA of 789 modern samples. Half the modern samples came from people eating diets where most food comes from grocery stores, and the remainder came from people consuming non-industrialized foods mostly grown in their own communities.

The differences between microbiome populations were striking. For instance, a bacterium known as Treponema succinifaciens wasn't in a single "industrialized" population's microbiome the team analyzed, but it was in every single one of the eight ancient microbiomes. But researchers found the ancient microbiomes did match up more closely with modern non-industrialized population's microbiomes.

The scientists found that almost 40% of the ancient microbial species had never been seen before. Kostic speculated on what caused the high genetic variability:

"In ancient cultures, the foods you're eating are very diverse and can support a more eclectic collection of microbes," Kostic said. "But as you move toward industrialization and more of a grocery-store diet, you lose a lot of nutrients that help to support a more diverse microbiome."

Moreover, the ancient microbial populations incorporated fewer genes related to antibiotic resistance. The ancient samples also featured lower numbers of genes that produce proteins that degrade the intestinal mucus layer, which then can produce inflammation that is linked with various diseases.

Snow and several coauthors and museum collection managers also led a project to ensure the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives in the research.

"This was a really vital part of the work that had to accompany this kind of research," she said. "Initially, we sent out multiple letters and emails and called the tribal historic preservation officers of the all the recognized tribes in the Southwest region. Then we met with anyone who was interested, doing short presentations and answering questions and following up with interested parties.

"The feedback we received was noteworthy, in that we needed to keep in mind that these paleofeces have to ties their ancestors, and we needed to be - and hopefully have been - as respectful as possible about them," she said.

"There is a long history of misuse of genetic data from Indigenous communities, and we strove to be mindful of this by meeting and speaking with as many people as possible to obtain their insights and perspectives. We hope that this will set a precedent for us as scientists and others working with genetic material from Indigenous communities past and present."

Snow said the research overall revealed some fascinating things.

"The biggest finding is that the gut microbiome in the past was far more diverse than today - and this loss of diversity is something we are seeing in humans around the world," she said. "It's really important that we learn more about these little microorganisms and what they do for us in our symbiotic relationships.

"In the end, it could make us all healthier."

INFORMATION:

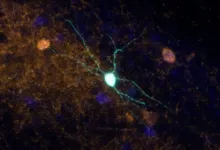

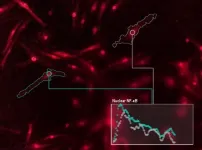

Researchers used genetic engineering tools to create a virus that can enter specific neurons and insert into the prefrontal cortex a new genetic code that induces the production of modified proteins. In tests with mice, the alteration of these proteins was sufficient to modify brain activity, indicating a potential biomarker for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and autism.

Sometimes referred to as the "executive brain", the prefrontal cortex is the region that governs higher-level cognitive functions and decision making. Studies of tissue from this brain region in patients with schizophrenia have detected alterations in two proteins: BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) and trkB (tyrosine receptor kinase B).

The relationship ...

A new study by the University of Georgia revealed that more college students change majors within the STEM pipeline than leave the career path of science, technology, engineering and mathematics altogether.

Funded by a National Institutes of Health grant and a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship and done in collaboration with the University of Wisconsin, the study examined interviews, surveys and institutional data from 1,193 students at a U.S. midwestern university for more than six years to observe a single area of the STEM pipeline: biomedical fields of study.

Out of 921 students ...

UCLA life scientists have identified six "words" that specific immune cells use to call up immune defense genes -- an important step toward understanding the language the body uses to marshal responses to threats.

In addition, they discovered that the incorrect use of two of these words can activate the wrong genes, resulting in the autoimmune disease known as Sjögren's syndrome. The research, conducted in mice, END ...

A new study from North Carolina State University finds that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from standing dead trees in coastal wetland forests - colloquially called "tree farts" - need to be accounted for when assessing the environmental impact of so-called "ghost forests."

In the study, researchers compared the quantity and type of GHG emissions from dead tree snags to emissions from the soil. While snags did not release as much as the soils, they did increase GHG emissions of the overall ecosystem by about 25 percent. Researchers say the findings show snags are important for understanding the total environmental impact of the spread of dead trees in coastal wetlands, known as ghost forests, ...

The immune system's main job is identifying things that can make us sick. In the language of immunology, this means distinguishing "self" from "non-self": The cells of our organs are self, while disease-causing bacteria and viruses are non-self.

But what about the billions of bacteria that live in our guts and provide us with benefits like digesting food and making vitamins? Are they friend or foe?

This isn't only a philosophical question. An immune system that mistakes our good gut bacteria for an enemy can cause a dangerous type of inflammation in the intestines called colitis. An immune system that looks the other way while gut microbes spill past their assigned borders is equally dangerous. Understanding ...

Our body's relationship with bacteria is complex. While infectious bacteria can cause illness, our gut is also teaming with "good" bacteria that aids nutrition and helps keep us healthy. But even the "good" can have bad effects if these bacteria end up in tissues and organs where they're not supposed to be.

Now, research published in END ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Neighborhoods without opioid treatment providers likely serve as a widespread barrier to care for those who are ready to seek help, a new study has found.

The study, led by researchers at The Ohio State University, appears today (May 12, 2021) in the journal PLOS ONE.

"The study identified clear opioid treatment deserts that undoubtedly stand in the way of access to needed care and that likely exist throughout the state and the nation. These are areas where treatment providers should be setting up shop - we need a surge of resources into these areas," said Ayaz Hyder, an assistant professor in Ohio State's College of Public Health ...

Elephant Seals' Extreme Diving Allows Them to Exploit Deep Ocean Niche

Using data captured by video cameras and smart accelerometers attached to female elephant seals, Taiki Adachi and colleagues show that the animals spend at least 80% of their day foraging for fish, feeding between 1,000 and 2,000 times per day. The unique glimpse at elephant seal foraging strategy shows how these large marine mammals exploit a unique ocean niche filled with small fish. The findings also may offer a way to monitor the health of the mesopelagic zone, the dark and cold ocean "twilight zone" ecosystem at 200 to 1,000 meters deep. Small mesopelagic fish dominate the world's ocean ...

A Johns Hopkins University-led team has created an inexpensive portable device and cellphone app to diagnose gonorrhea in less than 15 minutes and determine if a particular strain will respond to frontline antibiotics.

The invention improves on traditional testing in hospital laboratories and clinics, which typically takes up to a week to deliver results--time during which patients can unknowingly spread their infections. The team's results appear today in Science Translational Medicine.

"Our portable, inexpensive testing platform has the potential to change the game when it comes to diagnosing and enabling rapid treatment of sexually transmitted infections," said team leader Tza-Huei Wang, a professor of mechanical engineering ...

People who are genetically more likely to suffer from cardiovascular diseases may benefit from boosting a biomarker found in fish oils, a new study suggests.

In a genetic study in 1,886 Asian Indians published in PLOS ONE today (Wednesday 12 May), scientists have identified the first evidence for the role of adiponectin, an obesity-related biomarker, in the association between a genetic variation called omentin and cardiometabolic health.

The team, led by Professor Vimal Karani from the University of Reading, observed that the role of adiponectin was linked to cardiovascular disease markers that were independent of common and central obesity among the Asian Indian population. ...