Grape genetics research reveals what makes the perfect flower

2021-05-18

(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. - Wines and table grapes exist thanks to a genetic exchange so rare that it's only happened twice in nature in the last 6 million years. And since the domestication of the grapevine 8,000 years ago, breeding has continued to be a gamble.

When today's growers cultivate new varieties - trying to produce better-tasting and more disease-resistant grapes - it takes two to four years for breeders to learn whether they have the genetic ingredients for the perfect flower.

Females set fruit, but produce sterile pollen. Males have stamens for pollen, but lack fruit. The perfect flower, however, carries both sex genes and can self-pollinate. These hermaphroditic varieties generally yield bigger and better-tasting berry clusters, and they're the ones researchers use for additional cross-breeding.

Now, Cornell University scientists have worked with the University of California, Davis, to identify the DNA markers that determine grape flower sex. In the process, they also pinpointed the genetic origins of the perfect flower. Their paper, "Multiple Independent Recombinations Led to Hermaphroditism in Grapevine," published April 13 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

"This is the first genomic evidence that grapevine flower sex has multiple independent origins," said Jason Londo, corresponding author on the paper and a research geneticist in the USDA-Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) Grape Genetics Unit, located at Cornell AgriTech. Londo is also an adjunct associate professor of horticulture in the School of Integrative Plant Science (SIPS), part of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

"This study is important to breeding and production because we designed genetic markers to tell you what exact flower sex signature every vine has," Londo said, "so breeders can choose to keep only the combinations they want for the future."

Today, most cultivated grapevines are hermaphroditic, whereas all wild members of the Vitis genus have only male or female flowers. As breeders try to incorporate disease-resistance genes from wild species into new breeding lines, the ability to screen seedlings for flower sex has become increasingly important. And since grape sex can't be determined from seeds alone, breeders spend a lot of time and resources raising vines, only to discard them several years down the line upon learning they're single-sex varieties.

In the study, the team examined the DNA sequences of hundreds of wild and domesticated grapevine genomes to identify the unique sex-determining regions for male, female and hermaphroditic species. They traced the existing hermaphroditic DNA back to two separate recombination events, occurring somewhere between 6 million and 8,000 years ago.

Londo theorizes that ancient viticulturists stumbled upon these high yielding vines and collected seeds or cuttings for their own needs - freezing the hermaphroditic flower trait in domesticated grapevines that are used today.

Many wine grapes can be traced back to either the first or second event gene pool. Cultivars such as cabernet franc, cabernet sauvignon, merlot and Thompson seedless are all from the first gene pool. The pinot family, sauvignon blanc and gamay noir originate from the second gene pool.

What makes chardonnay and riesling unique is that they carry genes from both events. Londo said this indicates that ancient viticulturalists crossed grapes between the two gene pools, which created some of today's most important cultivars.

Documenting the genetic markers for identifying male, female and perfect flower types will ultimately help speed cultivar development and reduce the costs of breeding programs.

"The more grape DNA markers are identified, the more breeders can advance the wine and grape industry," said Bruce Reisch, co-author and professor in both the Horticulture and the Plant Breeding and Genetics sections of SIPS. "Modern genetic sequencing technologies and multi-institutional research collaborations are key to making better grapes available to growers."

INFORMATION:

Funding for this study was provided by a Specialty Crop Research Initiative Competitive Grant from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Co-authors on the paper also include Cheng Zou and Qi Sun at the Cornell Institute of Biotechnology; Melánie Massonnet, Andrea Minio and Dario Cantu at UC Davis; Lance Cadle-Davidson at the USDA-ARS Grape Genetics Unit; Victor Llaca at Corteva Agriscience; Avinash Karn and Fred Gouker in the Horticulture Section of SIPS; and Sagar Patel and Anne Fennell of South Dakota State University.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-18

Due to climate change, the average global temperature will rise in the coming decades. This should also significantly increase the number of so-called cooling degree days. These measure the number of hours, in which the ambient temperature is above a certain threshold, at which a building must be cooled to keep the indoor temperature at a comfortable level. The rising values may lead to an increased installation of AC systems in households. This could lead to a higher energy demand for cooling buildings, which is already expected to increase due to climate change and population growth.

Nip-and-tuck ...

2021-05-18

Scientists have long thought that there was a direct connection between the rise in atmospheric oxygen, which started with the Great Oxygenation Event 2.5 billion years ago, and the rise of large, complex multicellular organisms.

That theory, the "Oxygen Control Hypothesis," suggests that the size of these early multicellular organisms was limited by the depth to which oxygen could diffuse into their bodies. The hypothesis makes a simple prediction that has been highly influential within both evolutionary biology and geosciences: Greater atmospheric oxygen should always increase the size to which multicellular organisms can grow. ...

2021-05-18

When a person views a familiar image, even having seen it just once before for a few seconds, something unique happens in the human brain.

Until recently, neuroscientists believed that vigorous activity in a visual part of the brain called the inferotemporal (IT) cortex meant the person was looking at something novel, like the face of a stranger or a never-before-seen painting. Less IT cortex activity, on the other hand, indicated familiarity.

But something about that theory, called repetition suppression, didn't hold up for University of Pennsylvania neuroscientist Nicole Rust. "Different images produce different amounts of activation even when they are all novel," says ...

2021-05-18

The combination of a carb-heavy diet and poor oral hygiene can leave children with early childhood caries (ECC), a severe form of dental decay that can have a lasting impact on their oral and overall health.

A few years ago, scientists from Penn's School of Dental Medicine found that the dental plaque that gives rise to ECC is composed of both a bacterial species, Streptococcus mutans, and a fungus, Candida albicans. The two form a sticky symbiosis, known scientifically as a biofilm, that becomes extremely virulent and difficult to displace from the tooth surface.

Now, a new study from the group offers a strategy for disrupting this biofilm by targeting the yeast-bacterial interactions ...

2021-05-18

In studying COVID-19 testing and positivity rates in West Virginia between March and September 2020, West Virginia University researchers found disparities among Black residents and residents experiencing food insecurity.

Specifically, the researchers found communities with a higher Black population had testing rates six times lower than the state average, which they argue could potentially obscure prevalence estimates. They also found that areas associated with food insecurity had higher levels of testing and a higher rate of positivity.

"This could mean that public health officials are targeting predominately rural areas to keep tabs on how the pandemic will unfold in isolated communities within higher food insecurity," said Brian Hendricks, a research assistant professor with ...

2021-05-18

Australian scientists have compared an ancient Greek technique of memorising data to an even older technique from Aboriginal culture, using students in a rural medical school.

The study found that students using a technique called memory palace in which students memorised facts by placinthem into a memory blueprint of the childhood home, allowing them to revisit certain rooms to recapture that data. Another group of students were taught a technique developed by Australian Aboriginal people over more than 50,000 years of living in a custodial relationship with the Australian land.

The ...

2021-05-18

Researchers at Michigan Medicine found that people with venom allergies are much more likely to suffer mastocytosis, a bone marrow disorder that causes higher risk of fatal reactions.

The team of allergists examined approximately 27 million United States patients through an insurance database - easily becoming the nation's largest study of allergies to bee and wasp stings, or hymenoptera venom. The results, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, revealed mastocytosis in fewer than 0.1% of venom allergy patients - still near 10 times higher than those without allergies.

"Even though there is mounting interest, mast cell diseases are quite understudied; ...

2021-05-18

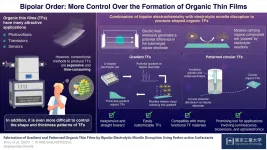

Modern and emerging applications in various fields have found creative uses for organic thin films (TFs); some prominent examples include sensors, photovoltaic systems, transistors, and optoelectronics. However, the methods currently available for producing TFs, such as chemical vapor deposition, are expensive and time-consuming, and often require highly controlled conditions. As one would expect, making TFs with specific shapes or thickness distributions is even more challenging. Because unlocking this customizability could spur advances in many sophisticated applications, researchers are actively exploring new approaches for ...

2021-05-18

In quiet moments, the brain likes to wander—to the events of tomorrow, an unpaid bill, an upcoming vacation.

Despite little external stimulation in these instances, a part of the brain called the default mode network (DMN) is hard at work. "These regions seem to be active when people aren't asked to do anything in particular, as opposed to being asked to do something cognitively," says Penn neuroscientist Joseph Kable.

Though the field has long suspected that this neural network plays a role in imagining the future, precisely how it works hadn't been fully understood. Now, research from Kable and two former graduate students in his lab, Trishala Parthasarathi, associate director of scientific services at OrtleyBio, and Sangil Lee, a postdoc at University of California, ...

2021-05-18

SAN DIEGO (May TK, 2021) - Compared to most other bear species, very little is known about how female Andean bears choose where they give birth to cubs. As a critical component of the reproductive cycle, birthing dens are essential to the survival of South America's only bear species, listed as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

A new study led by Russ Van Horn, Ph.D., published April in the journal Ursus, takes the most detailed look yet at the dens of this species. Van Horn, a population sustainability scientist, leads San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance's Andean bear conservation program. He was joined by colleagues from the University of British Columbia's Department of Forest ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Grape genetics research reveals what makes the perfect flower