(Press-News.org) Multiple studies have shown that African American women with breast cancer have lower survival rates than white women with the disease. But the association between race or ethnicity and treatment outcomes in triple-negative breast cancer -- an aggressive type of tumor that does not respond to hormonal or other targeted therapies -- has not been well defined.

Now, new research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that non-Hispanic African American women with triple-negative breast cancer also do not fare as well as non-Hispanic white women with this type of breast cancer. The study demonstrates the need for additional research to address disparities in cancer care and understand whether tumor biology or nonbiological reasons such as systemic racism -- or a combination of such factors -- may prevent African American women from receiving the same quality of care as white women.

The study appears online May 13 in JAMA Oncology.

Among women with triple-negative breast cancer, the researchers found that African Americans had a 28% increased risk of death compared with Americans of European descent, and that this disparity was at least partially due to lower rates of surgery and chemotherapy among African American patients.

"Regardless of subtypes of breast cancer, many studies have shown that African American patients have lower survival than white patients," said epidemiologist and senior author Ying Liu, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of surgery in the Division of Public Health Sciences. "But there have been conflicting studies on triple-negative breast cancer outcomes. Some of these studies have shown no disparity in survival, but these were smaller studies with fewer triple-negative or African American patients. Our research uses a large study from a national dataset demonstrating that African American patients also have lower survival for this type of breast cancer. If we want to eliminate these disparities, we must first identify what they are and work to understand what drives them."

Breast cancer is classified into categories based on whether the tumor's growth is driven by hormones such as estrogen or progesterone or by proteins such as HER2, called growth factors. Hormonal therapies that block or reduce these hormones and drugs that target HER2 can be effective in treating these tumor types. In contrast, triple-negative breast cancer continues to grow even in the absence of all these hormones and growth factors, forcing doctors and patients to rely on surgery, chemotherapy and, less often, radiation.

About 10% to 12% of all invasive breast cancer diagnoses in the U.S. are triple-negative. And for reasons that remain unclear, African American women are at higher risk of developing triple-negative breast cancer than white American women.

For the study, researchers mined a large database maintained by the National Cancer Institute that included over 23,000 women diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer from 2010 to 2015. Twenty-five percent of the patients were African American, and patients' tumors were stages 1, 2 or 3, but not stage 4, meaning they had not yet spread to other parts of the body. In a follow-up 3½ years later, 3,276 patients had died from breast cancer. The five-year survival rate was about 77% for African American women and about 83% for white women.

Compared with white patients, African American patients had 31% lower odds of receiving surgery and 11% lower odds of receiving chemotherapy. Radiation therapy is used less often for this type of cancer, but the researchers found no difference between the two groups. After adjusting for socioeconomic factors, tumor stage and size, treatment differences and other factors, the risk of death among African Americans remained increased by 16%.

Even when chemotherapy was given, there was some evidence that the treatment was less effective in African American patients. "This suggests there may be differences in tumor biology or tumor environment between African American and white patients," said Liu, also a research member of Siteman Cancer Center. "We need more research to understand if any differences exist between these tumors in their molecular biology or in their immune landscape, for example, so we can try to address them with different targeted therapies."

On average, African American patients were diagnosed at younger ages (56 years) than white patients (59 years). Tumors of African American patients also tended to be larger, diagnosed at more advanced stages and included more lymph node involvement, which is a sign the cancer is beginning to spread.

Additionally, African American patients were more likely to have health insurance through Medicaid and to live in urban areas and in counties that were more socioeconomically disadvantaged.

"There are a lot of factors beyond tumor biology that are likely contributing to these disparities," Liu said. "Our study couldn't measure many of these factors, but we know, for example, that African American patients are more likely to have unsatisfying communications with their doctors, experience discrimination in the health-care system, and have more difficulty with transportation to and from their appointments."

Curiously, researchers said the racial disparity in mortality was not found among triple-negative breast cancer patients over age 65 or those living in rural or socioeconomically poorer counties.

"Some of these associations are difficult to explain because data is limited," Liu said. "We can speculate that perhaps health care in rural or poorer communities is more difficult for cancer patients to access in general, so perhaps disparities are less apparent. But at this point, we don't know. We will need more research to understand what factors are causing these differences in treatment and survival, so that we can find ways to address them."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers R01CA215418, P30CA091842; the American Cancer Society through a Denim Days Research Scholar Grant, number RSG-18-116-01-CPHPS; the Breast Cancer Research Foundation; and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

Cho B, et al. Evaluation of racial/ethnic differences in treatment and mortality among women with triple-negative breast cancer. JAMA Oncology. May 13, 2021.

Washington University School of Medicine's 1,500 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, consistently ranking among the top medical schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

University of Massachusetts Amherst neuroscientists examining genetically identified neurons in a songbird's forebrain discovered a remarkable landscape of physiology, auditory coding and network roles that mirrored those in the brains of mammals.

The research, published May 13 in Current Biology, advances insight into the fundamental operation of complex brain circuits. It suggests that ancient cell types in the pallium - the outer regions of the brain that include cortex - most likely retained features over millions of years that are the building blocks for advanced cognition in birds and mammals.

"We as neuroscientists are catching on that birds can do sophisticated things and they have sophisticated circuits to do those things," ...

The Antarctic ice sheet was even more unstable in the past than previously thought, and at times possibly came close to collapse, new research suggests.

The findings raise concerns that, in a warmer climate, exposing the land underneath the ice sheet as it retreats will increase rainfall on Antarctica, and this could trigger processes that accelerate further ice loss.

The research is based on climate modelling and data comparisons for the Middle Miocene (13-17 million years ago) when atmospheric carbon dioxide and global temperatures reached levels similar to those expected by the end of this century.

The study was carried out by ...

A new discovery led by Princeton University could upend our understanding of how electrons behave under extreme conditions in quantum materials. The finding provides experimental evidence that this familiar building block of matter behaves as if it is made of two particles: one particle that gives the electron its negative charge and another that supplies its magnet-like property, known as spin.

"We think this is the first hard evidence of spin-charge separation," said Nai Phuan Ong, Princeton's Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics and senior author on the paper published this week in the journal Nature Physics.

The experimental results fulfill a prediction made decades ago to explain one of the most mind-bending states ...

The chemical compound glyphosate, the world's most widely used herbicide, can weaken the immune systems of insects, suggests a study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Glyphosate is the active ingredient in Round Up™, a popular U.S. brand of weed killer products.

The researchers investigated the effects of glyphosate on two evolutionarily distant insects, Galleria mellonella, the greater wax moth, and Anopheles gambiae, a mosquito that is an important transmitter of malaria to humans in Africa. They found that ...

People who work nontraditional work hours, such as 11 p.m.-7 p.m., or the "graveyard" shift, are more likely than people with traditional daytime work schedules to develop a chronic medical condition -- shift work sleep disorder -- that disrupts their sleep. According to researchers at the University of Missouri, people who develop this condition are also three times more likely to be involved in a vehicle accident.

"This discovery has many major implications, including the need to identify engineering counter-measures to help prevent these crashes from happening," said Praveen Edara, department chair and professor of civil and environmental ...

Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, a trio of science communication researchers proposes to treat the Covid-19 misinformation "infodemic" with the same methods used to halt epidemics.

"We believe the intertwining spreads of the virus and of misinformation and disinformation require an approach to counteracting deceptions and misconceptions that parallels epidemiologic models by focusing on three elements: real-time surveillance, accurate diagnosis, and rapid response," the authors write in a Perspective article.

"The word 'communicable' comes from the Latin communicare, ...

New research led by the University of Kent has found that people fail to recognise the role of factory farming in causing infectious diseases.

The study published by Appetite demonstrates that people blame wild animal trade or lack of government preparation for epidemic outbreaks as opposed to animal agriculture and global meat consumption.

Scientists forewarned about the imminence of global pandemics such as Covid-19, but humankind failed to circumvent its arrival. They had been warning for decades about the risks of intensive farming practices for public health. The scale of production and overcrowded conditions on factory farms make it easy for viruses to migrate and spread. Furthermore, ...

HOUSTON - Cytokine-activated natural killer (NK) cells derived from donated umbilical cord blood, combined with an investigational bispecific antibody targeting CD16a and CD30 known as AFM13, displayed potent anti-tumor activity against CD30+ lymphoma cells, according to a new preclinical study from researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The findings were published today in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. These results led to the launch of a Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the combination of cord blood-derived NK cells (cbNK cells) with AFM13 as an experimental cell-based immunotherapy in patients with CD30+ lymphoma.

"Developing novel NK cell therapies has been a priority for my ...

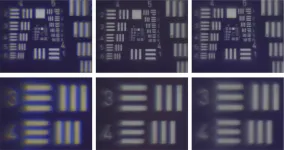

WASHINGTON -- In a new study, researchers have shown that 3D printing can be used to make highly precise and complex miniature lenses with sizes of just a few microns. The microlenses can be used to correct color distortion during imaging, enabling small and lightweight cameras that can be designed for a variety of applications.

"The ability to 3D print complex micro-optics means that they can be fabricated directly onto many different surfaces such as the CCD or CMOS chips used in digital cameras," said Michael Schmid, a member of the research team from University of Stuttgart in Germany. "The micro-optics can ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Free from human disturbance for a century, an inland island in Central America has nevertheless lost more than 25% of its native bird species since its creation as part of the Panama Canal's construction, and scientists say the losses continue.

The Barro Colorado Island extirpations show how forest fragmentation can reduce biodiversity when patches of remnant habitat lack connectivity, according to a study by researchers at Oregon State University.

Even when large remnants of forest are protected, some species still fail to survive because of subtle ...