Although the disorder affects only one in every 1,000 women who have a baby, it is much more common in mothers with a history of bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder (a condition which has symptoms of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder), or women who have suffered a previous episode of postpartum psychosis.

There are currently no biological markers that help to identify women who could go on to develop postpartum psychosis, and the role of brain connectivity - how different areas of the brain talk to each other, measured using brain scans - is yet to be fully explored.

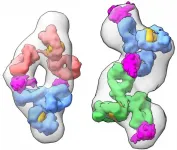

Researchers from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King's College London, and the University of Padova in Italy, found that compared with healthy women, women at risk of postpartum psychosis show altered connectivity in brain networks associated with 'goal-directed behaviour' - i.e. areas of the brain involved in planning, organising and completing short and long-term tasks.

Their study also offers the first evidence that increased connectivity within the brain's executive network (responsible for attention, working memory and decision-making) could represent a marker of resilience to postpartum psychosis relapse.

32 women 'at risk' of postpartum psychosis, and 27 healthy women, were followed up from pregnancy through to eight weeks after giving birth. They were considered 'at risk' of postpartum psychosis if they had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder, or if they had suffered a previous episode of postpartum psychosis. In the first four weeks after delivery, 15 women became unwell with symptoms indicating postpartum psychosis.

Eight weeks after giving birth, the women had brain scans while resting, followed by further scans during an emotional processing task, to study how different brain areas were activated, and the interplay between them. For the task, participants looked at images of faces expressing different emotions and had to identify that emotion (for example, a face showing a fearful expression). The researchers measured how long it took for them to successfully identify these emotions and analysed how different networks of the brain were activated.

All women at risk of postpartum psychosis, and particularly those who later became unwell, struggled more with understanding and decoding negative emotions, compared to the healthy women. This was indicated by reduced connectivity between certain brain networks during the task, and longer reaction times to the negative emotional images.

While similar connectivity changes have also been revealed in patients with other psychiatric disorders, the King's study found that these changes were more marked specifically in women who become unwell, potentially reflecting the emotional instability women experience during the course of the disorder.

Paola Dazzan, Professor of Neurobiology of Psychosis at King's College London, said: "Although rare, postpartum psychosis is a very serious mental health problem that can be really frightening for new mothers, their partners, friends and family.

"Previously, it's been difficult to spot women at risk of postpartum psychosis or explain why some are more vulnerable than others, as we really haven't known enough about the neurobiology of the illness. Our study is the first step towards a better understanding of brain connectivity as a marker of vulnerability to postpartum psychosis."

Professor Dazzan added: "We recently published another paper looking at the role of stress in postpartum psychosis, which found that higher levels of cortisol (the main stress hormone) in the third trimester of pregnancy predicted postpartum psychosis relapse. If subtle alterations in the brain's executive network, and its interaction with other brain areas, were also detectable in pregnancy, these could offer vital clues to the development of postpartum psychosis. Potentially, this could enable us to intervene earlier, allowing clinicians to provide the best possible support for new mothers, before the onset of symptoms."

The researchers are now planning to study how these brain scan changes are related to the interaction between the mothers and their babies, and also how the babies develop during their first years of life.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the Medical Research Foundation, with additional support from the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London.

Professor Paola Dazzan's postpartum psychosis research is funded by a gift in Will to the Medical Research Foundation, received in memory of a donor's sister.

Notes to editors

For further media information or a copy of the embargoed research paper, please contact Jack Stonebridge, Senior Communications Manager at the Medical Research Foundation, on jack.stonebridge@medicalresearchfoundation.org.uk or 07892762074.

Medical Research Foundation

The Medical Research Foundation is dedicated to advancing medical research, improving human health and changing people's lives.

As the charitable foundation of the Medical Research Council (MRC), we have access to some of the best medical knowledge in the world. That, along with careful governance, ensures we make an impact where it is needed most and that we use donations responsibly.

Unlike most health charities, we do not have to provide support for a particular disease or condition, or a particular research institution. We are free to choose our own research priorities, so are responsive and flexible in the way we allocate funding.

We identify research priorities according to gaps in understanding, or specific donor priorities. At the moment our research priorities are adolescent mental health (eating disorders and self-harm), drug-resistant infections, viral and autoimmune hepatitis, and pain research.

We fund and support the most promising new medical research, wherever we discover great opportunities that are not being pursued.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)

NIHR is the nation's largest funder of health and care research. The NIHR:

Funds, supports and delivers high quality research that benefits the NHS, public health and social care

Engages and involves patients, carers and the public in order to improve the reach, quality and impact of research

Attracts, trains and supports the best researchers to tackle the complex health and care challenges of the future

Invests in world-class infrastructure and a skilled delivery workforce to translate discoveries into improved treatments and services

Partners with other public funders, charities and industry to maximise the value of research to patients and the economy

The NIHR was established in 2006 to improve the health and wealth of the nation through research, and is funded by the Department of Health and Social Care. In addition to its national role, the NIHR supports applied health research for the direct and primary benefit of people in low- and middle-income countries, using UK aid from the UK government.

King's College London

King's College London is one of the top 10 UK universities in the world (QS World University Rankings, 2020) and among the oldest in England. King's has more than 31,000 students (including more than 12,800 postgraduates) from some 150 countries worldwide, and some 8,500 staff.

King's has an outstanding reputation for world-class teaching and cutting-edge research. In the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF), eighty-four per cent of research at King's was deemed 'world-leading' or 'internationally excellent' (3* and 4*).

King's Strategic Vision looks forward to our 200th anniversary in 2029. It shows how King's will make the world a better place by focusing on five key strategic priorities: educate to inspire and improve; research to inform and innovate; serve to shape and transform; a civic university at the heart of London; an international community that serves the world.

More information: http://www.kcl.ac.uk/aboutkings/facts/index